- China and the EU are expected to make substantial gains from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) due to reductions in transport costs.

- Signing and implementing a deep free trade agreement (FTA) between China and the EU is equivalent to transport cost reductions of 15–20%. The joint policy of the BRI and FTA is super-additive, magnifying the gains from the separate policies.

- Where transport cost reductions are 20% or more, the potential negative effect of the China-US trade war on China is more than compensated for by the BRI initiative.

The Belt and Road Initiative through a trade policy lens

While all Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) trade routes end in Europe, Europeans remain deeply divided on the issue. There is little appetite for turning away investment but there is an identified need for the strategic oversight and planning of inward and outward investment, which underpins market access. The absence of large-scale state ownership across Europe limits the tools available. One approach to tackling this issue is in the form of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), with the potential of a China-EU FTA to follow. Sceptical observers may note that while the EU has been attempting to broker a deal that provides EU companies with the opportunity of more easily making investments in China, substantial Chinese investment has already been taking place in the EU via Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) with individual member states. These largely outdated agreements do not grant the EU equivalent access to the Chinese market. This is part of the motivation for the new investment screening mechanism that came into operation last October and further legislation (currently in draft form) concerning state aid from non-EU countries.

Unlike trade and investment arrangements, the BRI is not underpinned by an agreement outlining detailed rules. There are few empirical economic assessments of the BRI due to the opaqueness of the policy. Our recent research contributes to this small literature by quantifying the trade and welfare impacts of the BRI and benchmarking against other trade policy changes such as the US-China trade war. We also simulate the impact of a China-EU FTA as well as the combined effect of the FTA alongside the BRI. While our main results consider a deep China-EU FTA, for robustness we explore different types of trade agreements. Therefore, the simulations conducted provide an important illustration of the potential trade-offs facing policy makers.

The BRI is centrally, but not exclusively, aimed at lowering transport costs via a plethora of infrastructure projects. The projects are expected to bring down transport costs by improving existing transport routes and opening new ones. Planned improvements include reforms to customs procedures and border management. We may therefore see traders either using the same routes but at a lower cost or switching to lower cost alternatives. Switching would include the possibility of changing the mode of transport, such as moving from sea-routes to rail-routes. In the context of China-EU trade routes, there is a heavy reliance on the Strait of Malacca, which is both a bottleneck and a piracy target. This sea-route is also part of a well-known territorial dispute. The recent blockage of the Suez canal by a single container ship further demonstrated vulnerability and lack of alternative channels for global trade flows. While sea routes are the most cost effective, they have experienced a crisis during the second half of 2020 and, in particular, the first quarter of 2021, when container shipping lines hit capacity limits. So aside from the fact that sea freight is relatively slow, there are additional reasons for Chinese policy makers to develop alternative land routes.

The Belt and Road Initiative and the EU

Our empirical findings, summarised in the bullets at the start of this article, justify China’s massive financial commitment to the initiative, particularly in light of the uncertainty created by the China-US trade war. However, China may face problems regarding asset-quality risks that will further expose Chinese banks. The EU projects are less risky in comparison to the other steps that need to be taken on the BRI road. The EU can therefore capitalise on this opportunity if they can develop stronger strategic oversight of investment flows. However, China must avoid an escalation of the criticisms that have been levelled at their previous investments and must accustom themselves to working to timescales that allow for the appropriate due diligence. There is evidence of steps being taken to address a number of issues; for example, discussions about ‘greening the belt’ are gaining momentum and these may go some way to alleviating concerns that Chinese environmental issues are being offloaded via investments in polluting industries along the belt/road.

Moreover, our results also suggest that the rewards for both China and the EU can be even greater if they are also willing to commit to an FTA, this having been mooted as the potential next step now that the China-EU CAI has been agreed in principle. This gestalt approach requires policymakers to spell out the interconnectedness of the BRI, the China-EU CAI, and FTA initiatives, and this is only likely to happen if China is satisfied that the EU is a strong, stable, and credible partner. Further, China will need to make concessions that are unlikely to be possible in the short-term.

The EU is wary of the balance of gains being weighed in China’s favour; this imbalance is also highlighted in our empirical findings. The BRI countries are already seeking further detail on the initiative. In essence, the project needs to replace its vague slogans with some substance in the form of detail. China also needs to give at least the appearance of engaging with a level of plurilateral/multilateral dialogue. This may support a move from discrete projects to an infrastructure pipeline.

COVID-19 impact

COVID-19 has caused the deepest recession in nearly a century. It also had serious implications for globalisation. The future of the current global division of labour with long global value chains (GVC) is questioned by many observers and policymakers. European Commission President Von der Leyen called for the “shortening” of global supply chains. Similarly, President Macron has called for European “economic sovereignty” by investing at home.

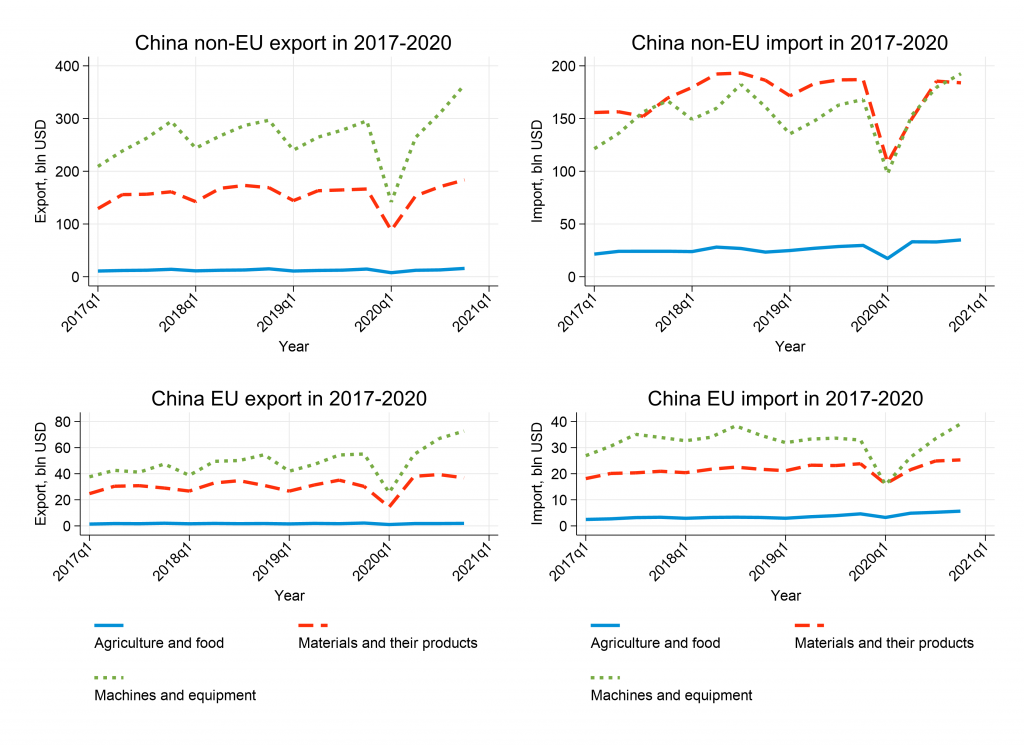

COVID-19 also triggered debates about the future of the BRI. There is evidence of some slowdown in the implementation of the BRI related projects, although the Chinese government remains strongly committed to the initiative. The future of the BRI also looks positive given China’s quick economic recovery. COVID-19 only temporarily halted expansion of Chinese trade in the first quarter of 2020, but it accelerated dramatically in the second half of the year, resulting in Chinese trade in 2020 to exceed pre-pandemic (2019) levels by 18.1% for exports and 6.5% for imports. Analysis by types of products for EU and non-EU countries indicates that exports of machinery and equipment to both EU and non-EU countries, as well as imports of machinery and equipment from EU countries (HS Sections XVI-XXI) have been particularly strong. Other product categories, such as agriculture and food (HS Sections I-IV) and Materials and their products (HS Sections V-XV) have also recovered to their pre-pandemic levels.

