The peace agreement between Ethiopia and the Oromo Liberation Front was doomed to failure, writes Marew Abebe Salemot.

When Abiy Ahmed became prime minister of Ethiopia the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) was delisted from the national terrorist database. The group later announced a unilateral ceasefire and on 7 August 2018, signed a peace agreement with the Ethiopian state in the Eritrean capital Asmara to end hostilities. However, the Asmara peace agreement fell apart less than five months later. Five years after this failure two rounds of peace talks in May and November have concluded without agreement. There are several reasons why peace negotiations between the OLF and Ethiopia have been futile.

The lack of an agreed document

The 2018 Asmara peace agreement was reached without a written signed accord. In August 2018, the OLF leadership declared a unilateral ceasefire in response to Prime Minister Abiy’s request for dialogue with armed groups. Later, on 7 August 2018, OLF and Ethiopia reached a peace agreement in Asmara to halt hostilities and restore peace and stability.

The Asmara peace deal, however, was short-lived, allegations and counteraccusations erupted, and OLF later resumed its armed struggle. Soon after, debates ensued regarding what exactly had been agreed upon between OLF and Ethiopia and it was unclear who – the Ethiopian government, OLF or both – failed to meet the terms of the agreement as it was not publicly available. The absence of a signed peace agreement made the post-peace deal environment more volatile and subject to claims and counterclaims.

A collapsed state

Following the 2018 Asmara peace agreement, the internal political intricacies of Ethiopia drastically deteriorated. The democratic reform and euphoria brought by Abiy Ahmed which included him winning the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize soon became a kind of ironic memory.

One of the major factors that exacerbated Ethiopian instability in the period post the peace agreement was the unconstitutional election postponement, partly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The government’s decision to delay the election was considered a power grab and an unconstitutional term extension and was rejected by most opposition parties including OLF.

Ethiopia has since descended into civil war with ethnically motivated killings, religious conflict, and displacement as common trends throughout the country. These constraints weaken the Ethiopian government’s capabilities to successfully implement any peace agreement.

Multiple warring parties

The precarious nature of the Asmara peace agreement implementation increased when the OLF fractured.

The existence of multiple factions and splinter groups within OLF – formed before and after the 2018 Asmara peace agreement – have disrupted the implementation environments. From 1974 until 2018, OLF fragmented into several groups, including the Oromo Democratic Front, the OLF-Transition Authority, the United Front for the Liberation of Oromia and the United-OLF. Settlement of disputes is a lengthy and careful procedure that will need to consider the fundamental causes of the opposing parties’ incompatibility.

The 2018 Asmara peace accord was signed only a week after OLF declared a unilateral ceasefire, leaving insufficient time to negotiate the separate stages of a peace agreement (pre-negotiations, substantive agreements and implementation) with the various factions of OLF. Those who lost faith in the negotiation process shortly after the 2018 agreement formed factions including the Oromo Liberation Army and Oromo Liberation Front Shene Group and vowed not to relinquish the use of weapons.

Demands for secession

OLF has long held a liberation struggle with the goal of forming a new Oromia state, belonging to Oromos who are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia.

OLF claims that the Oromo people and their land Oromia were ‘colonized’ by the Abyssinians in the late 19th to the early 20th century. The ‘colonialism’ thesis has been used to identify the OLF as a political liberation movement.

The current Ethiopian constitution (Article 39) sets secession as an unconditional right to any ethnic group in the country. The 2018 Asmara peace agreement, however, did not address such fundamental questions and potentially affected the post-peace deal implementation settings.

The presence of spoilers

The first signs of failure came in September 2018, when more than 60 ethnic Gamo civilians were killed in Burau (Oromia region) on the outskirts of western Addis Ababa. This came just a day after OLF leader Dawud Ibsa returned from abroad. This alarmed many Ethiopians because it occurred shortly after the agreement was made.

Later, Hachalu Hundessa, an Oromo popular singer, was assassinated in Addis Ababa and the government announced that the assassin was part of OLF’s anti-government plot and this heightened the tension between OLF and the Ethiopian government. On 23 June 2018, there was also an assassination attempt targeting Abiy Ahmed while he waved to thousands of supporters in Addis Ababa.

The Asmara peace agreement was also botched when OLF established a military alliance with the Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF) to topple PM Abiy Ahmed’s government during the Tigray war between 2020-2022 before the TPLF and the Ethiopian government agreed their own peace agreement in Pretoria.

Hostile neighbouring states and networks

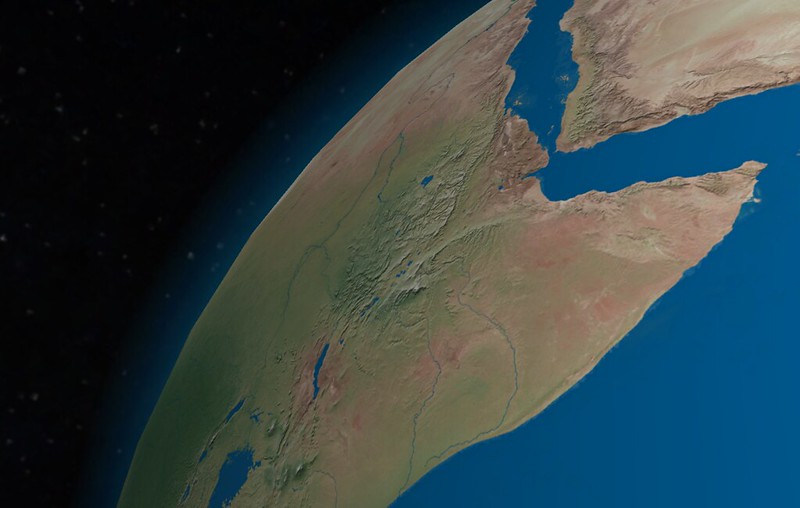

The presence of hostile neighbouring states which harbor OLF, and its combatants contributed to the failure of the 2018 peace agreement between OLF and Ethiopia. Until 2019 the rebels were stationed in neighboring countries, mainly in Eritrea and Sudan. Ethiopia’s location in the Horn of Africa, a conflict-ridden region including where Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, and South Sudan exposes the country to instability.

These fragile countries have been a safe ‘haven’ for rebel groups, human trafficking, illicit trade and unregulated transactions of small arms and light weapons. At different times OLF has its physical address in Djibouti, Somalia, Eritrea, Egypt, and Sudan and has used these neighboring counties as springboards to continue its armed struggle against successive Ethiopian governments.

A lasting peace can only be achieved when conflicting parties are willing to address the fundamental problems that trigger Ethiopia´s seemingly insurmountable political challenges.

Photo credit: GovernmentZA used with permission CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED

A settlement needs a willingness to compromise..yes COMPROMISE.

Ethiopia will never be a genuine multi party democracy until groups learn to compromise!!