Face masks are now compulsory on public transport in the UK, but there are fears that wearing them encourages people to feel invincible and move around more. Maurice Dunaiski (LSE), Roxanne Kovacs (LSHTM) and Janne Tukiainen (University of Turku and VATT Institute for Economic Research) look at the effect of compulsory face mask policies in Germany, and find they decrease mobility in the very short term, with no detectable longer-term effects.

As of 15 June 2020, everyone travelling on public transport in England must wear a face covering or risk a fine of £100. The UK government hopes that this policy will help contain the spread of COVID-19, as it eases lockdown restrictions further. Compulsory face mask policies are now in place in over 50 countries.

Several researchers and policymakers have expressed concerns that compulsory face mask policies could backfire. The concern is that such policies could make the public feel safer, and thereby undermine the most important public health advice to contain COVID-19 – which is to maintain social distancing and reduce mobility. This concern was, for example, expressed by the UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), which highlighted the risk that wearing masks could make people feel invincible and therefore be less likely to adhere to other rules around socialising and staying at home.

Do compulsory face mask policies lead to an increase in community mobility? In a new working paper, we study this question using data from Germany. Germany is an ideal case study because different German states (Bundesländer) implemented compulsory face mask policies at different points in time in late April 2020. To measure community mobility, we use geolocated smartphone data from Google’s Community Mobility Reports, which track the number of visits to public spaces (groceries, pharmacies, workplaces, transit hubs) as well as the number of hours spent at home each day. We find no evidence that the introduction of compulsory face mask policies affected community mobility in public spaces in Germany and can rule out even small increases in community mobility.

