by Dr Kate Laffan

The landmark report released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in October 2018 emphasised the need for a widespread shift towards more sustainable lifestyles if we are to limit global warming to the 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and avoid the catastrophic consequences that warming beyond that level is expected to entail.

The pro-environmental actions involved in such a lifestyle shift, such as recycling and buying green energy, have traditionally been conceptualised as altruistic behaviours, where altruism is understood as prioritising the wellbeing of others independent of one’s own. The time and money costs associated with such activities, as well as the inconvenience and discomfort they can involve, are often cited as evidence of the sacrificial nature of these actions. This negative view of pro-environmental behaviour (PEB) likely acts as a barrier to the adoption of sustainable lifestyles as it frames these actions in terms of losses – something research in behavioural economics tells us individuals are highly motivated to avoid.

In recent years, however, research has begun to explore the relationship between engaging in PEB and individuals’ subjective wellbeing – people’s reports of how they think about their lives and feel as they go about them. Emerging evidence in this area suggests that that people do not necessarily lose out by engaging in PEB and that there may even be psychological benefits available from going green.

A small body of literature suggests that individuals who engage in lifestyles based on voluntary simplicity (i.e. freely choosing to live frugally) report higher levels of life satisfaction, while those that hold materialistic values tend to have lower wellbeing. Additionally, a number of studies which have looked specifically at the relationship between SWB and PEBs find that doing good in this domain is linked to feeling good about life. These works find that people who purchase green products, recycle, save water and energy and volunteer for green causes all have higher levels of life satisfaction than their less environmentally friendly counterparts.

My own research in this area has gone beyond single measures of PEB and life satisfaction and has investigated the relationship between a series of PEBs and a range of SWB measures. The results of this work suggest that the more PEBs an individual engages in the more worthwhile they consider their activities to be – a eudemonic measure of SWB which is linked to individuals’ needs for feelings of purpose, autonomy and competence. This work also finds that individuals who engage in PEB report being no happier or more anxious day-to-day, suggesting that individuals do not derive pleasure from engaging in PEB, but importantly, that these behaviours do not come at a hedonic cost.

Other recent work in this area has begun to explore the mechanisms behind these relationships and has documented evidence which suggests that positive green self-image, opportunities to socialize and conformity with social norms all play a role. The next step in this literature is to go beyond presenting associations between individuals’ PEB engagement and SWB to produce causal evidence as to whether engaging in PEB directly enhances people’s wellbeing and if so why.

Understanding the wellbeing effects of PEB will inform both how it is conceptualised and the strategies used to promote it. The traditional view of PEB as a sacrifice gives rise to intervention strategies centred around making moral appeals which highlight the impact of environmental issues on others and/or on the planet. While there is some evidence that these approaches can be effective in some situations, a number of authors have cautioned against them, suggesting that by emphasising sacrifice rather than wellbeing enhancing solutions, the altruism centred approach contributes to feelings of helplessness and excludes self-interested individuals from PEB.

The results of the current work suggest alternative strategies to encourage PEB including making salient the potential wellbeing benefits of engaging in PEB and targeting factors such social norms and people’s green self-image which are thought to be behind the positive PEB-SWB relationship. We are not yet at a point where we can definitively say that such strategies will successfully promote both PEB and individual wellbeing, but the results of the aforementioned work highlight that there may be environmental and psychological win-wins on the table when we are considering whether to make the essential lifestyles changes necessary to protect our natural environment.

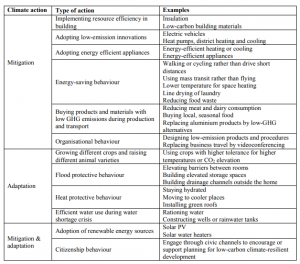

Want to know where to get started? The IPPC report provides the following list of mitigation and adaptation behaviours relevant for 1.5ºC. (For further details see Chapter 4 of the IPCC report)

Editor’s Note:This blog is linked to a new paper “Well-being in metrics and policy” published in Science and a blog by Dr Laffan’s co-authors “Progress paradoxes in China, India and the USA: A tale of growing but unhappy countries“.