Emeritus Professor Margot Light was a research student in the International Relations Department in the 1970s and returned in the late 1980s as a lecturer. She shared her experiences in this talk at the Cumberland Lodge Conference, November 2019.

Being an IR research student in the 1970s

I used to say that the only thing I learnt as a research student was to smoke Benson and Hedges – expensive, normal size cigarettes, rather than small and cheap Players No 6 – and to drink whiskey rather than beer. But of course that’s not really true – I also learnt to try to be witty by saying things like that.

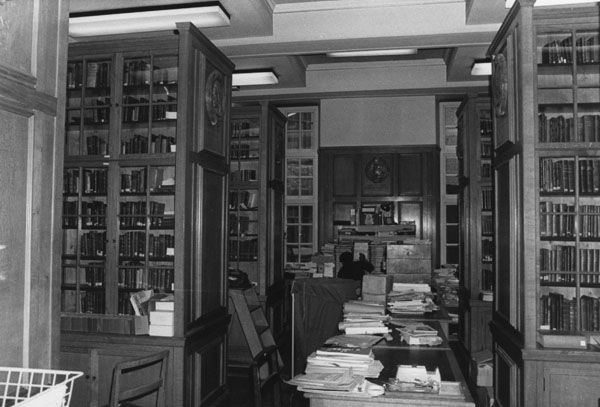

I enrolled as an MPhil student in 1971 and, the LSE being part of the University of London, I hoped in due course to be awarded a University of London PhD. The main offices of the department were in the East Building, but the academic staff had offices all over the School. The Library was still in the Old Building. It was a rabbit warren of a place; as I remember, the IR books were in two small rooms reached by a narrow staircase. There was very little seating space and it was said that if you wanted a seat you needed to be queuing at the door before the library opened in the morning.

When I arrived at the LSE, the Faculty consisted entirely of white British males with the one exception of Coral Bell. And by 1972, there were no exceptions – Coral Bell moved to the University of Sussex, and Susan Strange only joined the department in 1978. The Faculty was predominately young – in fact, since I was a mature student, many of them were not much older than me – and they spent a surprising amount of social time in and around the School.

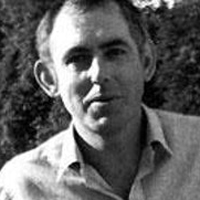

While the Three Tuns, in the basement of St Clements, was popular, the White Horse was more important when I was a student. It was not part of the School, but it was largely frequented by LSE staff and students. This is where Philip Windsor held court – indeed, it was here as much as in the classroom that he influenced a lot of people’s lives, including mine, because it was here that I started joining in discussions about international affairs and other things while drinking whiskey and smoking B&H.

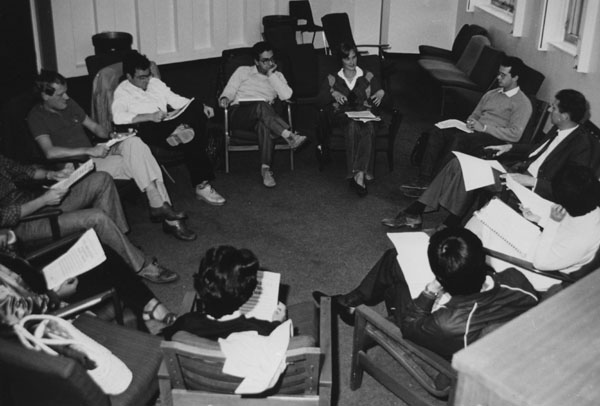

Those, of course, were different times….and not just because smoking was considered smart rather than lethal. There are many other vast differences between then and now. Research students’ lives were incomparably less demanding, but also somehow poorer than now. There was only one seminar for research students and I think it lasted 2 terms.

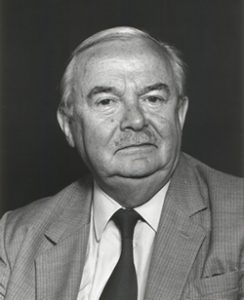

It was conducted by Fred Northedge, who had become a professor and was then Convenor of the Department. It consisted primarily of advice on where to find different types of sources, how to do research, and how to write a thesis. I remember a few pearls of wisdom such as ‘in order to put a book in your bibliography all you need is to have held it in your hands’. There was nothing interactive about the seminar and, as a result, I barely remember any of my fellow graduate students. I don’t think there were any other women, but I may be wrong. The point is that there was no forum where we met regularly, no place where we did our research, whether singly or collectively, no place to bond as a cohort of students.

