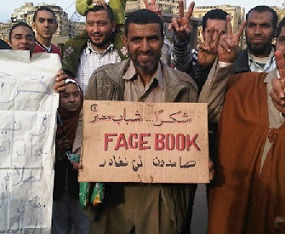

“The revolution was on the street and not online,” Wael Ghonim is keen to assert. On this we all agree. It was not Facebook or Twitter that brought down the regime of Hosny Mubarak. It was the Egyptian people that did that, and it is they who deserve the credit. But there has been considerable debate in policy and academic circles over the role of social media and its impact on the events leading up to the occupation of Tahrir. Unsurprisingly, many important questions remain unanswered, and many facts unknown.

This is why Ghonim’s new memoir, Revolution 2.0, is so valuable. It offers us insight into the world of one of the most prominent online activists in Egypt. Ghonim is the admin of the Kulina Khaled Said (We Are All Khaled Said – WAAKS) Facebook group that was instrumental in getting people into the streets on January 25th 2011. It was WAAKS that set the date of January 25th and it was through WAAKS that over 100,000 people signed up to attend the protests.

Most of us are familiar with the story of Khaled Said, a young middle class guy from Alexandria who was beaten to death by Egyptian police officers in June 2010. Ghonim’s book tells the author’s personal journey after seeing the pictures of Said’s badly beaten corpse, when he decided that something had to be done. He employed his considerable technical and marketing savvy (Ghonim was a senior manager at Google) to launch a campaign against police brutality in Egypt. The rest is history.

Wael kindly agreed to answer a few of my questions after his talk at LSE, organised by the Middle East Centre.

I started off by asking him about the atmosphere in the country in 2010. “Egypt was ready for revolution,” he said. “The people were angry… they were looking for a flagship. It just happened that this was online.” The wall of Ghonim’s WAAKS Facebook page proved a hugely popular place for Egyptians to express their frustrations and served as a crucial venue for the counter narrative that went “against the mainstream propaganda, disseminating the truth about what was happening.”

So why was social media so suited to this task? “The Internet plays a significant role in mobilising people around a cause” he notes.

Through the book, Ghonim illustrates his understanding of his medium – he knew how to communicate with Egyptians online, speaking in a language all could understand rather than solely to the smaller community of committed activists. “People are the ones who mobilise. It’s a tool, there’s no magic in it,” he said. “If you misuse the tool it is not going to work.” This is an important point. Any activist should note that marketing plays no small part in the building of such a movement. “You can’t convince without communication,” he reflects. This is something at which Ghonim has excelled.

Still, some say that there were too few Egyptians online for such a group to really bring about change. But Ghonim is adamant that this was not the case. “There were four million Egyptians on Facebook. That’s a huge number of people and, in the end, it only took 100,000 people to take to the streets to bring down the regime.” What about the charges that the online community in Egypt was too elitist and not really representative enough to spark such events, I asked. How would he respond to that? “It happened” Ghonim retorted. Not a bad comeback.

“The Internet’s biggest achievement was that it helped people collaborate activities and move them from the virtual world to the offline world,” he told me. This is perhaps the key to this topic. For as long as the dissent remained online, the threat appeared to be under control. Revolutions are always won and lost on the streets.

But we should not assume that Ghonim had a master plan to bring about political change. “The movement was very spontaneous and very organic,” he said. “It wasn’t really planned, it was basically reactive.” Indeed, it is clear from the book that he had no idea what would happen 7 months after he started WAAKS.

The fact that Ghonim remained anonymous while running WAAKS was also key to the group’s credibility. He realised that only by remaining anonymous could he avoid the movement from sinking into the same old politicking and power struggles. “It’s much easier to attack a person than an idea” he observed.

WAAKS’ connection with its members was stronger as a result and it allowed people to feel part of the group and, importantly, to contribute their own ideas. Many WAAKS activities were in fact suggested by its members. It was a “leaderless” movement, according to Ghonim.

This flat model of leadership made WAAKS tough for the authorities to stop once boots hit the ground. “It’s organic, there is no structure,” he insisted. Indeed, rather than seeing the group as something that he had created to serve a particular purpose, Ghonim sees it as an inevitable product of the frustrations of Egyptians and the possibilities of online platforms. If he hadn’t done it, perhaps someone else would have.

When asked if such a group could be made again now that the regimes in the region have caught on to the threat, Ghonim thought that this was the wrong question. “Let’s look at this [online activism] as a means rather than a goal,” he said. “If there is a need for it, it will happen.” This may be the view of an optimist, but from the experience of the online mobilisation in Egypt, it is also one with which it is hard to disagree.

Tim Eaton works for BBC Media Action on media development projects in the Middle East. He has recently authored a report ‘Online activism and revolution in Egypt: Lessons from Tahrir’ published by the New Diplomacy Platform.

Revolution 2.0 is out now.