In March 2020, Jintao Zhu placed as one of two runners up in the annual Posters in Parliament competition which showcases British undergraduate research. Here Jintao shares his research, exploring the symbolic power of animals in representing modern states.

National symbols are an important tool to form national identities. Countries, especially newly formed ones, use national symbols to unify the nationals. The well-known and widely used national symbols include the national flag, national anthem and sometimes the national emblem. However, these are not all- my research takes a particular interest on an unorthodox symbol, the national animal.

My interest on the national animal is not rootless. The practice of using animals to represent humans can be traced all the way back to ancient Totemism. In ancient tribes, people worshipped animals as their ancestors and believed they had the animal’s special power. However, the historical origins are not the only interesting thing. As a symbol, the national animal is arguably a theoretically better national symbol than the flag, anthem or emblem.

Firstly, humans frequently attribute human characteristics to animals (anthropomorphism). This enables the national animal to substantiate the sense of common identity with a concrete one. For example, if the national animal is a tiger, which is popularly perceived as courageous and powerful, then the nationals are inclined to be convinced of their commonality exemplified by this courageous “tiger-spirit”. On the contrary, national flags are formed with simple colour, lines and abstract symbols. While these elements can be linked to the nation’s history or culture, a lot of interpretation is required to draw the link. As most nationals fail to understand the embedded meaning, the national flag serves merely as an assembling signal, without convincing people why they should assemble.

Secondly, humans sometimes treat themselves as animals (positive animalisation). When citizens are convinced of their national animal identities, they unconsciously align their thinking and actions to the national animal. For example, if a citizen believes he is a bald eagle and believes bald eagles always fight for justice, then he is probably inclined to support anti-authoritarian foreign interventions. Abstract symbols like flags have weaker power in achieving the same impact.

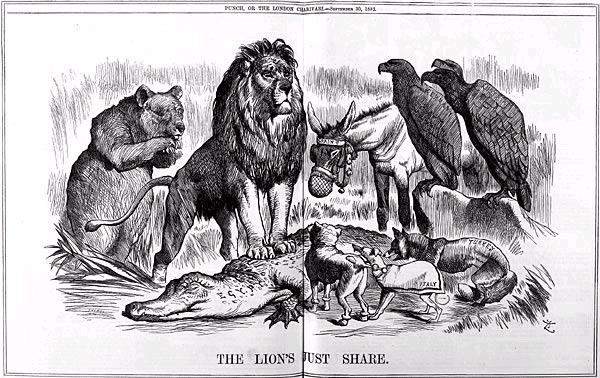

Thirdly, national animals offer a cross-national dimension. Conventional national symbols are inward-looking, without reference to foreign countries. Putting two nations’ flags to each other does not create a meaningful interaction. The national animal has an international realm thanks to the (socially constructed) zoological interaction. The bear-eagle confrontation poster during the Cold War is a good example. The national animal can serve as a metaphorical weapon to boost the morale of the domestic population or justify attitudes or policies towards foreign countries.

However, the national animal is not as commonly used as other national symbols. There are several contributing factors. Firstly, it is hard to establish an effective national animal. In order to achieve the theoretical advantages mentioned above, the nationals must be highly convinced of their national identity. This isn’t easy as human-animal interactions in modern society are diminishing and therefore it is hard for individuals to perceive themselves as animals. Nowadays it is more common to see non-domestic animals in zoos or commercial farms where animals are treated as subjects rather than as an equivalent species.

For many countries, it is hard to pick a suitable species as the national animal due to internal disagreements. As modern countries do not have as highly homogenous populations as the ancient tribes do, different regions or sections of the nation may affiliate themselves with different animals. For example, lions are a prominent feature of the England football badge, whereas Scotland’s fondness for unicorns dates back several centuries. Establishing either one of the two as the national animal could lead to dissatisfaction of the neglected region, causing intensified social division, disunifying the nation.

Besides, even though many countries have official national animals, a good number of them were established for conservation purposes. National animals established with this agenda are likely to be niche species, which do not enjoy a broad domestic popularity. It is therefore hard to convey nationalistic sentiments via these creatures.

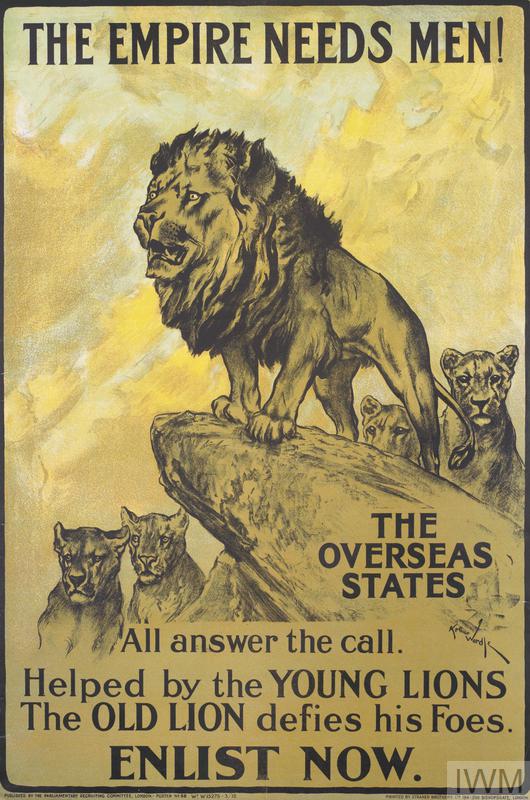

Even if an effective national animal is successfully established, the national animal still requires specific contexts to become salient and have an impact, similar to other national symbols. They require political uncertainties or emergencies such as wars or other crises. During these periods, the masses’ emotional, intuitive impulses are provoked, replacing rational thinking. People are more inclined to embrace their animal spirit rather than logic or sensibility.

Through speeches national leaders have the chance to draw links between an animal’s human attributes and specific action expected from the public, activating national animal identity. Winston Churchill’s wartime speech to the British people described Nazi strikes in the UK as “bombing in the lion’s den.” Churchill’s aim was to urge the British people to fight against fascism by all means as lions are perceived as powerful and uncompromising. More recently, during the Brexit campaign, Boris Johnson exclaimed that it was time to “let the British lion roar,” advocating leaving the EU by comparing the UK to a lion, the independent king of the jungle which is never led by others.

The study of national animals has lots of potential areas to explore further. For example, how does the national animal complement and interact with other national symbols, like the Mexican flag which features an eagle? Or are there distinctive national traits which are derived from animal identities? Does the Russian bear encourage aggression? Does the national animal reflect foreign policies? Does Canada’s intention to replace the beaver with a polar bear show a desire for greater assertion overseas? With such a turbulent global political climate, I am sure national animal identities will be something that we’ll see more of in the future.

The research poster can be viewed here on the LSE Eden Centre Website.

Note: The research paper is still in draft. Any use of the research material should request permission from the author (j.zhu33@lse.ac.uk).

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics.

Main image credit: Richard Lee on Unsplash