The ways in which academics and researchers develop narratives to operationalize key concepts in their field can have significant impacts. Taking the example of economic research, Reda Cherif and Fuad Hasanov explore the formation and diffusion of economic growth narratives and discuss what this reveals about the role of ideas in shaping socio-economic change.

Narratives can be understood as stories that convey complex ideas or theories. They affect our worldview and influence our decisions in ways that challenge the often assumed rationality of homo economicus. Robert Shiller, Nobel laureate in Economics, emphasizes the importance of viral narratives and their impact on economic outcomes, such as the severity of a downturn, the rise and fall of cryptocurrencies, or technological unemployment. More generally, the power of narratives is apparent in politics even when based on falsehoods, monetary policy communication, financial markets’ reaction to uninformative news, and popular understandings of economic policies.

As Keynes observed: “the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else.”

Distilling theories and facts through growth narratives

A central and unresolved question in economics is how to achieve growth. And in practice economists draw from competing theories and empirical evidence to determine the “true” causes of growth and devise growth policies. Such theories might include capital accumulation, human capital, financial development, institutions, innovation, Schumpeterian creative destruction or quality ladders, etc. In the past they would have included, input-output tables, or the role of large firms and industries. Economists confronted with policy choices need to synthesize their ideas, or in other words, come up with a limited set of easily expressed explanations for the key causes of growth. These constitute economic narratives as defined by Shiller, or what we describe here as “growth narratives”.

which growth narratives have been, and are, key ingredients to the recipes for growth that have shaped the global economy?

Taking this as a starting point, one might ask, which growth narratives have been, and are, key ingredients to the recipes for growth that have shaped the global economy? To attempt to address this question, we analysed a novel database of 4620 IMF country reports from 1978-2019. IMF country reports, known as Article IV Staff Reports, cover much of the world (a report is issued every 1-2 years on average for every member country) and report on developments in the economy and economic policy, as well as the views of authorities and IMF staff on macroeconomic policy. They are therefore a good reflection of the economic consensus, or orthodoxy, amongst professional and academic economists and policy circles. Moreover, they feed into a relatively wide audience beyond academia, including policymakers, financial sector analysts, and journalists. As such, they likely represent a significant point in the formation of wider growth narratives.

Narrative elements

Using a vocabulary of 113 distinct terms, we computed relative term frequencies in the reports. We used terms we consider the main growth recipe ingredients: “Infrastructure,” “Governance,” “Education” etc. The list is narrow enough to avoid general terms, for instance “monetary policy”, or those not directly related to growth. We also calculated the total occurrences of each term in three pooled subgroups of reports: Low-Income Countries (LICs), Emerging Markets (EMs), and Advanced Markets (AMs). Finally, we obtained the frequency of each term relative to all the terms in the set, which would inform us on the “amount” of each ingredient in the full recipe.

Interestingly, we found that on average the growth recipe is similar across income groups and that it changes over time (Figure 1). The main ingredients include privatization, governance, transparency, infrastructure, and education. Notably, the frequency of governance and transparency rose sharply in the late 1990s and remained at a high level. In comparison, innovation, technology, industrialization, and export policy have comparatively been ignored. In terms of sectors, services have dominated by a large margin. The frequency of industrialization and industry has been declining since the mid-1980s. Finally, industrial policy, although it appeared at a relatively low frequency, was mostly perceived positively until the late 1980s in the context of AMs. It subsequently faded away until the recent years, when it seems to be making a comeback.

Figure 1. Pooled Growth Recipe Word Cloud (All Economies, 1978-2019 Average Frequencies)

Figure 1. Pooled Growth Recipe Word Cloud (All Economies, 1978-2019 Average Frequencies)

Uncovering dominant growth narratives

Using hierarchical clustering, we identified four key growth narratives making up the prevalent growth recipe. We found a cluster consisting almost exclusively of terms related to industrial sectors, such as services, manufacturing, construction, and agriculture. We interpret it as corresponding to an “Economic Structure” narrative focusing on the study of each industrial sector and their interlinkages. This narrative was the dominant one until the mid-1990s.

