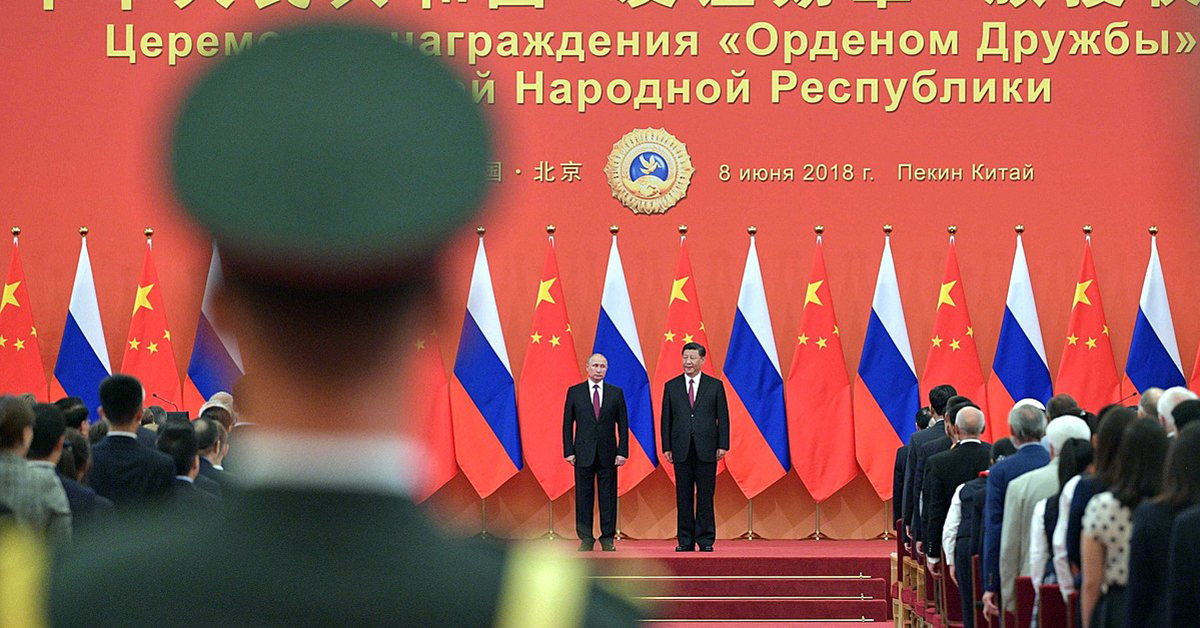

China’s road to peace seems to be a dead end. Immediately after the Munich Security Conference, the Foreign Minister-turned-Director of the Office of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission of the Communist Party of China (中央外事工作委员会办公室主任), Wang Yi 王毅, travelled Eastwards and met his former counterpart Sergei Lavrov, acting Russian Foreign Minister, to later also meet Russian President Vladimir Putin. Just in time for the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China had devised a peace plan meant to be a game-changer. However, the results were rather sobering. What used to be five standpoints became twelve tags, which seemed structured more clearly than Wang Yi’s statement a year earlier. Yet, they still did not reveal a clear path to peace. After the National Party Congress, Xi Jinping himself set off to Moscow. During their meeting, Putin and Xi demonstrated an untainted friendship. Nevertheless, promises were made to the high-ranking European officials in Beijing not to engage any further by supporting Russia with weapons or ammunition. The newly appointed Minister of National Defense Li Shangfu 李尚福 shortly afterwards met with Putin and his Russian vis-à-vis Sergei Shoigu, declaring a partnership of “no limits” and vowed to even deepen military cooperation.

Same-same but different: What’s new about the peace plan?

The 12-point peace plan or “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis” does not mark much of a shift. In terms of scope and direction, the points hardly differ from the five points made in Wang Yi’s earlier statement which had been published just two days after the invasion on February 26, 2022. The big change might be the acknowledgment of a “Ukraine crisis” (乌克兰危机) instead of “Ukraine issue” (乌克兰问题) in previous iterations. However, both statements still fail to mention the fact that Russia invaded a sovereign nation.

Already a year ago, China pointed out that they will stand for “respecting and safeguarding the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries”. Also, the protection of nuclear power plants (point 7) and to restrain from the use of nuclear weapons (8) are quite similar in content. The emphasis of preventing a humanitarian crisis (5), the protection of civilians and the establishment of evacuation channels (6) are now mentioned separately, and in comparison, to a year ago, the guarantee of industrial and supply chains (11) as well as the grain delivery (9) supplemented. China also offered its help for reconstruction (12), but remains vague as to the extent on which areas they want to be involved. The Chinese condemnation of unilateral sanctions (10) is less surprising, but highlighted clearly. This is one of the most central indicators for many observers as to why China positions itself alongside Russia. Yet, in both years China has voiced its support for international institutions and bilateral or trilateral negotiations (4).

After being so prominently heralded at the MSC, the little progress of the peace plan comes as a surprise. Maybe not in the sense of having expected China to be the great mediator between the warring parties, but against the backdrop of expectations created over the past year that Beijing yields actual influence over Putin. Wang Yi who met his former counterpart Sergei Lavrov to reiterate Chinese preparedness to support negotiations probably felt more confident on his most recent trip. All expressions of friendship notwithstanding, there is little reason for hope in China’s plan and the Russian leadership is showing little intention to end the war. Yet, it is a credible assumption that Beijing never wanted that war in the first place nor wants it to escalate nuclear or continue because the growing negative repercussions on China’s interests. Against this backdrop, the disappointing outcome is not necessarily an indicator of lack of interest or indeed effort.

What does it mean for the China-Russia autocratic axis?

Among scholars, it seems common sense that the shared narrative of condemning Western “Cold War mentality” and specifically NATO forges a strong partnership between Moscow and Beijing. Nevertheless, reviewing Beijing’s shillyshallying last year, China clearly wishes to not be associated with Russia’s militarily violent behaviour. Within the unshaken comprehensive friendly partnership with Russia, the emphasis on non-alignment is a constant. Wang Yi habitually stresses China’s “best record as a great power” of never having invaded other countries, engaged in neighborhood wars or participated in the confrontation of military blocs. Although the common interest is to weaken the supremacy of the USA, Beijing cares just as much to ensure Russia’s Ukraine attack does not scare off its target group of supporters in the Global South.

Although there are quite some similarities that feed the autocratic axis, there are also deeply rooted differences, e.g. vis-à-vis economic priorities and outlook. As an autocratic regime reinventing itself in the 21st century, Beijing wants to expand its innovative economy and technological approaches, seeking to build-up global influence associated with this progress. Based on this innovative strength, China seeks to be a comprehensive power that offers a security policy rather than being perceived as a security problem.

Over time, the balance of power between the two has been reversed by China’s rise. The Russian Federation has recently been characterized by observers as a junior partner.[1] Along the border, the partnership is being expanded through a pipeline system separated from the European system, but this also implies looming dependency that China is not prepared to enter into like the EU once was. In addition to raw materials, Russia remains an important actor through military technology. Yet, China’s industry is also catching up in this sector, at sea and in space. Notably, the newly appointed Minister of National Defense in China Li Shangfu, an aerospace engineer, has not only been subject to US sanctions for his Russian weapon deals since 2016, but also experienced in space matters – he was director at the Xichang Satellite Launch center for ten years. During that time, China marched greatly forward in aerospace engineering, which has become part of the comprehensive strategy.

Overall, then, China’s position on the political settlement of the Ukraine Crisis is an expression of the partnership between China and Russia, but rather as an expression of how little the two countries agree on how to proceed. In China, a military attack is seen as a last resort. Russia’s actions disturb the ‘harmonious tranquility’ of working in secret – through economic ties, interests, politics and, of course, through intimidation. This is obvious looking at Taiwan, too: the saber-rattling drowned out by half a century of enduring a paradox. Pragmatic solutions, such as accepting passports without accepting statehood. Looking through all the talk of limitless partnership between both autocratic regimes, the so-called peace plan reveals the limits of Beijing’s influence over Putin to end the unlawful invasion of a sovereign country.

[1] For example by Alexander Lukin in China and Russia: The New Rapprochement. Cambridge, UK : Polity, 2018.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the China Foresight Forum, LSE IDEAS, nor The London School of Economics and Political Science.

“Putin-Xi meeting (2023)” by Presidential Executive Office of Russia is licensed under CC BY 4.0.