Recent research has shown that a male labourer who worked 250 days a year could support his wife and three dependent children at a ‘respectable’ standard of living from the time of the Black Death to the industrial revolution. They could afford a varied diet, including some meat, cheese, and beer, as well as pay rent, buy fuel and necessary clothing, and, at times, enjoy a little extra. Indeed, the heady heights of this consumption not only helped propel the economy on a slow but sustained growth path, it also incentivised invention, innovation, and industrialisation. But what of the labourer who could not access so much employment, or the family whose husband was ill, or idle, or lost to his wife and children as a result of death, disease, war, or desertion? What too of the more fortunate, but no less financially crippled couple, whose fecundity left them burdened with many children? How ‘respectable’ were the living standards of these all-too-familiar family types? Even within a life time a standard family would experience periods of plenty counterbalanced by times of belt-tightening. Women and children made significant contributions to household resources throughout England’s history. To what extent did women’s work add to income and offset some of the deficiencies of the man’s earnings to cover his family’s needs? And, if this was still insufficient, were children then drafted into the labour force?

This paper considers the material living standards of a typical albeit fortunate family over the life-cycle, then broadens the experience to cover a range of familiar but less prosperous family types. It takes as its starting point the material welfare afforded by a working couple, a young man and woman each earning an annual income in order to set up their household, through marriage and the arrival of children when the women reduced her paid work commitment to just two days a week at casual rates of pay, through family peak, to old age. We allow consumption smoothing so that money not needed for immediate expenditure could be carried over to the next life-cycle phase. But, where this proved insufficient for family needs, as measured by the cost of the constant-content ‘respectability’ basket in each decade, we compute the number of days work required of the children in the family at the going wage rate to meet these needs.

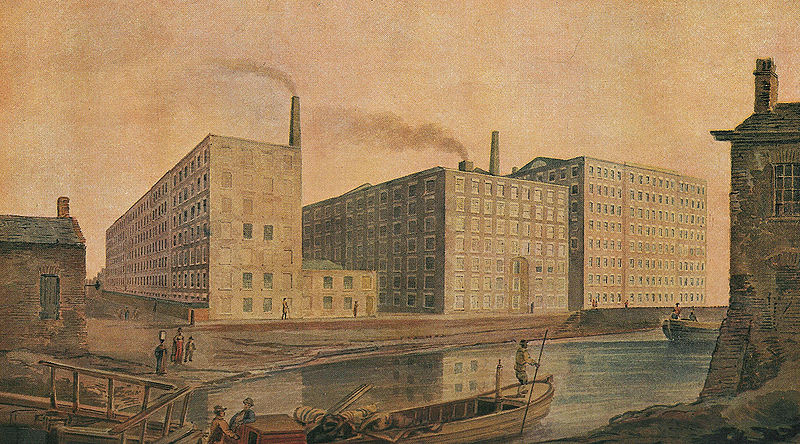

This forms our baseline position. It demonstrates the parlous conditions the family faced at all points in the life cycle prior to the Black Death and the fillip to family welfare caused by the subsequent labour shortage. But some retrenchment occurred in the Tudor era when children’s work was again required. Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to determine whether they actually found this work or instead were forced to resort to charity or the Poor Law. The industrial revolution did not require the fortunate, moderately-sized family to send their children out to labour, provided they were satisfied with the consumption standards set across the previous five centuries. But the possibility of material enhancement and plentiful opportunity to earn may have motivated a move into the workforce, even in these families. Other life cycle stages require some revision of this optimistic scenario. While young people could generally earn enough to carry forward savings to help them survive their early parenting years, older people typically bumped along at levels little above subsistence, although they too shared in the medieval golden age and saw their fortunes rise along with growth brought by a growing and diversifying economy.

These were the fortunate. Both adults in the couple enjoyed persistent good health, survived to a ripe old age, always found employment, and were not overburdened with children. For most, if not all, at some points in their lives, fortune forgot to smile. War was declared or the economy turned down, while individual tragedies, personal failings and sheer bad luck took their toll. The intact family was broken, satisfying even simple consumption needs became an uphill task. We model these scenarios using detailed demographic data to map the range of family size for 1560-1860 and show just how far adrift from the circumstances of our ‘golden’ family so many found themselves.

(a) A ‘large’ family (number of children two standard-deviations greater than the mean) with both the husband and the wife willing and able to work

(b) An ‘average’ family (number of children equal to the mean) with a working wife, but with the husband unwilling or unable to find work

The swelling family sizes of the nineteenth century required many more children to find work to support their siblings. A father’s death or desertion or his ill-health or disability, maybe as a result of hazardous work in one of the burgeoning metal and mining industries, also cast children prematurely into the workplace. These scenarios were not unusual and their increased incidence in early industrialisation can explain much about the persistence even intensification of poverty.

Family size and structure fundamentally altered material well-being. Panning out from a male centre to a more inclusive family frame demonstrates the wide range of experience. It also intimates different routes to economic growth: Tudor reform and expansion co-existed with family deprivation while the early-modern economic-demographic nexus created a plentiful supply of children who were then available as young workers during industrialisation.

This article was originally published on the EHS Long Run blog. The original post can be found here.

This post is based on the authors’ article of the same title published on early view here.

Image source: Wellcome Images, available under licence CC-BY-4.0