The one bonding experience I remember from that first year was the Cumberland Lodge conference. Geoffrey Goodwin was director of Cumberland Lodge that year, and he presided over meals. The place was a lot colder and stricter than it is now and much less comfortable. All the accommodation was in the main building and students shared, 3 or 4 to a room. But I remember it as being very exciting, intellectually and socially, and I actually got to know a few people after weeks of feeling very isolated at the LSE.

Northedge’s was the only compulsory seminar especially for research students, but it was not the only seminar we attended. We were advised by our supervisors about other lectures and seminars that might be useful, or conversely, that might harm us. There was a strong ideological divide in the department in those days between Realists and those who favoured Behaviouralism or anything that smacked of American IR – my supervisor, for example, took the view that even though I had already studied some American-type IR theory, attending Michael Banks’ Concepts and Methods course might do me some damage. In fact, not only did I survive the experience – I learnt a lot of IR theory, as well as learning how to structure a lecture. Like many new research students, I attended far too many lectures and seminars, using that year of full time research to fill in on subjects that I hadn’t really studied as an undergraduate.

The other ideological divide in the School was disapproval of anything that might be called Area Studies. Nevertheless, an exception was made for the communist world. When it came to communism, the School hosted Area Studies, even if by other names. For example, Geoffrey Stern taught – amusingly and informatively – a course on International Communism which ranged across communist countries. And in the Government Department there was the Leonard Schapiro Tuesday seminar – one of the last bastions of the Cold War in those détente years — where anybody who aspired to be anything in Communist or Soviet Studies anywhere in the world, strove to speak. It was a seminar open to invited outsiders, regularly attended by people from the FCO and MOD and also by a group of emigres from socialist countries. We used to call them Leonard’s Polish heavies because many of them were Polish, they always arrived a bit late in a group and they clonked their way to the front row where chairs had been left vacant for them. One of them always asked the second question. Leonard, who always appeared to sleep through the seminar, asked the first, devastatingly perspicacious question. The Schapiro seminar was an intimidating event and it took about 11 years of regular attendance before I dared to ask a question.

Perhaps the major difference between expectations of research students then and now is that there was no time pressure or requirement that you would submit your thesis within a particular length of time, or, indeed, at all. My supervisor, Geoffrey Stern, thought that the main purpose of registering for a PhD was to get a teaching job. I saw him regularly and went through paroxysms of anxiety that I had nothing to show him. He was completely relaxed about it, took me to lunch at fancy restaurants like the Gay Hussar and invited me home to meals with his wife and family. He offered me unstinting support even after I left the LSE. He would invite me to give a presentation to his International Communism seminar each year and he would regularly get his producer to summons me to Bush House, where he anchored a weekly Current Affairs programme for the World Service of the BBC, to discuss some item of Soviet news on air.

In those days research students could still get a job if they were ABD — that is, All But Dissertation. Indeed, Geoffrey Stern himself was ABD and so were many of the other faculty members, including Philip Windsor, Michael Banks, James Mayall, Adam Roberts, Michael Donelan, Nicholas Sims, Paul Taylor, Michael Yahuda. And this was not unique to the LSE. It was almost as if it was considered infra dig to actually produce a thesis.

Geoffrey believed that he had been proven right when the University of Surrey offered me a job during my first year. In my second year at the LSE I became a part time student, but I still attended the Schapiro seminar every week and I still regularly frequented the White Horse.

The University of Surrey was very keen to have PhD students so it put pressure on me to transfer my registration. When I wrote to Fred Northedge in 1974 and said I wanted to do this, he seemed very surprised that I was even telling him and not the slightest bit put out. But I still didn’t write my thesis and, snobbishly, for several years I was very sorry that I was NOT writing an LSE thesis, rather than NOT writing a Surrey thesis. However, times changed and it soon became clear that any career progression required a PhD. So eventually I buckled down and wrote it and the rest of my life could begin.

