The European economy is experiencing a severe economic contraction as a result of the coronavirus lockdowns in place across most countries. We invited our European panel to express their views on Europe’s economic policy response to the Covid-19 crisis: first, on whether the economic benefits from lockdowns are likely to outweigh their costs over the medium term; and second, on the desirability of a pan-Eurozone fiscal policy response to supplement national measures, including the possibility of issuing new pooled debt instruments – known as ‘coronabonds’ – to fund government spending.

We asked the experts whether they agreed or disagreed with the following three statements, and, if so, how strongly and with what degree of confidence.

The impact of public health measures on the economy

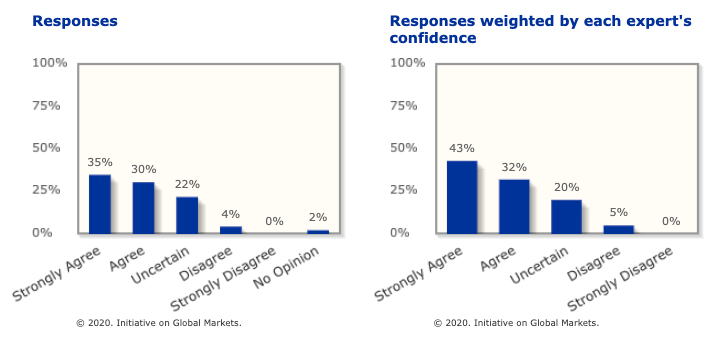

A. Severe lockdowns – including closing non-essential businesses and strict limitations on people’s movement – are likely to be better for the economy in the medium term than less aggressive measures.

Source: European IGM Economic Experts Panel

On the first statement, weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, 43% of the panel strongly agree, 32% agree, 20% are uncertain, and 5% disagree.

Among the comments of the three quarters of the panelists who agree or strongly agree, Xavier Freixas of Universitat Pompeu Fabra notes: ‘Hospital capacity is limited and the economic value of life in Europe is high.’ Jean-Pierre Danthine of the Paris School of Economics says: ‘I agree wherever there is limited availability of infection tests and restriction in tracing the contagion (Europe today).’

Others comment on the need for testing. Karl Whelan of University College Dublin remarks: ‘Economic activity will return closer to normality when there is extensive testing and tracing. Lockdowns give time to develop this.’ Christopher Pissarides of the London School of Economics adds: ‘Lockdown should be able to get rid of the disease in the medium term. Less severe measures cannot unless they are accompanied by mass tests.’

Several experts point out the likely impact of less aggressive measures on the workforce. Costas Meghir at Yale warns: ‘Mass sickness will not only disable many workers but will also reduce confidence and increase uncertainty.’ Peter Neary at Oxford emphasises: ‘The alternative to lockdowns is not a return to “normal” but many people unwilling to work even though allowed to, and soaring death rates.’ And Marco Pagano at Università di Napoli Federico II argues: ‘The faster you contain and eliminate contagion, the faster people can go back to work. If you do not, people will simply not go back to work.’

Christian Leuz at Chicago Booth notes: ‘Several studies suggesting that strict measures have economic benefits of lives saved that outweigh value of projected losses of GDP.’ He points to US evidence on the net benefits of social distancing; similar evidence for Italy’s Lombardy; a study of the likely economic impact of Covid-19 under different disease scenarios; and the widely discussed piece on ‘Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance’.

Of the experts who say that they are uncertain, two mention alternatives to severe lockdowns. Hélène Rey at London Business School notes: ‘It depends on the accompanying measures of a partial lockdown (testing and tracking, see Singapore)’; and Jan Eeckhout at University College London suggests: ‘Testing and tracing as in South Korea might be better than severe lockdown.’ Charles Wyplosz of the Graduate Institute, Geneva, who agrees with the statement, also points to possible lessons from different approaches: ‘Ceteris paribus, but large-scale testing and selective isolation may be better. Watch out for the Swedish experiment too.’