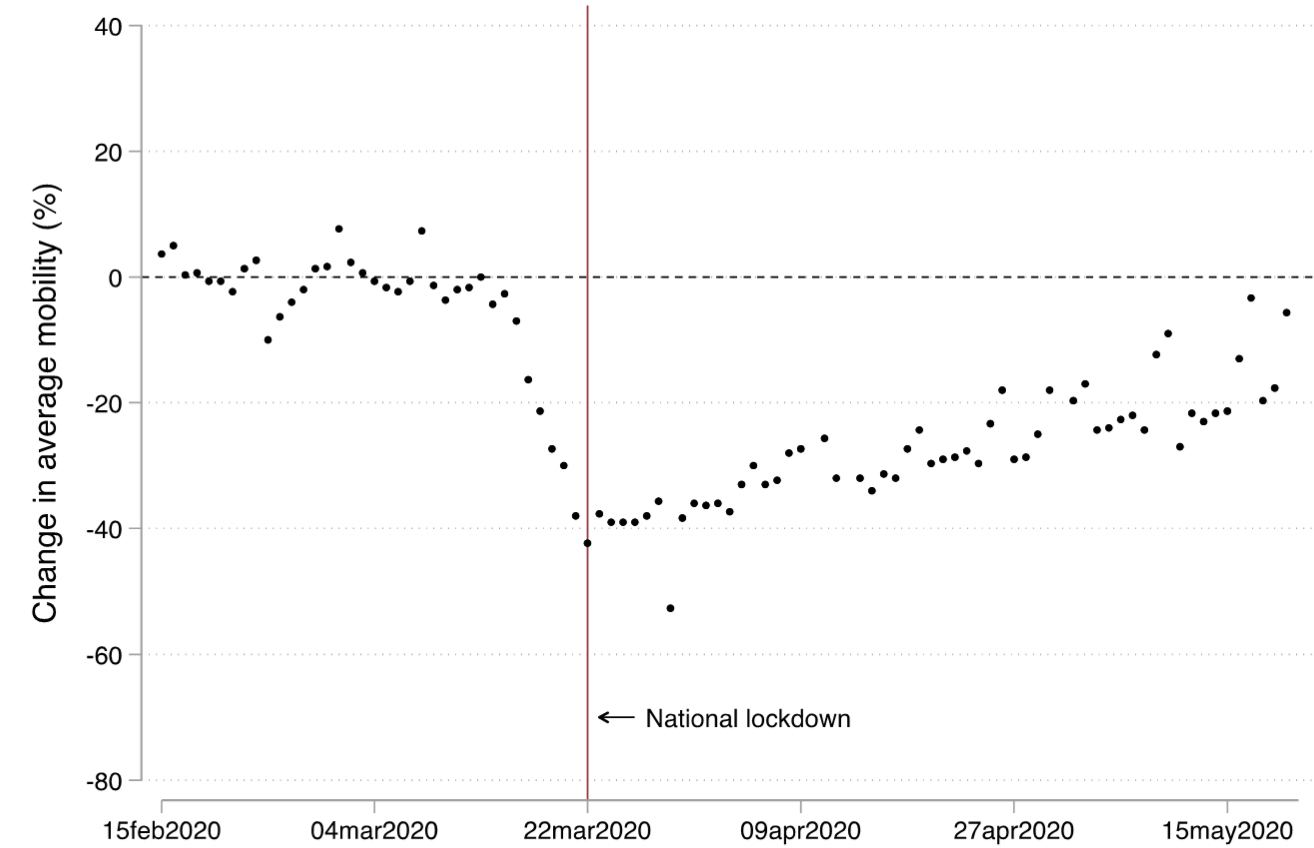

Germany’s lockdown coincided with a drastic reduction in community mobility

Germany implemented a nationwide lockdown on 23 March 2020. As shown in Figure 1, community mobility (how often people visit groceries and pharmacies, workplaces and transit hubs) reduced drastically in the days leading up to the lockdown. In our study, we focus on the period after the lockdown was implemented (23 March to 21 May 2020). Compulsory face mask policies were implemented in late April by all 16 German states – but at different times. The first state was Saxony on 20 April and the last was Schleswig-Holstein on 29 April. The policies make it illegal to not wear face coverings in shops and public transport.

Figure 1: Average mobility in public spaces in Germany (February-May 2020)

Note: This graph shows the percentage change in average mobility in public spaces (groceries and pharmacies, workplaces, and transit stations) for each day between 15 Feb and 21 May 2020 relative to the baseline. The baseline is the median value for the corresponding day of the week in the five-week period between 3 Jan and 6 Feb 2020. Data: Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports.

We find no effect of compulsory face mask policies on community mobility

Because compulsory face mask policies were implemented by different German states at different points in time, we are able to isolate the effect of these policies by comparing mobility patterns before and after the policy change in a treatment group (states with the policy) and a control group (states without the policy). Our research design also allows us to account for other factors that could potentially affect mobility patterns, such as the easing of stay-at-home orders or the reopening of schools.

We do not find evidence to suggest that compulsory face mask policies affect average levels of mobility in public spaces. Our statistical estimates are precise. We can rule out even small increases in mobility that are, on average, larger than 0.03 standard deviations.