Teaching IR in the late 1980s

Fourteen years after de-registering, I returned to the department to teach, appointed as a lecturer in security studies to assist Philip Windsor. I wasn’t a security studies person but by that time I had become expert in rewriting my CV to match the vacancy advertised. In fact, I first met Mick Cox waiting to be interviewed for a job at Keele University which neither of us got!

By the time I joined the LSE, departments were nested rather than spread around the School, the Library had moved into the Lionel Robbins building (the former headquarters and warehouse of WH Smith) and the IRD occupied the back of the Old Building in part of what had been the Library. That meant that there was still a narrow staircase between the three floors on which we were housed. Few of the ground floor rooms had been real rooms in the Library. My room was a subdivision of a large ground floor reading room, a narrow ship’s galley type room in which if I saw my Masters students together, they had to sit next to one another in a single file while I sat at my desk at the beginning of the file. The IR faculty was no longer entirely British or entirely white and it was no longer predominantly young.

But the gender balance was no better. Susan Strange had just retired so I was the only woman. In fact, I’m tempted to say that I was the first woman because I didn’t know Coral Bell, but I did know Susan Strange and I knew her stellar past, i.e. she had 6 children while being a senior journalist for a major newspaper, moved from there to Chatham House and then to the Montagu Burton chair at the LSE.

She found most men lily-livered and thought feminism was tiresome. In other words, she was SUPERWOMAN and never the woman in the department, in the School, in IR internationally or anywhere. So it was left to lesser women to identify with women students and colleagues, and to represent them in the department and in the School. The main difficulty was persuading the men who predominated in the department and in the School that the playing field wasn’t even and that measures had to be taken to make it more level.

Teaching with Philip Windsor was quite stressful but hugely instructive. It meant auditing his 9 am Strategic Studies lectures – always magnificent — so that I would be able to teach my undergraduate class and co-chair the postgraduate seminar. It also entailed collecting him to ensure that he arrived at the seminar in reasonable time.

The most difficult experience of my academic career arose from Philip falling and breaking his leg at the end of a summer. With two weeks’ notice, I had to give the lectures for the Strategic Studies course. Philip never had a script for a lecture. He simply stood on the podium and spoke for 45 to 50 minutes and then left. No overheads, no blackboard. And even though the course was scheduled to last 15 weeks, sometimes he would finish the lecture in week 13 and announce that he had completed the course. I had recently given up smoking, but within days I was back on the B&H. Fortunately, I was a good note taker — when I read the notes I had taken during his lectures, I discovered that there was a beginning, a middle and an end to each lecture, and an elegant beginning and end to the course as a whole. So I wrote up my notes and gave HIS lectures, even though I didn’t look like him or sound like him and, unlike him, I always had to use notes. I was very glad when he recovered and returned to work. In due course, Chris Coker took Strategic Studies over, and embarked on teaching what I was better equipped to teach, FPA.

Apart from teaching Strategic Studies (the lecture, one undergraduate class and the Masters seminar), like most Faculty members I taught an undergraduate class for the first year IR course which was compulsory for IR students, but also an optional course for other first year students. As I’m sure every Graduate Teaching Assistant knows, teaching this class is quite a challenge. In my second year I also began offering my own Masters course on Soviet Foreign Policy (which soon had to become Soviet and Post-Soviet Foreign Policy). But perhaps the most significant event in IR teaching in those years was Fred Halliday drafting me in to helping develop a new MSc course on Women and International Relations. This was the first IR course in the country to focus on gender. It was a wonderful course to teach and both Fred and I were proud to be part of it.

Teaching LSE students was rewarding but also very exacting. The students were (and, I am sure, still are) amazingly clever, very demanding and always stimulating. The Masters course, in particular, expanded very rapidly and each Faculty member supervised a large number of students.

Working in the department was hugely challenging. Fred Halliday, convenor when I was appointed, invited me to a departmental meeting before I’d actually joined the department. I had previously worked in a highly hierarchical department where you knew your status and acted appropriately. In the IRD, and at the LSE generally at the Academic Board, everyone acted as if they were senior professors, defending their positions robustly against senior and junior colleagues, with no holds barred. The meek, that first meeting persuaded me, would not survive. Forewarned, I rolled my sleeves up before my first departmental meeting in 1988 and kept them rolled up until I retired.

Read about life as an IR undergraduate in the 1960s

Learn more about the foundation and history of the Department of International Relations at LSE