How does climate change affect the fertility decisions of parents? Using data from 19th century French départements, LSE PhD student Eoin Dignam considers how differences in climate across space and time can affect the incentives of fertility decisions. His work shows that higher summer temperatures are associated with higher fertility, which is caused by adaptations to higher temperatures in the agricultural sector. Eoin presented his findings as a poster at the 2023 Economic History Association conference.

The profound influence of climate on economic incentives, particularly concerning agricultural production, cannot be understated. While existing fertility decision models underscore the intricate interplay of economic and societal dynamics in shaping fertility rates, the synergy between climate variations and economic incentives in the realm of fertility decisions remains a relatively unexplored frontier. My research places climate at the centre of the explanation for why some regions of France experienced the demographic transition at a slower rate than others.

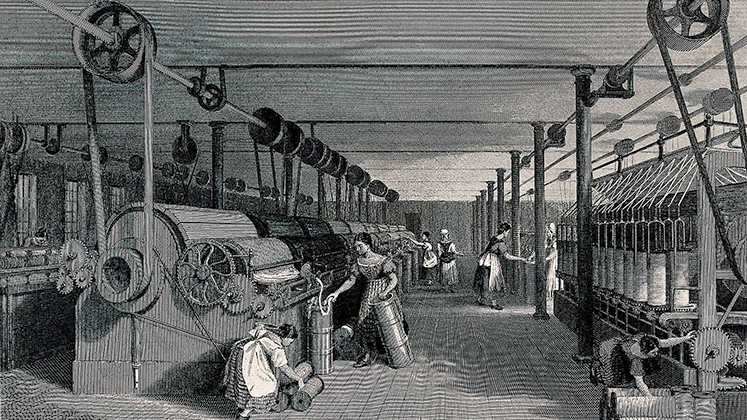

I argue that higher summer temperatures increased fertility by using the quantity-quality fertility model. Rising temperatures prompted a pivotal transformation among agricultural practitioners, shifting their focus from land-intensive pastoralism to labour-intensive tillage. This transition, characterized by a burgeoning demand for agricultural labour, precipitated a decline in industrial employment and, consequently, a reduction in formal education enrolment. This, in turn, augmented in fertility rates by eroding the marginal returns associated with education.

Eoin Digham

Eoin Digham

From Pasture to Tillage

Persistent high temperatures cause significant damage to agricultural production, but the effects vary by the type of farming system. In pastoral agriculture, higher temperatures damage grasslands, reducing the available food stock for animals. Higher temperatures also affect the physiology of pastoral animals, limiting their productive capacity. For example, cows reduce their milk production when experiencing heat stress.

Farms that use tillage, such as cereal farming, experience reduced crop yields at high temperatures. The optimal growing temperature for wheat is between 15°C and 25°C. Temperatures above 25°C cause heat stress, damaging the plant’s development.

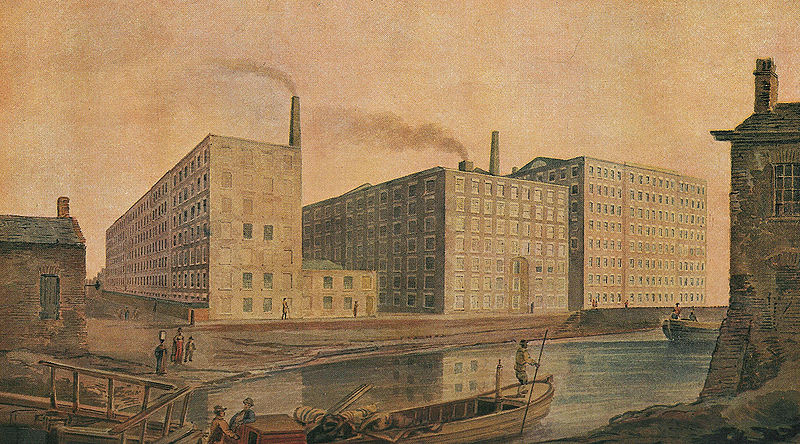

Analysing 19th century agricultural yields, I find that higher temperatures had a relatively larger negative effect on pastoral products, like dairy, than on tillage products like wheat and barley. Climate caused farmers to adapt and switch from land-intensive pasture to labour-intensive tillage. This shift increased agricultural wages, drawing people out of industry and into the agricultural sector.

Why More Tillage Farming Meant Higher Fertility

Under the quantity-quality fertility model, parents have limited resources to spend on child-rearing. Educating your children costs resources (education costs and parents’ time). Children also provide value in the form of care and financial support for families. Parents face a trade-off between child quality (proxied by education) and family size. In crude terms, parents choose between having a small quantity of educated (‘high quality’) children or a high number of low-educated children.

The low human capital levels needed to enter the cereal agriculture workforce meant that there were higher returns from a year of working relative to returns from a year of education. Parents, who switched from land-intensive to labour-intensive sectors, felt a reduction in the costs associated with each individual child.

In accordance with the quantity-quality model, areas of France that experienced higher summer temperatures had higher fertility and diminished educational achievements. For instance, I find that a 1°C increase in summer temperature is associated with a 10 percent rise in the Coale fertility index and a 6-percentage point decrease in the percentage of children enrolled in primary school.

Conclusion

Higher temperatures can change agricultural production, which in turn can alter the incentives of fertility decisions. In the case of 19th century France, elevated summer temperatures impeded the transition from high fertility to low fertility, obstructed the shift from agrarian to industrial sectors, and diminished educational attainments, which together constrained France’s pace of development and growth. This conclusion bears critical significance for contemporary developing nations grappling with the challenges of climate change.

Eoin Dignam

Eoin Dignam