As states across the world increase their interventions in the economy to deal with the fallout from the pandemic, we are likely to see an uptick in state ownership of assets (again). States can use various tools for proactive intervention in economic production and the functioning of markets, in addition to its regulatory and security roles. Mike Wright, Geoffrey Wood, Aldo Musacchio, Ilya Okhmatovskiy, Anna Grosman, and Jonathan Doh undertake an exploratory factor analysis with seven variables that represent various aspects of state intervention in economic activities for 59 countries. They find that not all state interventions should be threatening to business.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made clear the significant variation in how states respond to crises and how those responses are directly linked to the configuration of state apparatus across countries. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments are taking a very active and direct role in their economies, bailing out firms, buying shares in firms, providing loans and developing vaccines themselves. What these various interventions mean is that we are likely to see an uptick in state ownership of assets (again).

Governments are also increasing ownership indirectly through their sovereign wealth funds, increasing their investments in the health, tech, real estate, and travel industries. In Portugal, the government bailed out the flagship carrier TAP Air Portugal, while in Germany the government made a US$9.8 billion capital injection into Lufthansa. Several years ago, the Portuguese government had minority ownership of TAP, but now it owns a 72.5% stake. The airline also received the €1.2bn government loan. In the UK, HM Treasury and the Bank of England provided financial support in the shape of the COVID-19 Corporate Financing Facility for a total of £12 billion to major non-financial non-state-owned European (making a substantial contribution to the UK economy) and UK companies, such as travel companies (British Airways, Ryanair, Wizz Air, Easyjet, RCL Cruises, Stagecoach, Intercontinental Hotels, Airbus), retailers (John Lewis, Westfield and Boots, Burberry), or education and sports (Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, Football Association, Football League, London Business School). The facility was designed to support liquidity among larger firms, helping them to bridge COVID-19-related disruption to their cash flows through the purchase of short-term debt by the UK government.

These observations highlight the importance of understanding the variety of state interventions across countries and how effectively governments address comprehensive and systemic crises. In a recent article on state capitalism and its varieties, we argue that many countries not typically considered as having a big role for the state might become more orientated towards state capitalism. We define state capitalism as an economic system in which the state uses various tools for proactive intervention in economic production and the functioning of markets, in addition to its regulatory and security roles. We identify several key dimensions of direct state involvement in economic activities—as a customer, owner, creditor, etc. To identify dimensions of state capitalism, we rely on an exploratory factor analysis conducted with seven variables that represent various aspects of state intervention in economic activities for 59 countries. Using factor analysis, we end up with three main factors, which we label “non-threatening government”, “state ownership,” and “statism.”

