Covid-19 is exposing social inequalities the world over, but homelessness, poverty, and segregation in Brazil’s unequal cities leave large swathes of the country’s population especially vulnerable, writes Matthew Richmond (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

Covid-19 is exposing social inequalities the world over, but homelessness, poverty, and segregation in Brazil’s unequal cities leave large swathes of the country’s population especially vulnerable, writes Matthew Richmond (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

Social distancing measures are exposing social inequalities everywhere that Covid-19 has struck, but this is especially true in the highly unequal societies of Latin America.

In the case of Brazil, 40 per cent of workers operate in the informal sector, meaning they lack labour protections like paid sick leave and redundancy that can cushion the effects of temporary periods without work. While many on low incomes are entitled to welfare programmes, like the famous conditional cash transfer programme Bolsa Família, these are insufficient to keep a family above the poverty line in the absence of other sources of income. Most low-income Brazilians, furthermore, have little or no savings.

Since the pandemic arrived in Brazil, the federal government has shown little inclination to support poor families and informal workers in dealing with its economic effects. Although a 600 real (USD $120) monthly basic income was belatedly introduced, this falls far short of what is needed. It is little more than half of the minimum wage, and far less than what most informal workers would usually be able to earn.

However, to fully grasp the destructive potential of the pandemic in Brazil we must understand how these kinds of socio-economic inequalities articulate with – and are exacerbated by – specifically urban dimensions of inequality. Urban inequalities here refers to the ways in which infrastructure, public services, and economic activities as well as ordinary people, their relationships, and their everyday practices are organised and unevenly distributed across the city.

Brazil is a highly urbanised society, with approximately 85 per cent of the population living in urban areas. Over 16 per cent of the national population lives in the country’s two megacities, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, which have metropolitan populations of 21.6 million and 12.7 million respectively. These are also the centres where coronavirus is currently spreading fastest. Urban inequalities and the politics surrounding them could therefore be crucial in determining how the crisis unfolds.

Covid-19 and Brazil’s homeless populations

One highly visible aspect of urban inequality in Brazil is homelessness, perhaps most notoriously in São Paulo.

With a rise of 9,000 over the last four years alone, there are now estimated to be some 25,000 homeless people in the city, most of whom live in the city centre. Around 33 per cent of this population is drug-dependent. In the neighbourhood of Santa Ifigênia there is a semi-permanent settlement of drug users known as Cracolândia (“Crackland”), where crowds that can be over 1,000-strong often gather to buy and consume crack cocaine.

São Paulo’s large homeless population and its smaller drug-dependent population are hugely vulnerable to Covid-19. Most are unable to wash regularly, let alone comply with stringent official hygiene guidelines. Many have underlying health conditions, such as pulmonary illnesses or immune deficiencies.

Given that many homeless people form groups for mutual aid, protection, and socialising, they also tend to share food and drink, tents and mattresses, and cigarettes or crack pipes, especially in the large agglomeration of Cracolândia. These collaborative practices are fundamental to everyday life and cannot simply be stopped for the purposes of social distancing.

As of 6 April, there have been three confirmed cases of Covid-19 amongst the homeless population (though the true number is expected to be far higher), and none have yet been confirmed in Cracolândia. However, the fear is that if Covid-19 does arrive, it will spread rapidly and with devastating force.

Indeed, even if it has yet to fully arrive, São Paulo’s homeless populations are already feeling its effects. The complex social and economic networks of the city centre, which allow them to survive day-to-day, have been decimated by social distancing. Homeless populations rely on everyday flows of workers, residents, and visitors who provide donations or pay for odd jobs like washing windscreens or supervising parked cars. They also rely on small businesses that may offer them casual employment as cleaners or manual labourers, not to mention the lanchonete diners that provide cheap food and sometimes give out leftovers.

With everyday urban flows grinding to a halt, these populations have become increasingly dependent on the already under-resourced and overcrowded services offered by state agencies, NGOs, and churches. While city governments have begun to explore emergency measures, at best they will only be able to mitigate the effects of Covid-19 on the precarious health and livelihoods of their most marginalised populations.

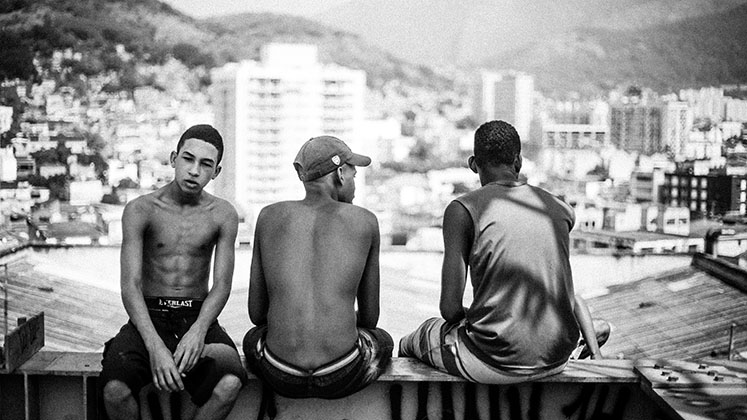

Covid-19 in Brazil’s favelas and peripheries

The simultaneous health and economic impacts of Covid-19 are magnified even further when it comes to the many millions of residents who populate Brazil’s low-income peripheries and favelas.