Desirability of a joint euro area fiscal response

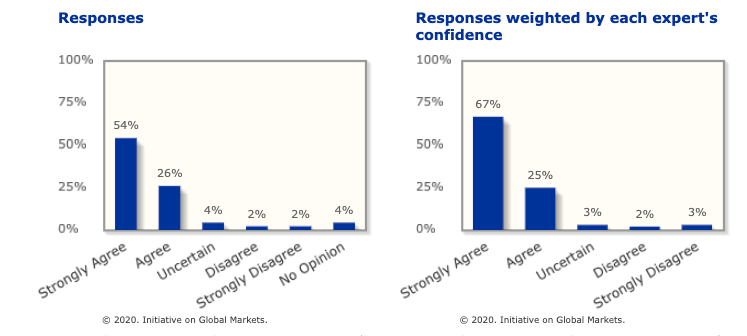

B. While national governments have responded to the crisis with substantial economic policy measures, a joint euro area fiscal response is still highly desirable.

Source: European IGM Economic Experts Panel

On the second statement about the desirability of a pan-Eurozone fiscal policy response to supplement national measures, there is a very broad consensus in agreement. Again weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response, 67% of the panel strongly agree, 25% agree; 3% are uncertain, 2% disagree, and 3% strongly disagree.

In comments, Jan Pieter Krahnen of Goethe University Frankfurt is concerned that: ‘Without a coordinated European answer, the crisis may spill into the banking sector, and also to sovereign risk – endangering the Eurozone.’ Costas Meghir adds: ‘A common currency area can only be sustained in the long run if the absence of country-level monetary policy is replaced by mutual insurance.’

Patrick Honohan of Trinity College Dublin is one of three experts who ask: ‘If not now, when?’, adding: ‘Common shock, potentially divergent consequences including externalities.’ Hélène Rey too notes the nature of the shock: ‘Massive symmetric shock, some countries constrained by lack of fiscal space.’

Christopher Pissarides comments: ‘As in dealing with other crises, coordinated fiscal policy is better for the group as a whole than independent policies.’ Peter Neary takes a similar view: ‘Common monetary policy combined with unlinked national fiscal policies has never made sense. In a crisis, its problems are even greater.’

Others, while agreeing with the statement, are more cautious about joint action. Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institute says: ‘Desirable yes, highly perhaps not: can go a long way with just domestic fiscal policies.’ Charles Wyplosz states: ‘A selective response. Need to allow all governments to run large temporary deficits. Coordination of targeted fiscal measures is illusory.’

Christian Leuz concludes: ‘Coordination of response very desirable; not clear more is needed right now, but solidarity is important and opportunity to show EU matters.’ He links to a warning of the coronavirus threat to the European Union, and a proposal for cooperation on a Covid credit line in the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) – both by IGM panelists.

Coronabonds

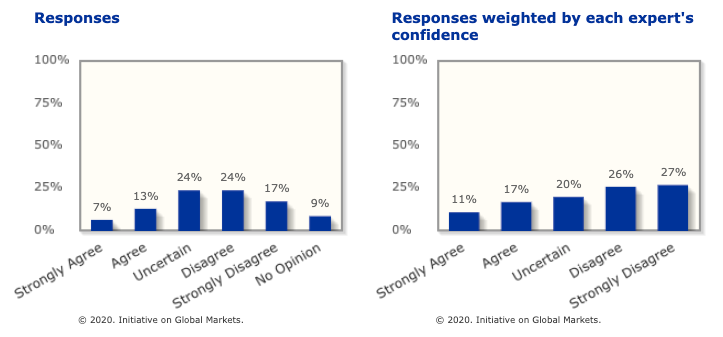

C. Given the willingness of the European Central Bank to buy sovereign bonds, including Italian bonds, without limits, there is no need for ‘coronabonds’.

Source: European IGM Economic Experts Panel

On the third statement, asking whether there is no need for new pooled debt instruments to fund government spending given the willingness of the European Central Bank (ECB) to buy sovereign bonds without limits (again weighted by each expert’s confidence in their response), 11% of the panel strongly agree, 17% agree, 20% are uncertain, 26% disagree, and 27% strongly disagree.

