China faced a constant shortage of cash in the early twentieth century. Meng Wu and Xin Dong describe how a financial innovation, the indirect issuance of central banknotes by private banks, helped solve this problem during 1915-1945. The banks that became part of the system to supply money also made money. This innovation played an important role in expanding the money supply and enabled different governments to circulate their banknotes swiftly.

Where did cash come from in Republican China? While we often think of central banks monopolising the supply of banknotes, this was not the only way currency can be injected into the economy. Indirect issuance of banknotes was an institutional arrangement among domestic Chinese financial institutions for the. It occurred when an indirect issuer deposits reserves with issuing banks and in return collects the equivalent amount of banknotes from the issuing banks.

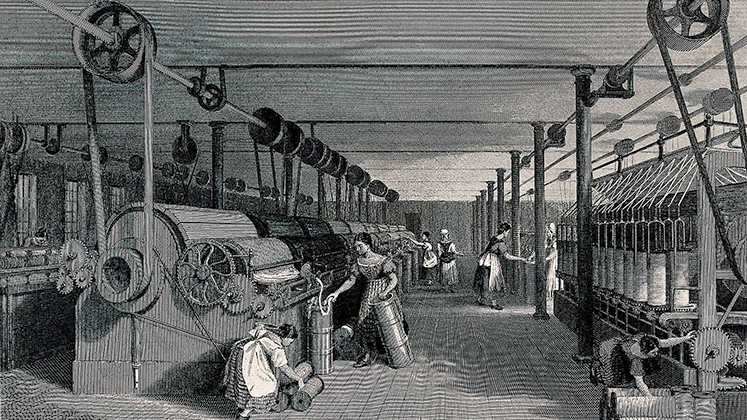

The emergence of indirect issuance can be traced back to 1897, when the first modern Chinese bank, the Imperial Bank of China, was established. To expand its business at the greatest possible speed, the Imperial Bank instructed native banks (qianzhuang) in Shanghai, which had a long-established reputation in financial services and massive business networks, to take its silver-convertible banknotes and issue them on behalf of the bank. In return, native banks were required to deposit silver and short-term promissory notes as reserves, which counted as deposits entitled to interest.

After the republican government was founded in 1912, indirect issuance was standardised to consolidate issuance rights. In 1915, the Bank of China (BoC ) was given a monopoly on issuance and other banks were required to redeem existing banknotes with the BoC banknotes. However, only one year after promulgating the regulation, a moratorium on the BoC banknotes destroyed the credibility of government notes. Following this, issuing rights were once again shared by the government and private banks.

China entered into an era of free banking between the 1910s and 1920s, and indirect issuance became an effective tool in the competition between banks. All domestic financial institutions, including modern Chinese banks, saving societies, trust companies, native banks, and even pawnshops were permitted to participate in indirect issuance. Although all banknotes were claimed to be silver convertible, banks’ reputations and the memory of 1916 moratorium prompted the concentration of the right to issue notes to a few well-established banks.

The free banking period ended in the early 1930s, when the Nationalist army defeated other warlords and reunified China. Facing the consistent loss of silver and aggravated levels of deflation, the Nationalist government decided in 1935 to abandon silver and announced the issuance of fiat paper money, fabi, as the nation’s new and sole legal tender.

To promote the circulation and acceptance of fabi, indirect issuance became an effective tool for the government. As long as the reserve requirements were met, all types of financial institutions, companies, and individuals were allowed to collect fabi and issue it.

As the Second Sino-Japanese War smashed the unification of the currency, the New Nanjing Regime, controlled by the Japanese government, opened the Central Reserve Bank in Nanjing and issued a new type of banknote, the central reserve banknote (CRB hereafter), at par with fabi, and in competition for areas of circulation.

To promote the CRB’s circulation, the regime turned again to indirect issuance. In summer 1941, one quarter of the 260 million Chinese yuan circulating CRB notes was issued indirectly. It surged into over-issuance as the tide of war turned against Japan. When the Japanese government surrendered, the area which it dominated was trapped into hyperinflation. Unlike the Japanese puppet government, the Nationalist government endeavoured to put an end to indirect issuance in order to monopolise the issuance rights.

In 1938, the first batch of indirect issuance contracts between the banks of the nationalist government’s and the indirect issuers was about to mature. However, the disruption of the war and insecurity of the government bonds compelled the indirect issuers to ask the government to extend the contract. Most of the contracts were extended until the war was won.

In the early twentieth century, indirect issuance developed from an informal arrangement into a formal government monetary policy. Our econometric results suggest that a significant positive relationship existed between the indirect issuance business and issuing banks’ income: for every 10,000 yuan these banks issued indirectly, their income increased by 550 yuan.

In a situation beset with great political and economic uncertainty, indirect issuance evolved consistently to adapt to the ever-changing needs of the Chinese financial market.

As a financial innovation, the emergence of indirect issuance fuelled money supply and enabled different governments to circulate their banknotes swiftly. This both contributed to monetary stability and also strengthened the government’s capacity to circulate money.

Our future work will explore the empirical relationship between indirect issuance and banks’ income, and we expect soon to present the study as a working paper.

This blog is based on a presentation to the Conference of Monetary Policy in Historical Perspective (16th-19th Centuries), University of Manchester, 2021.