Universities are often invoked as vital drivers of local economic growth, innovative technologies and businesses. However, as James Evans discusses their influence on local innovation may be overestimated in comparison to the role they play in organising and helping these businesses develop.

One argument used against those who say universities are financially unsustainable and too reliant on foreign students is that upending the status quo would hurt innovation and regional economies. This view is widely held; there is longstanding evidence that universities create positive ‘spillovers’ for local economies, and policymakers have sought to exploit this in the hope of boosting growth in lagging regions. Universities are identified as key anchors for clusters in the Investment Zone policy, and last year the government committed to £100m of levelling-up money to university-led accelerators in Glasgow, Manchester, and the West Midlands.

But how good are Britain’s universities at promoting clustering and innovation? One approach to answering this question is to look at where cutting-edge businesses are located and see whether there is clustering near universities. This is something we at the Centre for Cities did in the autumn of last year, using postcode-level data on innovative ‘new economy’ firms to find ‘hotspots’ of innovative activity throughout the country.

But how good are Britain’s universities at promoting clustering and innovation?

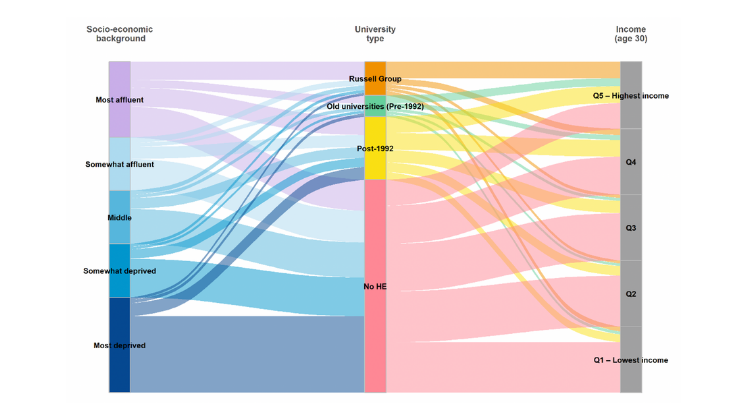

Following research that shows that innovation (and especially valuable ‘unconventional’ innovation) depends on proximity, our research used neighbourhood-sized distance thresholds to define hotspots. Using such tight thresholds not only allowed us to capture the ‘knowledge spillovers’ that drive innovation, they also enabled us to estimate their impact on local economies (Fig.1). We showed that places with hotspots are more productive than those without, and that since the financial crisis they have grown much more quickly than the rest of their regions. In all, we estimate that the businesses within the 344 hotspots we identified employ around 200,000 people and account for 1 per cent of national output.

Fig.1: Location of innovation hotspots throughout the country. Urban and regional economies with relatively more clustered new economy activity are presented in darker hues. Clustering is much more common in the Greater South East than the rest of the country.

Our report also gave insights into the factors that determine where hotspots appear within towns and cities. It turns out that over short distances, innovative firms do not pursue sector specialisation. Instead, hotspots are melting pots of different activities rather than sector-specialised ‘monoclusters’, and they tend to appear where there are many businesses rather than in isolated locations. Skills, transport connectivity, and the presence of large, high-technology employers all appear to matter. Labour market areas with lots of graduates have more clustering per person than those that do not, and neighbourhoods close to anchor employers and well-connected stations are more likely to host hotspots than places further away.

But what of universities? Our research shows that their impact is mixed. A good example of this can be seen in how universities affect the size of their local innovation economies (measured in terms of new economy firms per 10,000 working-age people), which we assessed using a series of regression models. The results paint a seemingly contradictory story. On one hand, we found little evidence that universities increase the amount of innovative activity in their vicinities. On the other hand, universities seem to increase the amount of clustered innovative activity, with research-intensive universities doing so ten times more strongly than other institutions.

universities do not boost the stock of innovative businesses, they do play a role in organising what is there – something that is, if our findings in relation to growth and productivity are to believed, itself is highly beneficial.

Our interpretation of these results is that while universities do not boost the stock of innovative businesses, they do play a role in organising what is there – something that is, if our findings in relation to growth and productivity are to believed, itself is highly beneficial. This speaks to the convening power of higher education, as well as their ability to provide proper facilities for businesses in emerging sectors. Neighbourhoods within 5km of a campus of a research-intensive university are nearly 50 per cent more likely to have a hotspot than those that are further away.

So far so good, but there are two things to keep in mind. First and foremost, our results show that it is only research-intensive universities that have much of an impact on the local innovation ecosystem. This finding, which is in line with research on German universities, suggests that some institutions are stronger anchors than others, and that policymakers ought to be realistic about what different providers can be expected to deliver. Second, while universities positively influence clustering at this level, the size of their impact is much smaller than that of transport connectivity or even large, high-technology employers. They are, therefore, by no means a ‘quick fix’ – the creation of self-sustaining clusters is always going to involve a basket of anchors.

In general, Britain’s universities are better at research than development. When they do generate spin-outs, a combination of bad institutional practices and a lack of nearby infrastructure (especially offices and laboratories), constrains their ability to help them grow.

To a degree our data and methodology provide only a partial picture of how universities shape innovation. After all, all types of higher education institutions play a role in the development of the skills innovative businesses need. Universities could also be having an impact on regional, or even national, scales that we are unable to detect. Yet this doesn’t explain why their local influence is so limited, especially in relation to high-technology employers.

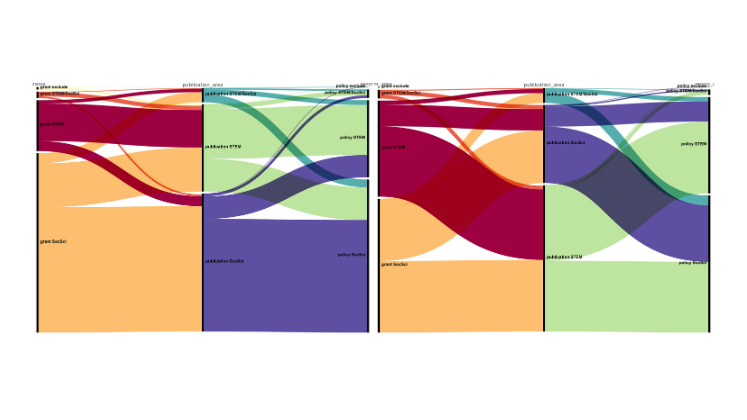

In order to explain universities’ diminished role, it is instead necessary to consider how universities presently interact with innovative businesses at different stages of their life cycles. In general, Britain’s universities are better at research than development. When they do generate spin-outs, a combination of bad institutional practices and a lack of nearby infrastructure (especially offices and laboratories), constrains their ability to help them grow. As the recent review of university spin-outs showed, higher education institutions still take unusually large equity stakes in fledgling firms, and the complexity of spin-out deals wastes time and puts burdens on founders. As a result, many promising businesses simply move away, leaving universities with persistently small pools of businesses rather than self-sustaining innovation ecosystems.

The policy recommendations that flow from this line of argument relate mainly to finance, planning, and how resources should be prioritised. This will mean making tough choices about where new laboratory and office space will be built, as well as which institutions need to be involved. Although it is politically difficult, selecting places with strong research, good infrastructure, and existing high-technology employers will yield greater benefits than spreading investment more widely.

This post draws on the Centre for Cities report, Innovation hotspots Clustering the New Economy.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: HelloRF Zcool on Shutterstock.