The lack of a strong consensus is reflected in the experts’ comments. Among the small majority who disagree with the statement, some, like Agnès Bénassy-Quéré of the Paris School of Economics, point out that ‘Relying entirely on the ECB is dangerous’. She adds: ‘The ECB would also have to roll over its holding over a long period, and face legal and political problems.’ Karl Whelan says: ‘ECB secondary market purchases won’t stop concerns about sovereign default. Questions also about the extent of credit losses ECB could take.’

Focusing specifically on Italy, Jean-Pierre Danthine worries: ‘A special treatment of Italy will create severe tensions if there cannot be ex-ante agreement on a mutualised solution.’ And Marco Pagano notes that: ‘Despite the ECB bond purchases, servicing Italian public debt is more expensive than servicing eurobonds would be.’

Some of those who disagree are particularly supportive of the idea of coronabonds. Hélène Rey, for example, says: ‘Coronabonds understood as long-term bonds (30 years plus) jointly issued would be the best response. Otherwise ECB under political pressure.’ Karl Whelan adds: ‘Avoids lots of competing debt issuance. Reduces market concerns about sovereign default on the bonds used to finance the crisis spending.’ And Lubos Pastor at Chicago Booth responds: ‘Coronabonds issued temporarily and eligible for purchase by the ECB would help solve the fiscal challenge in Europe.’

Others who disagree allude to alternative policy measures to coronabonds: Rafael Repullo at CEMFI says: ‘A joint fiscal response would be highly desirable, but it need not be through coronabonds.’ Charles Wyplosz comments: ‘ECB is lender in last resort. Coronabonds or, better, a changed corona-lending by ESM should be first resort.’ And Beatrice Weder di Mauro of the Graduate Institute, Geneva argues that: ‘Europe will need several fiscal instruments to tackle different issues of mitigating this crisis, rebooting and opening borders again.’

Of the experts who say they are uncertain on this statement, Jordi Galí of Universitat Pompeu Fabra says: ‘If the ECB response is sufficient to contain spreads, I agree. But this is uncertain at this point.’ Jan Pieter Krahnen concurs: ‘The ECB can’t do miracles. Rather, we must invent a better instrument than coronabonds – that avoids its traps and convinces its critics.’

Others who say they are uncertain point to the risks. Peter Neary notes that: ‘Coronabonds would only be credible and equitable between countries if issued centrally, and that would require much greater integration.’ And John Vickers at Oxford warns: ‘Need depends on whose perspective you take. Beware political dangers of using this crisis to create eurobonds without federal institutions.’

Finally, of those who agree with the statement, Patrick Honohan says: ‘Not now needed to stabilize national financial markets, but desirable for dealing collectively with what is a common shock.’ Xavier Freixas comments: ‘Coronabonds would allow for irresponsible long government spending, while ECB buying bonds would be a good discipline.’ And Olivier Blanchard concludes: ‘Too strong: can do without bonds but with ECB commitment; more peace of mind with coronabonds.’

All comments made by the experts are in the full survey results.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by iXimus, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Romesh Vaitilingam is a writer and media consultant, and the editor of CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. He is also a member of the editorial board of VoxEu. Romesh is the author of numerous articles and several successful books, including The Financial Times Guide to Using the Financial Pages (FT-Prentice Hall), now in its sixth edition (2011). As a specialist in translating economic and financial concepts into everyday language, Romesh has advised a number of institutions, including the Royal Economic Society, the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE and the Centre for Economic Policy Research. In 2003, he was awarded an MBE for services to economic and social science. He tweets at @econromesh.

Romesh Vaitilingam is a writer and media consultant, and the editor of CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance. He is also a member of the editorial board of VoxEu. Romesh is the author of numerous articles and several successful books, including The Financial Times Guide to Using the Financial Pages (FT-Prentice Hall), now in its sixth edition (2011). As a specialist in translating economic and financial concepts into everyday language, Romesh has advised a number of institutions, including the Royal Economic Society, the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE and the Centre for Economic Policy Research. In 2003, he was awarded an MBE for services to economic and social science. He tweets at @econromesh.