Was the Scientific Revolution able to transform learning at the English universities of the seventeenth century? PhD student Julius Koschnick’s research challenges English universities’ reputation as backwaters in the new age of learning. He presents a picture of how students were inducted into science by innovative teachers even though the curriculum remained stagnant.

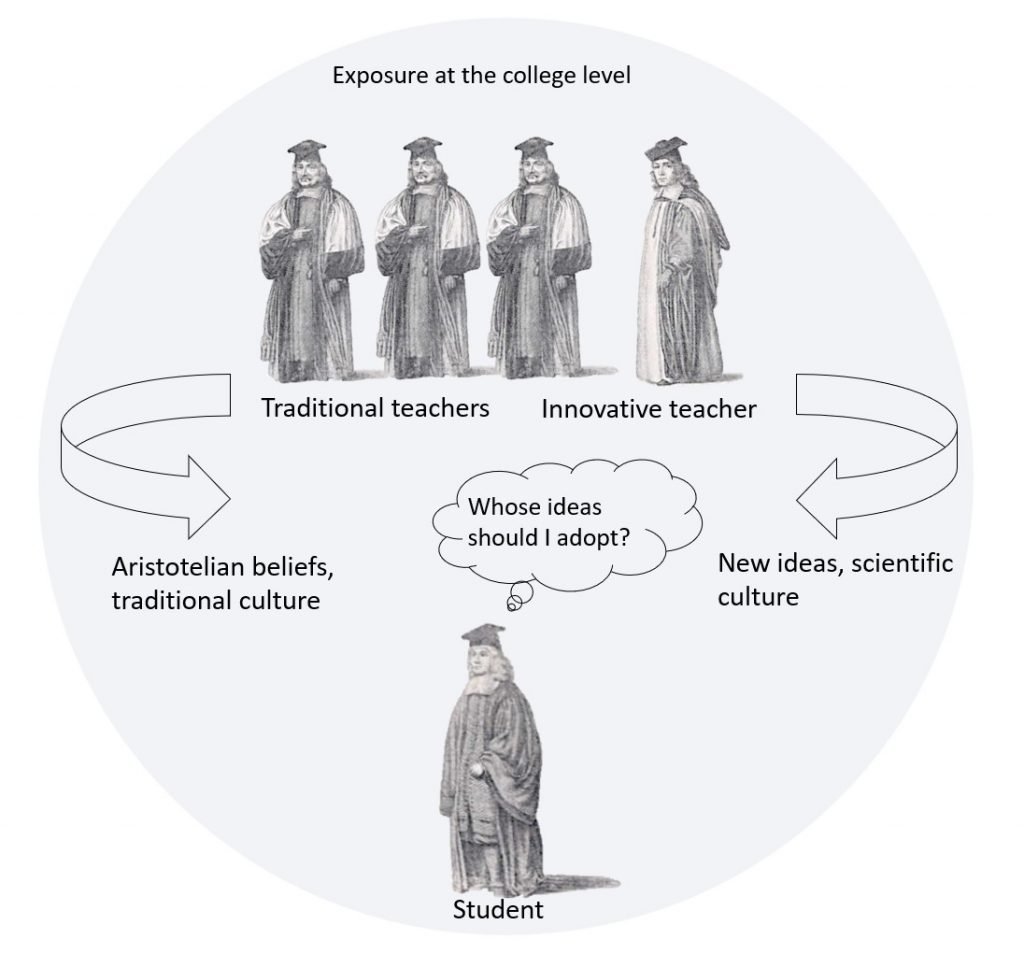

Was the Scientific Revolution able to transform learning at the English universities of the seventeenth century? At that time English universities were bound by formal statutes prescribing the exclusive teaching of a Christianized Aristotelianism of the kind being overturned by new scientific thinkers. Intellectual innovators were few and outnumbered by traditionalists. English universities have often been regarded as backwaters with respect to the ideas of the Scientific Revolution. In The Construction of Modern Science: Mechanisms and Mechanics, Richard Westfall even states that “the scientific revolution was created more despite the universities than because of them” (Richard Westfall 1977, p. 107).

My research has revealed a more positive role for universities in the spread of science during the Scientific Revolution. It examines what factors helped or obstructed the transmission of innovative ideas. Using a new dataset I created of the universe of all 144,748 students at English universities in the seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries, I ask whether teachers passed the ideas of the Scientific Revolution on to their students. To proxy the beliefs of both teachers and students, I matched teachers and students to the titles of their publications. I then use topic modelling and machine learning to identify titles that discussed topics of the Scientific Revolution. I also use membership in the Royal Society as a proxy of revealed interest in the Scientific Revolution.

Innovative teachers did successfully pass their ideas on to the next generation. On average, one innovative teacher influenced about 1 to 2 students. This might not appear like a lot. The dissemination of the ideas of the Scientific Revolution was still significantly slowed down by this majority of traditional teachers. Nonetheless, the intergenerational transmission of ideas played an important part in making academic interest in the Scientific Revolution sustainable in the long run.

The process of transmitting scientific ideas was stronger where diversity of teachers’ ideas in the classroom was higher. Exposure to a greater diversity of innovative ideas reduced the social stigma associated with breaking with tradition. Conversely, if there was a lack of diversity and a strong dominance of traditional teachers, innovative teachers’ effectiveness in to passing their ideas on to the next generation was lower.

These findings help us to understand how tradition suppressed new ideas, but also how the Scientific Revolution was nonetheless able to break with the dominant paradigm of the age. I conclude that often it is not the formal institutional framework that matters for such breaks with tradition or the development of new ideas, but rather the degree of personal freedom, intellectual diversity, and personal interaction within that very institution.

Header image: Merton College, Wellcome M0016060 CC BY 4.0

Julius Koschnick EHS Poster - click to view full size

Julius Koschnick EHS Poster - click to view full size