Source: General Administration of Customs of People’s Republic of China. Sample covers 43 most important trading partners of China, which covers approximately 80 percent of total trade.

Figure 1 EU and non-EU trade of China in 2017-2020

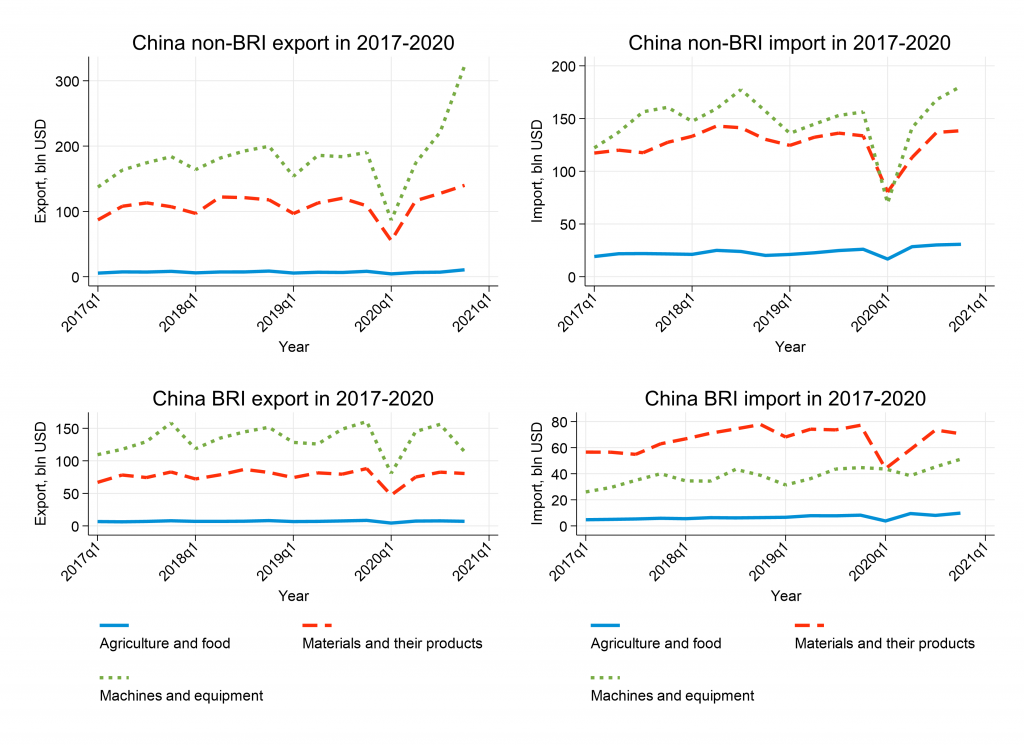

Analysis of the BRI vs non-BRI countries reveal that one of the product/destination categories of Chinese exports that experienced a decline in 2020 was machines and equipment to BRI countries. At the same time, imports of machines and equipment from BRI countries to China has continued to increase.

Source: General Administration of Customs of People’s Republic of China. Sample covers 43 most important trading partners of China, which covers approximately 80 percent of total trade.

Figure 2 BRI and non-BRI trade of China in 2017-2020

What does the future hold?

The impact of COVID-19 on trade was felt through both demand and supply shocks. However, the Chinese economy including trade has rebounded strongly suggesting that the infrastructure projects under the BRI will remain a priority. The BRI can play an important role in reducing, or potentially offsetting, the negative impact of the China-US trade war. At a time when recent elections and referendums have left the trading environment very uncertain, this initiative can offer China a way to counterbalance welfare losses from aggressive trade policy.

For the EU, with the BRI here to stay, policy makers need to work out the best policy tools that may be used to enhance the welfare gains for member states. Additionally, while there has been mention of competing infrastructure development initiatives between the EU and Japan, India and the US that would target investing in low-to-middle income countries, there is currently little substance to these proposals.

For a more detailed discussion of our empirical analysis: Jackson, K. and Shepotylo, O., 2021. Belt and road: The China dream? China Economic Review, 67, p.101604.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

Super