Changing the systems and structures that perpetuate inequalities, while difficult, is not impossible. Reflecting on the politics of inequality, Armine Ishkanian notes how scholars, policymakers and social movements around the world have explored numerous ways to reduce inequalities. The path ahead may be difficult, but it’s important to remember that another world is possible.

Politics, as Harold Lasswell famously argued nearly a century ago, is about who gets what, when, and how. While those four questions are important, to understand the politics of inequality, we should also ask why things are the way they are and whether things can be different.

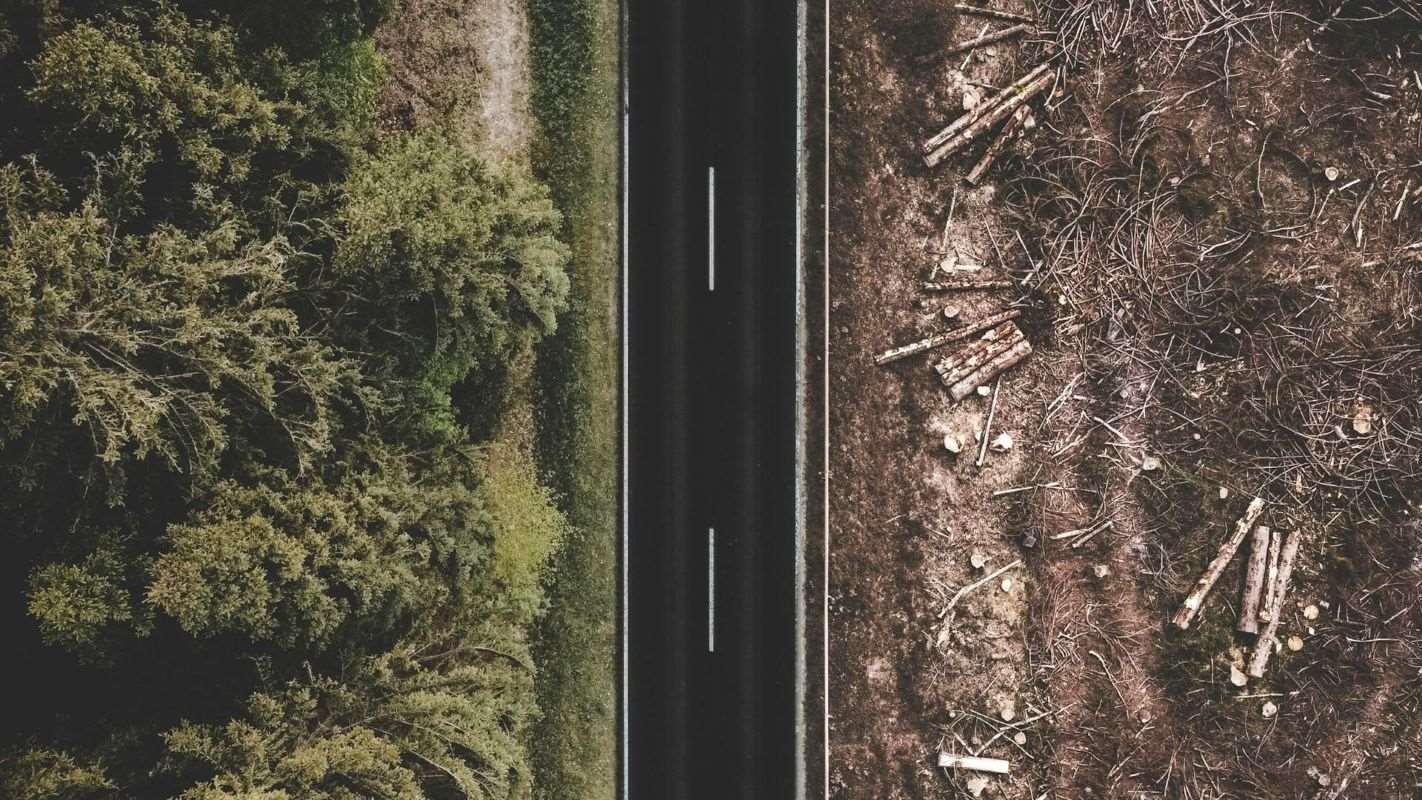

Unlike the laws of gravity, inequality is not inevitable but is rather created and perpetuated by political decisions and social and cultural norms. And, as history demonstrates, changing systems and structures that perpetuate inequalities, while difficult, is not impossible. In Capital and Ideology, Thomas Piketty examines the ways in which ideas have sustained inequality for the past millennium. Inequality, he concludes, “is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political”, with manifestations of it shaped by “each society’s conception of social justice and economic fairness and by the relative political and ideological power of contending groups and discourses”.

Who cares about inequality?

While there is mounting evidence concerning the negative consequences of inequality on the health and wellbeing of both individuals and societies as well as on social cohesion and democratic governance, inequality has not always been on the political or policy agenda. As Francisco H.G. Ferreira argues, inequality, as a policy concern, was identified with the “losing side” in the Cold War. It is only in the past 15 years – and largely following the 2008 global financial crisis – that things started to change. Social movements such as Occupy, the Indignados, and those that fall under the umbrella of the “Arab Spring” propelled inequality into focus and in the case of Occupy, popularised the slogan, “we are the 99%”.

And yet, while global leaders from President Obama to Pope Francis have denounced the dangers of growing income and wealth inequalities, policy responses to redress the balance have been slow to non-existent. As Mike Savage argues, despite the political rhetoric and acknowledgement of the systemic problems generated by wealth inequality, the issue hasn’t been at the centre of political attention – or action. Meanwhile, as Oxfam’s Inequality Inc. report demonstrates, since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, the richest five men in the world have doubled their fortunes at the same time that nearly five billion people globally have grown poorer. Looking ahead, Oxfam predict that the world may have its first trillionaires within a decade.

This raises the question: assuming there is broad consensus that inequality is bad for people, societies, and the planet, why has there been little action to address it?

It isn’t rocket science… it’s politics

Tackling inequality is not rocket science. We’re not seeking to unravel the origins of the universe or to understand the nature of quarks or dark matter. Scholars, policymakers and activists have identified numerous ways in which inequalities can be viably addressed – from advancing tax justice through progressive taxation to putting limits on personal wealth (see the work on limitarianism from Ingrid Robeyns). Indeed, a whole “pluriverse” of transformative initiatives and alternatives (for example around food sovereignty, degrowth and the social solidarity economy) has been put forward as a means to address the multiple, interconnected, systemic crises of the present. In other words, there is no shortage of ideas. What appears to be missing is the political will to adopt and enact the policies that can help reduce inequalities.

According to the hegemonic discourse of neoliberalism, “there is no alternative” (TINA)

The political will is, of course, informed and shaped by powerful interests that will vary across regions and their particular cultures and circumstances. The neoliberal rationality that has dominated governance models globally for the past few decades serves to devalue common ends and public goods, oppose progressive taxation and advocate for a radical reduction in the welfare state – thus scrapping of wealth redistribution as a social and economic policy approach. And crucially, according to that hegemonic discourse, “there is no alternative” (TINA). This phrase was most famously uttered by Margaret Thatcher as a way of saying that there is no alternative to the current economic system and no way for local initiatives to enact such a change.

Another World is Possible

Pushing back against that worldview, the alter-globalization peace and justice movement that emerged from the late 1990s onwards argued that “another world is possible”. Movements that gathered pace from 2010 onwards, such as Occupy and the Indignados, were driven by a desire to create a different world to achieve real democracy and greater equality and dignity for all. The ideas and models discussed by activists, intellectuals and scholars who dare to imagine a world that is different from the status quo may seem quite radical, but in fact there is a long tradition of utopian thinking in social policy dating back to the 19th century which involved imagining and enacting alternative futures.

Today, social movements globally are questioning and resisting the hegemonic forms of neoliberalism and capitalism in order to challenge the “TINA” narrative. Moreover, looking beyond the Global North, movements for equality in the Global South are adopting transformative initiatives and practices of care, for humans as well as non-human species and nature (eg, buen vivir, ubuntu, the social solidarity economy) to embrace more liberatory socio-economic relationships.

Movements in the Global South are adopting transformative initiatives and practices of care – for humans as well as non-human species – to embrace more liberatory socio-economic relationships

For example, in the 2000s, the concept of buen vivir (good living), which is rooted in Andean indigenous traditions, became the basis for the development of social policies in Ecuador and Bolivia following collective mobilisation led by social movements and indigenous communities. The ways in which the ideas encapsulated by buen vivir have been implemented as policies have at times been criticised as being in contradiction with the original concept. Moreover, while there have been some policy wins – such as debt forgiveness for small-scale farmers, fuel price subsidies for the most vulnerable, and an oil moratorium until Indigenous people’s right to free and informed consent is enshrined in law in Ecuador – there is much still to be done to fully realise the alternative approach to development advocated by indigenous movements.

A note of caution is in order, however. While acknowledging how progressive movements have played a key role in putting inequality on the political agenda, it would be a mistake to only focus on such movements. Currently, Gurminder Bhambra and colleagues argue, there has been a resurgence of authoritarian political movements. Some of these movements are opposed to any redistributive policies, whilst others embrace “welfare chauvinism” which, to return to Lasswell’s framework, focus not only on who should receive support but crucially, who should not be helped (eg, migrants, minorities and so on).

The Politics of Inequality: How change happens

There are no grand theories or simple formulas of how systemic change happens because it is context-based and often unpredictable. Understanding how change happens is easier to do when looking to the past where we can identify the factors and dynamics, the roles of various stakeholders, and the events that created windows of opportunity that led to change.

The most progressive changes seem to be happening at the local or municipal levels, rather than nationally or globally, as we see communities creating micro-utopias at a smaller scale. Moreover, achieving systemic change requires connecting what at first appear to be disparate struggles into more comprehensive approaches. This is happening with the emergence of the climate justice movement which not only focuses on addressing environmental issues (eg, melting ice gaps and greenhouse gas emissions) but which also centres equity and human rights – acknowledging the differential impacts of climate change globally and how that is shaped by the past (ie, colonialism). Finally, while it is far more difficult to map how change happens in real time, looking to the past can give us hope that while changing entrenched systems and structures that perpetuate and reproduce inequalities takes time and much effort, transformation is possible. After all, it isn’t rocket science…

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the International Inequalities Institute, the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity programme, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credits: StunningArt via Shutterstock.