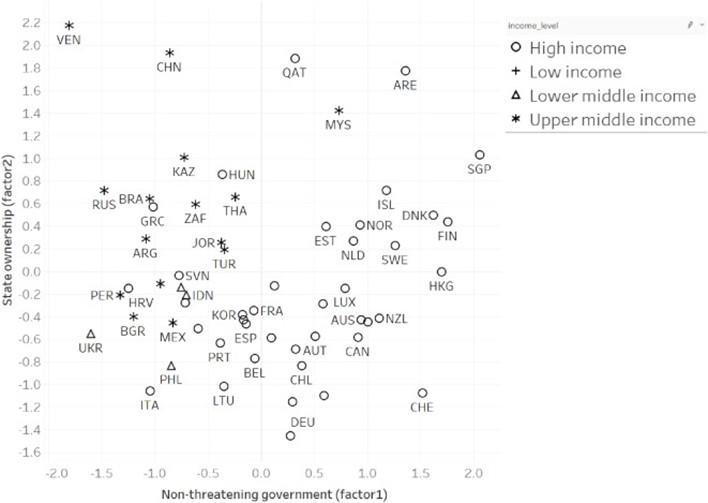

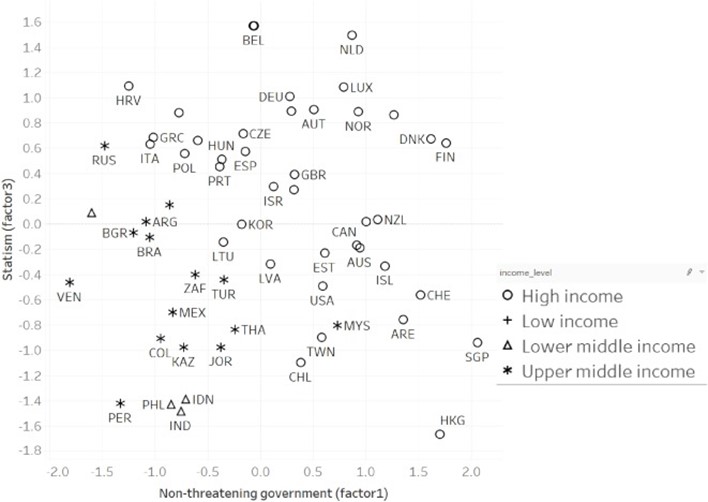

The positioning of countries along the “non-threatening government” and “state ownership” factors is represented in figure 1. The positioning of countries along the “non-threatening government” and “statism” factors is shown in figure 2. Singapore, Malaysia, UAE, Qatar, and Northern European countries, for instance, have relatively large governments that are non-threatening to business, while Venezuela, Russia, Ukraine, Brazil, and Argentina have large state apparatus (both in terms of ownership and statism) with governments more threatening to the private sector.

Figure 1. Scatter plots of factor 1 (non-threatening government) vs. factor 2 (state ownership)

Source: Wright et al., 2021

Figure 2. Scatter plots of factor 1 (non-threatening government) vs. factor 3 (statism)

Source: Wright et al., 2021

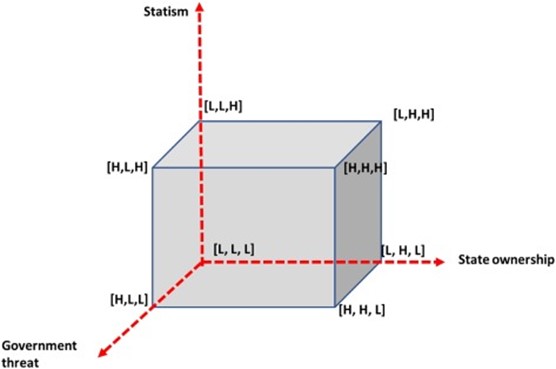

The tools of interventions in the economy favoured by the government might be different across countries. This leads to a categorisation of countries along the spectrum of state capitalism based on the types of tools used for state intervention and the characteristics of state apparatus. Figure 3 is the conceptualisation of varieties of state capitalism along the three dimensions or factors – “government threat”, “state ownership”, and “statism” (L indicates low/medium, while H indicates a high level of a given state capitalism dimension; for example, [L,L,L] at the intersection of the three axes indicates market-oriented states as state capitalism is low on all dimensions). Considering the three dimensions simultaneously is important to correctly characterise the state capitalism profile of a country at a given point in time.

Figure 3. The framework for categorising countries using three dimensions of state capitalism

Source: Wright et al. (2021)