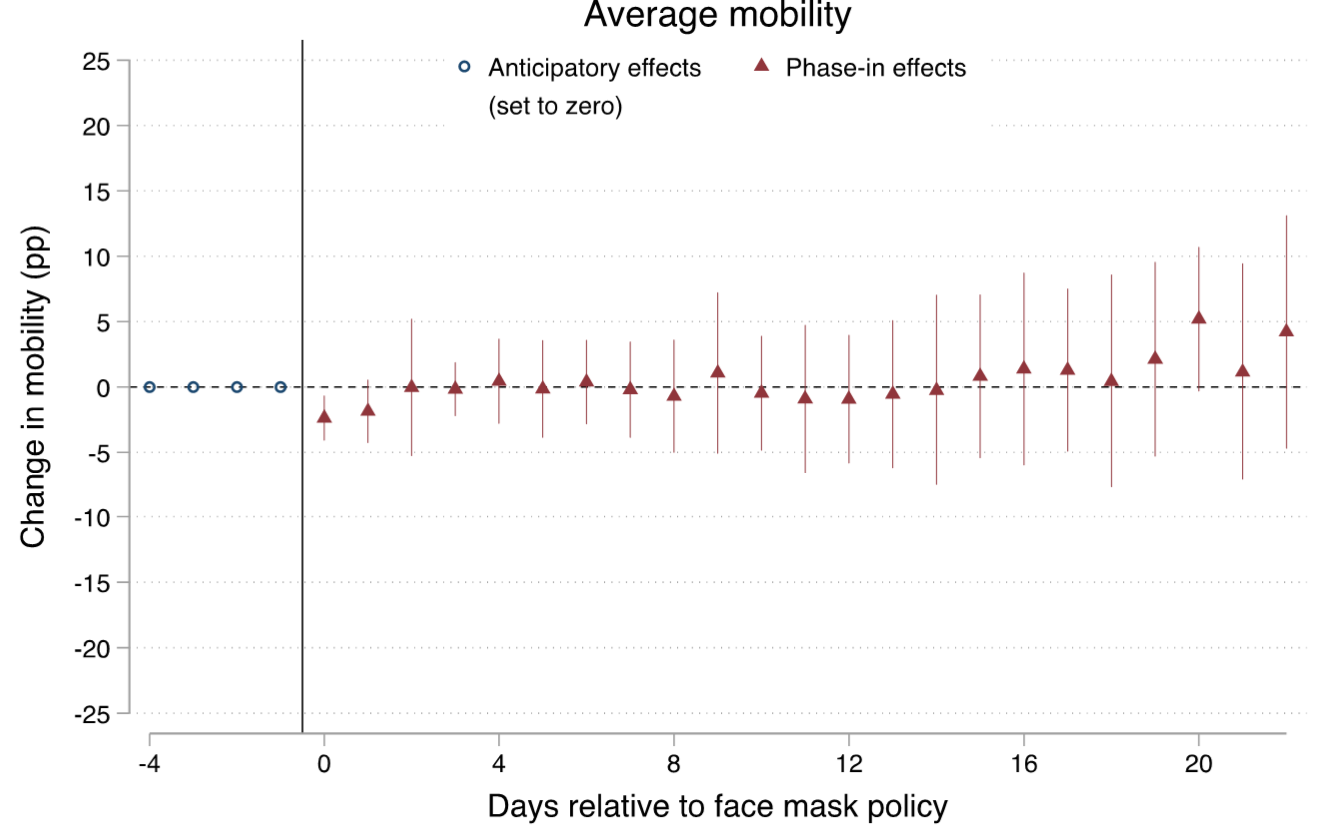

Mobility decreases only in the very short term

Our first result is for the whole implementation period (until 21 May 2020), but we also look at whether the effect of the compulsory face mask policies changes over time. To do so, we use what is called an event study approach – where we estimate effects separately for each day following the policy implementation. Figure 2 below shows the effect of the compulsory face mask policies on community mobility for 22 days after implementation. Whenever the red triangles and corresponding lines touch the horizontal dotted line, the effect is not different from zero (statistically insignificant at the 5% significance level). Compulsory face mask policies only appear to affect community mobility patterns on the first day of the policy change (the left-most red triangle). But the effect is small and amounts to a reduction in mobility of only 2.4 percentage points. We find no significant effects for any of the following days.

We also look at mobility in specific public locations. We find a small reduction in visits to groceries and pharmacies in the first five days following the policy change – with no longer-term effects. We also find that time spent at home increases in the first four days following the policy change – but with no discernible effects thereafter. Finally, we find no significant effects on mobility patterns in workplaces and transit hubs.

Overall, the results therefore suggest that compulsory face mask policies only affect community mobility patterns in the very short term, with no detectable longer-term effects.

Figure 2: Over-time effect of compulsory face mask policies mobility in public spaces in Germany

Note: This graph shows the estimated over-time effect of compulsory face mask policies on average mobility in public spaces (groceries and pharmacies, workplaces, and transit stations) for 22 days after the policy change. Point estimates are obtained from a semi-dynamic event study model, where all treatment leads are set to zero and the panel is trimmed such that it is balanced in time periods (days) relative to the policy change. The model includes controls from our preferred static difference-in-differences model specification: state-specific public holidays, the daily number of new COVID-19 cases in each state (lagged by one day), and dummies for several policy changes that are likely to affect community mobility (lock-down rules being relaxed, secondary schools and retail reopening). Vertical lines represent cluster-robust 95% confidence intervals.

Important evidence for policymakers

Unfortunately, we do not have data to examine whether compulsory face mask policies affect important individual behaviours such as hand-washing and social distancing. However, our results should to some degree alleviate policy makers’ concerns that compulsory face mask policies could backfire by increasing community mobility.

As we do not have data on individual behaviour (only aggregated smartphone data), we cannot be sure why exactly compulsory face mask policies did not affect community mobility patterns in Germany. One potential explanation is that face masks are bothersome to wear or that the face mask requirement serves as a daily reminder to people that the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing and serious – both of which could make some people prefer to stay at home.

Alternatively, it could be that face masks do not actually make people feel any safer and that people therefore simply do not engage in more risky behaviour (and leave the house more often). Further research will be necessary to establish which explanation is more plausible.

Finally, as Germany might be a special case, it is important to also examine the impact of compulsory face mask policies in other countries.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.