Another cluster includes terms broadly related to structural reforms, such as institutions, governance, transparency, and competition. We describe this cluster as the “Structural Reforms” narrative, in which growth is largely explained by the quality of institutions and regulatory frameworks. This narrative was the most influential in the 2000s although continues to be important throughout the 2010s.

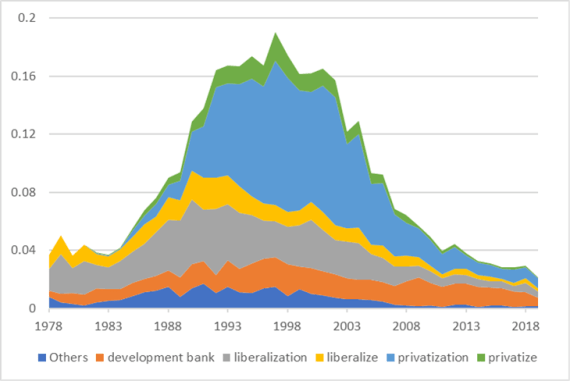

The third cluster is the “Washington Consensus.” It is a cluster mostly consisting in privatization/privatize and liberalization/liberalize (Figure 2). This narrative is based on the principle that privatization and liberalization are beneficial because private industry is managed more efficiently than state enterprise. It was marginal until the mid-1980s, when it subsequently rose, peaked in the 1990s at the time of the transition of many socialist economies, only to become marginal again in the early 2000s.

The final cluster is a collection of many seemingly disparate terms such as productivity, tourism, business environment, doing business, infrastructure, skills, and access to finance, which we call the “Washington Constellation.” As observed by Shiller, the celestial constellations we see have no objective reason to be clustered together, but they form patterns and provide a meaning for the beholder. In this narrative, growth can be affected by many factors. By the late 2010s it has become the most prominent growth narrative.

Figure 1. Pooled Growth Recipe Word Cloud (All Economies, 1978-2019 Average Frequencies)

Figure 1. Pooled Growth Recipe Word Cloud (All Economies, 1978-2019 Average Frequencies)

The rise and fall of growth narratives

Identifying a set of significant turning points in the relative influence of these narratives, we find that they correspond to major political and economic events (Figure 3). The year 1984 marks the beginning of the rise of the “Washington Consensus” and “Structural Reforms” narratives and the decline of the “Economic Structure” confirming the plausible influence of the second Reagan administration in diffusing free market ideas. The year of the Asian crisis, 1997, marks the beginning of the rise of the “Washington Constellation,” followed shortly thereafter by the rapid decline of the “Washington Consensus.”

Figure 3. Total Frequencies of Growth Narratives for All Economies

Figure 3. Total Frequencies of Growth Narratives for All Economies

Changes in the pattern of the relative importance of the clusters may reflect the acceptance or rejection of economic theories, facts or narratives. For instance, the “privatization” frequency started rising rapidly after 1984—amid a push for deregulation and privatization by the second Reagan administration—and peaked in 1997. However, worldwide privatization revenues were relatively stable in the mid-80s to early-90s and only started picking up in the mid-90s. One interpretation is that it may take some time for a change in narratives to translate into widespread policies. This could be the result of inertia in policymaking and the reluctance to experiment until an idea is well established. Moreover, once a new narrative takes hold, it can endure for a long time. It is also likely that certain concepts or policies have simply changed their names such as “Structural Reforms” could have become mostly a rebranding of “Washington Consensus” policies such as privatization. Despite what is seen as fast-paced turnover of ideas in academia, sudden paradigm shifts are relatively rare, indicating further the complex often hidden power of narratives.

“If the world is ruled by little else,” as Keynes talked of ideas, the formation and spread of popular stories or narratives can have large implications on understanding economic phenomena, influencing policymaking, and shaping economists’ own view of how the world works.

This post draws on the authors’ working paper, Crouching Beliefs, Hidden Biases: The Rise and Fall of Growth Narratives.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management, nor the position of the Impact of Social Science blog and the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Rita Morais via Unsplash.