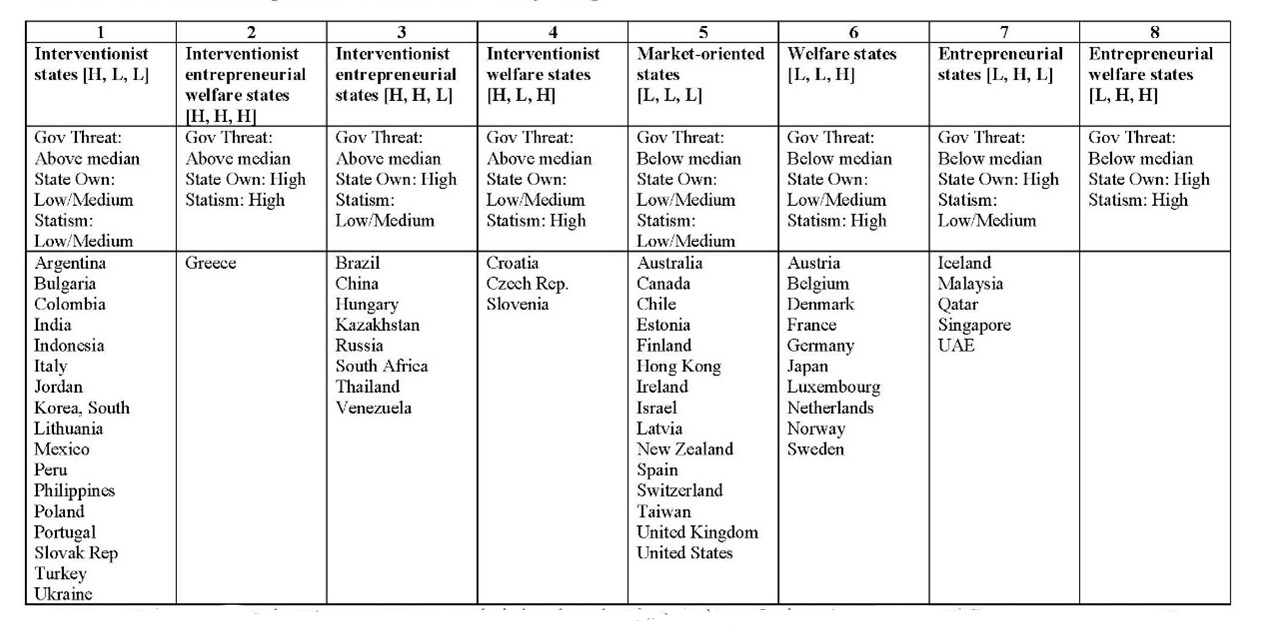

This categorisation of state capitalism is further sectioned into eight categories of countries – from interventionist states to entrepreneurial welfare states, according to how the three dimensions intersect (table 1). This categorisation has an advantage over the existing categorisations of countries in terms of statism or state intervention because it is not dichotomous. That is, we are not trying to code whether a country should be considered state capitalist. On the contrary, we are looking at different shades of state capitalism and coding them into our eight categories with more fluid boundaries, as countries can have combinations of low and high values along each of the three key variables.

There are no countries in the category of “entrepreneurial welfare states,” using the data as of 2014, but that does not mean that with a different period of observation, or different dataset, that category would be empty. As a matter of fact, Qatar may be moving into that category very soon, if it’s not yet there.

This representation should be dynamic – the countries are moving from one category to another over time. For example, with the data taken in 2014, Greece is categorised as an interventionist entrepreneurial welfare state, but Greece could appear in another category if the country data were taken in the years following economic recovery and renewed political stability.

Table 1. Varieties of state capitalism – illustration of country fittings

Source: Wright et al. (2021) Notes: Categories created by the authors using factor analysis based on data from the Fraser Institute, World Bank, and IMD (2014). Each category corresponds to a combination of three factors (factor 1: government threat to business; factor 2: the extent of state ownership; and factor 3: statism). The threshold values are median for factor 1 (= 0.14; with countries where factor 1 < median categorised as non-threatening governments), the third quartile for factor 2 (= 0.5; with countries where factor 2 > the third quartile categorised as high on state ownership), and the third quartile for factor 3 (= 0.66 with countries where factor 3 > the third quartile categorised as high on statism).

This taxonomy of state capitalism we propose can be further extended with more recent data and with data on different countries. In light of recent heterogeneities in government interventions in the economy following the COVID-19 pandemic, a conceptualisation and taxonomy of state capitalist economies could not have been more timely. Also, rather than sounding the alarm about the increase in state intervention, our work highlights that not all state interventions should be threatening to business.

Authors’ Note: This research article is posthumously dedicated to Mike Wright (1952-2019) who was the driving force behind the original ideas.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on State capitalism in international context: Varieties and variations, Journal of World Business.

- expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by paul silvan on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

We’re coming now. See you later!