The Pan American Union germinated from the seed of a largely failed and frustrating conference. In doing so, it created a model shared by international organisations today. The contributions of the Global South, including Latin America, to institutions at the heart of today’s world order are often forgotten, Tom Long (University of Warwick) and Carsten-Andreas Schulz (University of Cambridge) suggest.

The handwringing over the state of the “liberal international order” (LIO) has reached Latin America. For the last six years, worries about a crisis in global norms and institutions focused on two perceived threats—the internal erosion caused by populist leaders like Donald Trump and policies like Brexit, and the external threat posed by illiberal powers China and Russia.

Now, it seems that shifts in Latin America will add to the mounting challenges to liberal internationalism and complicate the efforts of US President Joe Biden to restore it. Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro demonstrated stubborn popularity despite worries about his illiberalism, undemocratic behaviour, and defiant anti-globalism. Leaders in Colombia and Mexico, Washington’s closest allies in post-Cold War Latin America, question global institutions, rules, and US leadership in increasingly direct terms.

According to its most prominent proponents, the liberal international order is a broadly inclusive, economically open, and (imperfectly) rules-based way of organizing international politics. Critics contend the LIO was never particularly liberal nor inclusive but rested on the projection of US power.

Latin America has a long, complex relationship with the historical formation of the LIO, as research by a growing group of scholars shows. This engagement has been multifaceted, involving contributions, contestation, and co-constitution of LIO’s norms, practices, and institutions. Going back more than a century, Latin America has grappled with—and at times reshaped—practices of multilateralism and the development of international law that are associated with the LIO.

In a recent article published in International Organization, we show how Latin Americans shaped the formation of the world’s first multipurpose, multilateral organization—a model closely associated with the LIO. Today, the United Nations is the archetype of this model; in the Western Hemisphere, the Organization of American States plays a similar role. These organizations rest on broad membership and decision-making rules that give all members a voice (although not always an equal vote). They advance cooperation initiatives on a range of issues—peace and security, development, climate, humanitarian assistance, and technical cooperation—under a single institutional roof.

Today, we tend to take such international organizations for granted. However, they are only about a century old. The earliest international organizations, then known as public international unions, focused on a single issue and operated under the auspices of one state or patron. This changed with the emergence of the Pan American Union (PAU), which took shape as a result of divergent Latin American preferences and rounds of bargaining with the United States. In doing so, the PAU introduced a new institutional form, thus creating the mould from which the United Nations was later cast.

An organisation diverging from its European counterparts

The Pan American Union germinated from the seed of a largely failed and frustrating conference: the First International Conference of American States, held in 1889-1890 in Washington, DC. One of the few visible results of that conference was the creation of a small office, the Commercial Bureau, to gather and disseminate information on trade and tariffs among the states of the Western Hemisphere.

The proposal for the Bureau emulated a similar union being formed in Brussels at the same moment. However, while the Brussels union—and its European counterparts that addressed issues like telegraphic communication and postal services—soldiered on at its narrow task, the inter-American Commercial Bureau became something quite different.

Soon after the Bureau was founded, Latin American members grew frustrated by US control of the body and by its narrow focus on a US-dominated commercial agenda. Like the public international unions in Europe, the Commercial Bureau sat inside the US State Department, both physically and in terms of organizational control.

Representatives of several larger Latin American states threatened to leave the organization unless it was reformed. In a series of bargains, the United States begrudgingly gave up some control to placate Latin American pressure. The former Commercial Bureau was also granted functions in themes of interest to Latin American states. As the body gained new institutional “layers,” it became a focal point, and something much different than its founders had intended. Indeed, it was the first of its kind.

The Pan American Union was long maligned as a US-controlled talk shop, a criticism also levelled at its direct descendant, the Organization of American States. The institution was formed and consolidated, after all, during the most overtly interventionist period in US-Latin American relations. The idea that the PAU was the “friendly face of US dominance in the hemisphere” has some merit. By some counts, President Woodrow Wilson launched more interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean than any other US president, including initiating a bloody occupation of Haiti and meddling in Mexico’s revolution. But he also oversaw significant consolidation of the PAU and translated Pan-American principles to the world stage.

The United States’ instrumental use of Pan-Americanism is not the whole story. The Commercial Bureau would not have evolved into the multipurpose, multilateral PAU without consistent Latin American demands that regional principles of sovereign equality be better reflected in decision-making rules. Meanwhile, Latin American interests in issues beyond expanding inter-American trade broadened the Pan-American repertoire. Latin American diplomats and professionals engaged avidly with Pan Americanism and the PAU, which coordinated a lively melange of initiatives ranging from architectural associations and scientific conferences to the (still existing) Pan American Institute of Geography and History.

Latin American efforts to reshape these institutions and norms were not always to product of liberal internationalism. Instead, these efforts tracked a Latin American diplomatic tradition that we define as “republican internationalism”. With roots in the nineteenth century, Latin America’s republican internationalism prioritized a vision of a more inclusive international order, focused on sovereign equality and non-intervention, regional solidarity, and international law and arbitration.

These principles remain entrenched in the state-centric operation of the inter-American system. However, the PAU’s shadow extends beyond the Western Hemisphere. Although there is little evidence that the European designers of the League of Nations sought to model the new global body on the PAU, the US representatives in Paris—especially Wilson’s close advisor “Colonel” Edward House—were intimately aware of it and saw Pan American principles as having global relevance. Privately, some Europeans actually discarded the PAU because they saw it as too multilateral; they did not want to grant small states the same voice and influence that Latin Americans had achieved in the PAU.

When Latin Americans looked at the League—and later at the United Nations—they believed there was more than a passing resemblance. The influential Colombian international lawyer Jesús María Yepes wrote of the League: “Nothing similar existed in Europe then. This was, then, a typically American institution, with a physiognomy that belonged to the Western Hemisphere and that, as such, can be considered one of the great contributions of the Americas to the evolution of international politics.”

The contributions of the Global South, including Latin America, to institutions at the heart of today’s world order are often forgotten. Treating such bodies only as the result of great-power bargains distorts our understanding of their history and limits how we see them in the present. Smaller states often view international organizations as friendly environments that offer voice and vote. The case of the first multipurpose, multilateral international organization shows how those spaces emerged from the diplomatic battles of actors from weaker states.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the author rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

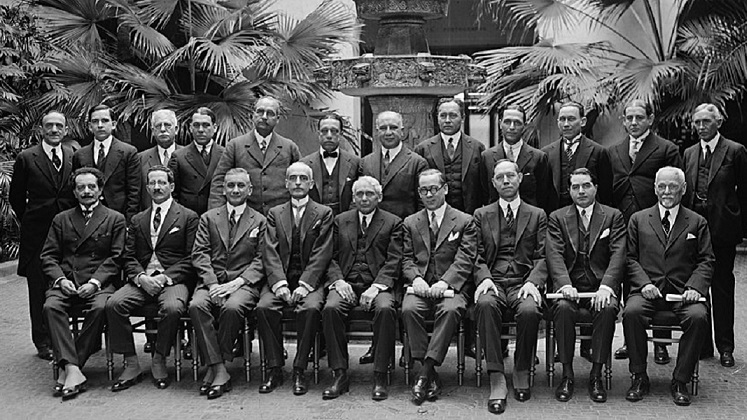

• Banner image: Governing Board of Pan American Union, 1925 / Library of Congress (Public domain)