In part, this is because these areas contain larger numbers of poor residents, who are more likely to be informally employed and to have low levels of savings. A recent study by research institute Data Favela suggested that 72 per cent of Brazil’s 13.6 million favela residents have no savings and so will be unable to survive any sustained period out of work.

These broader social inequalities are also reflected in health inequalities. Favela residents are more likely to suffer from health problems like hypertension or diabetes, and they are less likely to have private health insurance.

However, there are also specifically urban factors at play.

It is common for peripheral and favela homes to be overcrowded, with multiple family members sharing rooms, often across different generations. This makes the effective isolation of the elderly and other at-risk groups almost impossible. Although conditions vary, in more precarious settlements, sanitary infrastructures like running water and sewerage are often inadequate, preventing residents from following official hygiene guidelines. More generally, favelas in particular tend to be densely constructed and populated, with poor ventilation in some areas; together these factors add up to an increased risk that the virus will spread rapidly.

These internal conditions must also be placed in the context of relationships to the wider city. Residents of favelas and peripheries tend to live further away from the essential services that they will need to access during lockdown: this applies to supermarkets, pharmacies, and banks just as it does to health centres or hospitals. Meanwhile, many who must continue to work will have to travel distant areas of the city, in most cases on forms of public transport that will expose them to a higher risk of infection. While there have been relatively few confirmed cases in favelas and peripheries to date, they are likely to spread quickly once they do arrive.

In response to challenges of access, especially in Rio de Janeiro’s steeper hillside favelas, residents have gradually developed complex, collaborative systems that permit mobility and the distribution of essential goods. These typically depend on social proximity, however, and will need to be reconfigured to meet social-distancing requirements. There are promising examples of local groups establishing such arrangements. Meanwhile, broader networks are mobilising to raise money and distribute emergency packages to the poorest families, as well as articulating political demands for more effective responses from the state.

However, the potential of such grassroots initiatives is currently being undermined not only by the structural and long-term institutional exclusion of these populations, but also by the emerging politics of the pandemic in Brazil – and especially the stance taken by the country’s president, Jair Bolsonaro.

Hygienisation and the politics of urban inequality

At present, Brazil’s federal system of government is complicating its response to the pandemic. Social distancing is being imposed by state governors and city mayors, who have limited spending powers. The federal government, meanwhile, has resisted taking the economic measures needed to make the restrictions sustainable.

Instead, Bolsonaro has rhetorically positioned himself against the lockdown, downplaying the threat of the virus and calling for people to return to work. While this may provide some short-term economic relief to those informal workers who follow his advice, it also increases the risk of the virus spreading to the most vulnerable urban populations.

If this does occur, the politics of the pandemic could become intertwined with Brazil’s brutal politics of urban inequality. As Jeff Garmany and I discussed in a recent article, the term “higienização” (hygienisation) is widely used in Brazil to refer to violent state interventions to displace or contain marginalised urban populations, usually for purposes of urban beautification. The term almost certainly comes from “hygienism”, a movement of nineteenth-century European epidemiologists and urban planners that sought to redesign cities according to contemporary theories about the spread of disease.

When it arrived in the postcolonial setting of Brazil, however, hygienisation became the basis for violent interventions against poor, racialised masses, whose presence in the city was seen as a threat to civilisation. While hygienisation today tends to be driven by economic and security factors rather than fear of disease, the Covid-19 pandemic could revive such imaginaries, even linking them to existing dynamics of state violence.

This applies in different ways to different marginalised urban populations. As the streets of central São Paulo have been largely abandoned, homeless and drug-dependent populations have become more visible, generating anxiety and rumours amongst local residents about violent robberies. This has already provoked incidents of vigilante violence. It could easily lead to state violence against a population that politicians and elites have long sought to expel from the city centre, and this at a time when civilian monitoring of police may be compromised.

Favelas and peripheries, meanwhile, are already widely seen as sources of urban violence in Rio and São Paulo, and these perceptions are regularly exploited by politicians through mediatised policing operations and even federal military interventions. If Covid-19 and its economic impacts lead to social unrest in these areas, some will be tempted to exploit the situation in these well-rehearsed ways.

As the crisis deepens, Brazil’s brutal politics of urban inequality could provide opportunities for embattled politicians at different levels of government – not least the President himself – to recover their legitimacy by attacking familiar enemies.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This post draws on the author’s article (with Jeff Garmany) Hygienisation, Gentrification, and Urban Displacement in Brazil (Antipode, 2019)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting