When EU leaders discuss developments in other member states, it often attracts substantial attention in the media. But how do these statements affect the attitudes of citizens toward the EU and issues like austerity? Drawing on a new study, Alessandro Del Ponte illustrates how the rhetoric adopted by EU leaders may inadvertently offend or galvanise the public in neighbouring states.

Citizens often learn through the media what European leaders say about their home country. For example, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has previously exhorted Italians to ‘do their homework’, referring to the need for economic austerity. Meanwhile, the former President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, invited Italians to ‘work more’, ‘be less corrupt’, and more ‘serious’. The Dutch former President of the Eurogroup, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, once even said that southern Europeans ‘spend all the money on drinks and women and then ask for help’. However, leaders also praise other countries for doing things right. For example, Merkel has lauded Italians on several occasions for their ‘impressive’ progress on economic reforms.

This type of rhetoric is becoming more commonplace as a European public sphere emerges, raising the question: How does rhetoric from European elites affect citizens’ emotions and attitudes about economic austerity? In a new study, I have investigated how criticism and praise from European elites affects how citizens think and feel about austerity in their home country.

The study used a survey experiment on two blogs of the Italian newspapers Corriere della Sera and la Repubblica. Blog visitors read a fictional news article in which Angela Merkel addressed Italians. The experiment randomly assigned between participants whether Merkel used words of praise or blame toward Italians and whether the message focused on symbolic aspects (such as values and stereotypes) or on the economy. Messages of praise were designed to convey a sense of commonality among Italians and Europeans whereas messages of blame were designed to communicate a sense of threat to Italian identity. Participants in the control group did not read any article, and both groups answered survey questions about their Italian and European identities, their emotions, and how they felt about austerity.

Social identity theory suggests that people’s reactions to foreign rhetoric will depend on the type of message, but also on how much they feel Italian or European. People for whom being Italian defines who they are will perceive blame on Italy as a personal insult, and any political victory scored by Italy as their own. Alternatively, Italians who feel more attached to Europe will feel less threatened if Italy is criticised, but they will also rejoice if Italy is praised. This happens because Italian and European identity can coexist and mutually reinforce each other.

The results of the study are consistent with the predictions of social identity theory. I found that people who strongly identify as Italians reacted to rhetoric that emphasised economic commonalities between Italy and Europe with enthusiasm and less opposition to austerity. Meanwhile, people with a strong sense of belonging to Europe responded enthusiastically to rhetoric that emphasised symbolic commonalities between Italy and other European countries.

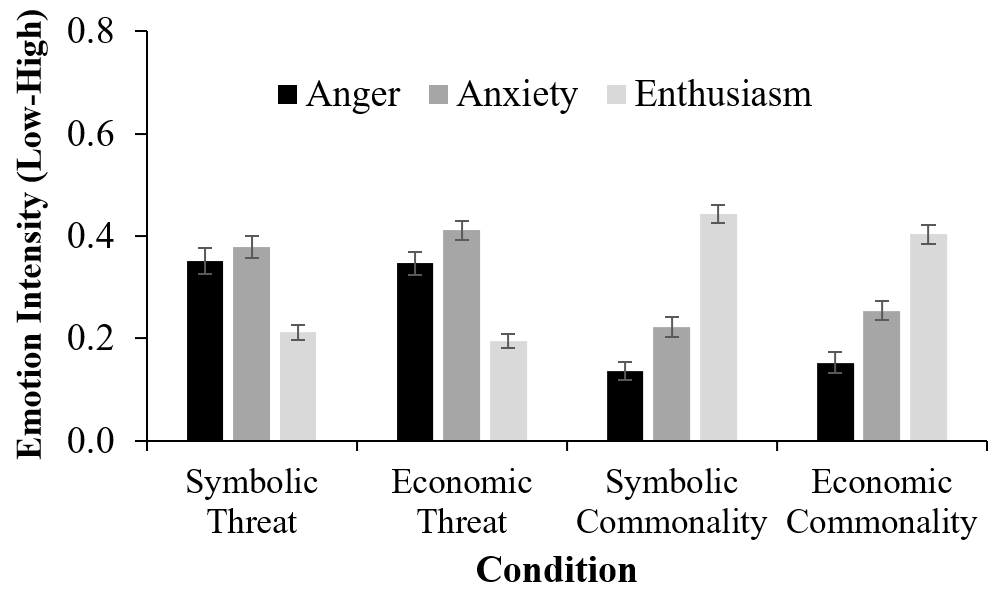

Figure 1: Emotional reactions to blog articles containing different styles of rhetoric

Note: Error bars are standard errors.

To be sure, reading criticism or praise for Italy triggered participants’ emotions regardless of their identification with Italy or Europe (see Figure 1 above). However, participants were much more enthusiastic after reading an article that emphasised how Italy is strengthening the EU if they strongly identified with Italy or the EU.

Figure 2: Economic commonality and Italian identity

Note: Marginal effect of reading the economic commonality article on support for breaching the deficit limit contingent on participants’ Italian identity.

However, changing citizens’ attitudes is not as simple as changing their emotions, especially on a well-known topic like austerity. A search in the online archives of Corriere della Sera and La Repubblica in the year before the experiment revealed that participants had likely read articles about Angela Merkel and been exposed to her rhetoric about austerity. Participants had likely already formed a mental association between Merkel and negativity toward Italy, since the word austerity was often mentioned in the same articles that featured Merkel. Unsurprisingly, most Italians dislike Merkel.

In fact, in the experiment, on average, Merkel’s rhetoric had no effect on participants’ attitudes toward national austerity. However, participants with a strong Italian identity were more accepting of austerity when they read Merkel’s message of praise for Italy’s economic progress (see Figure 2 above) compared to those who did not read any article.

A similar pattern occurred for people who strongly identify as European when they read the article emphasising symbolic commonalities between Italy and the EU. These participants were more willing to give money to the EU in a symbolic tradeoff between prioritising resources for Italy or Europe.

In sum, this research suggests two key points about elites’ rhetoric and national attachments. First, people’s European identity can act as an antidote to the anti-Europe backlash that occurs when leaders make a scathing comment about a member state and it can foster pro-Europe sentiments when leaders use words of unity. Second, people’s national identity can amplify the effects of messages of discord or unity toward the nation.

European leaders should choose their words wisely when they speak about other member states, because their words carry weight. The EU – and especially its policies on fiscal discipline – can be framed as an opportunity to grow stronger together or as a threat to national identities. Vivid rhetoric may inadvertently offend or galvanise the public in neighbouring states depending on whether citizens perceive Europe as hostile toward their nation or on the same side.

As the European media environment becomes increasingly connected, European leaders carry a larger responsibility. Leaders can contribute to fostering European solidarity and bring Europeans closer together by playing up the economic and symbolic commonalities that foster unity rather than the stereotypes and quarrels that fuel division.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in European Union Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council