Political instability, poor infrastructure and low education rates in some countries are putting off investments. But without money it is hard for countries to catch up, writes Kauê Lopes dos Santos.

At the beginning of the 21st century, there was widespread optimism about Africa’s economic performance. High growth rates of Gross Domestic Product – at an average of 4.6 per cent between 2001 and 2019 – paved the way for what the Malawian economist Thandika Mkandawire called “Afro-Euphoria.”

Those countries that demonstrated political stability alongside the economic growth earned the moniker “economic lions”, in a clear allusion to the Asian Tigers of the 1990s. This combination of stability and growth attracted the interest of international capital in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI). Countries such as Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, and South Africa took advantage of this favourable situation to stimulate segments of their economies and became the priority destinations for FDI on the continent.

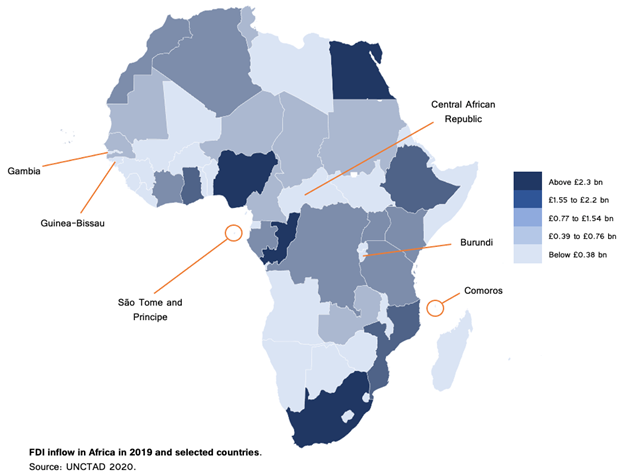

This type of investment is particularly important as it creates stable and lasting links between countries helping them integrate into the global economy. Looking at a map of the distribution of FDI across Africa it is clearly uneven. To help drive economic development in Africa it is vital to know what is behind the uneven distribution of FDI across Africa.

The uneven map

The uneven distribution of capital across space is nothing new. In the case of FDI, this inequality occurs on a global scale. According to UNCTAD, in 2019, Africa absorbed 2.9 per cent of global FDI (£35.4 billion), while Asia absorbed 30.8 per cent (£369.5 billion) and Latin America and the Caribbean 10.7 per cent (£128.0 billion). Despite the low percentage, this was the first time Africa had received more than £7.7 billion in a single year.

In 2019, FDI flows were concentrated in five countries: Egypt (£7.0 billion), South Africa (£3.5 billion), Congo (£2.6 billion), Nigeria (£2.5 billion) and Ethiopia (£1.9 billion). A more favourable environment for investments – related to the efficiency of infrastructure, a more qualified labour market, a more consolidated consumer market and relative political stability – helps to understand the direction of FDI to these countries.

Most of the countries on the continent received less than £300 million of FDI. Among them, six stand out as those that received the least investments: Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, the Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe, received less than £30 million in 2019.

Forgotten economies

There is not a single factor that explains a country being forgotten by FDI. Political, demographic, and infrastructure issues all play a part.

Although there is a trend towards democratisation on the African continent, among the countries at the bottom of the FDI league table, only The Gambia is actively becoming more democratic and is home to political pluralism, elections, and globally respected press freedom. Guinea-Bissau, Sao Tome and Principe, Burundi, and Comoros are examples of hybrid regimes marked by limited political pluralism, systematic political repression, and impeded rule of law. The Central African Republic is facing civil conflicts.

Demographically, the correlation between the African population and the attraction of FDI is manifested through the quality and cost of its workforce and the purchasing power and potential of its consumer market.

The overall populations of the countries with low levels of FDI are diverse: from 200 thousand in São Tomé and Príncipe to 11.8 million in Burundi. But there are other factors where there are similarities.

The forgotten territories’ populations all suffer from precarious access to education. This negatively affects the quality of the national workforce and has other knock-on effects. A significant part of the population of the selected countries lives in poverty: 79.4 per cent in CAR, 74.3 per cent in Burundi, 67.3 per cent in Guinea-Bissau, 41.6 per cent in the Gambia, 37.3 per cent in Comoros and 22.1 per cent in São Tomé and Príncipe. This leads to lower purchasing power of the population, which ends up reducing the interest of many investments aimed at the medium and long term.

Access to transport, energy, and telecoms infrastructure plays a significant role in the attraction of FDI. The countries with low FDI are highly dependent on precarious roads and none have operational railways. Except for Comoros, paved roads are at a premium. Only 17.4 per cent in the Gambia, 12.1 per cent in Burundi, 10.2 per cent in Guinea-Bissau, and 2.9 per cent in CAR of the road network is paved. Maritime or dry ports are also fundamental to the movement of goods. Being landlocked countries, Burundi and CAR have ports on rivers and lakes but still depend on seaports in Tanzania and Cameroon.

All the countries highlighted struggle with one or all of the political, demographic, and infrastructural variables that appeal to FDI.

The uneven distribution of FDI on the African continent explains how international capital requires a set of variables for its spatial allocation. The forgotten territories in Africa are those where the articulation between political stability, transport infrastructure and the labour market create an environment that is not very attractive for investments. To enter the universe of Afro-euphoria, countries must develop a strategy to promote political stability and the modernisation of their productive forces.

Photo credit: Pexels

A great insight into the nuances of economies across Africa.

I don’t foresee Africa developing any time soon due to wanton corruption by the political class and a lack of investment in critical sectors. In Ghana, one has to pay heavily in order to be recruited even into the public sector. Qualified candidates have their skills rotting away and unskilled people in work they don’t qualify. Our governments take loans and use them to pay politicians.