by Daniel W. Round

It is nearly two months since a section of the military tried to overthrow Turkey’s government. The coup attempt has brought about an unprecedented and ongoing restructuring of key state institutions, accompanied by a thorough purge of alleged Gülenists within the state apparatus. Given the circumstances, it is worth taking a look at the state of the main political opposition to the Turkish government as it reasserts and extends its control.

With President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s continuing attempts to centralise and consolidate power in the post-coup era, Turkey’s opposition parties would ideally all have significant roles to play in scrutinising decisions and holding the government to account. The burden is heaviest though on the main opposition, the Republican People’s Party (CHP). Not only is the CHP the second-largest party in the Turkish parliament, it is also the only one in any position to challenge Erdoğan. The hard-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) has more-or-less uncritically signed up to the government’s post-coup plans, while the leftist, pro-minority People’s Democratic Party (HDP) has been effectively frozen out of the political process for months. However, the CHP faces serious strategic problems that have for years hindered its efforts to lead a successful, coherent opposition to the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Over the course of two general elections last year, these strategic issues came sharply into focus. In June’s election the AKP lost 9% of their vote share, a loss that seemed to threaten its single-party rule. However, the CHP was not able to capitalise on the AKP’s decline, with its share of the vote down 1% from the 2011 ballot at 25%. In November’s rerun and after months of instability, many analysts expected the CHP to edge closer to 30%, but the party barely increased its share.

Seemingly unable to move significantly past one-quarter of the vote at general elections, the CHP faces serious challenges from multiple directions. The reasons for the party’s stagnation are basically twofold: (1) an inability to make major inroads with socially conservative AKP voters; and (2) in an increasingly polarised country, challenges from the right and left.

At the same time, there is an increasing gulf between the CHP’s traditional Kemalist-nationalist wing and its social democratic wing. Partly to appease both sides, the tactic of leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu has been to triangulate policy and sentiment. This has been mostly effective at juggling the left and right and securing the CHP’s short-term unity, but ineffective at addressing the party’s long-term strategic challenges and ideological contradictions.

Kılıçdaroğlu is to be credited for moving the CHP away from the worst elements of the rigidity and chauvinism that it was associated with under previous leader Deniz Baykal (1992–2010). His interpretation of laicité, for example, is less restrictive, updated for a country that is now more at ease with its Islamic heritage. However, he has failed to move the party significantly beyond its old, essentialising Kemalist vision of the Turkish state and Turkish identity.

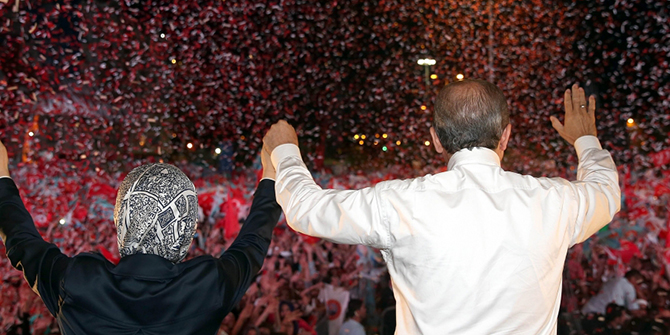

Since the attempted coup, the bases of the AKP and MHP have confidently converged around reactionary ideas and authoritarian policies, such as reinstating the death penalty. Meanwhile, the CHP dithers over its direction. Torn between its history as the party of Atatürk and its recent, partial shift towards European-style social democracy, the CHP continues to struggle to properly define what it stands for and how best to communicate its opposition to the government. While the leadership does not want to allow the AKP and MHP to dominate the unity narrative and so continues to compete with them on nationalist terrain (for instance, at the huge, joint ‘Democracy and Martyrs’ rally’ at Yenikapı in August), those on the centre-left of the party understand that in the long-run, the CHP needs to move further away from its old dogmas in order to appeal to a wider, more diverse cross-section of Turkish society.

At this time of flux, the CHP’s dilemma seems to be whether it continues an uneasy, informal alliance of nationalist unity with the AKP and MHP, or redefines itself as a properly social democratic party that is happier talking to the excluded HDP on the basis of pluralism and human rights. The AKP’s electoral and ideological dominance in Anatolia can only be broken by an alliance between the secular Western coast and the Kurdish south-east – areas that vote CHP and HDP respectively. If the CHP doesn’t become more proactive in building a mass, progressive opposition to the government – reorienting itself towards the trade unions as former leader Bülent Ecevit did in the 1970s, and building bridges with the HDP – stagnation could turn to decline, as has happened with many traditional centre-left parties across Europe in recent years.

It will be difficult for those on the centre-left of the CHP to decisively shift the party and build a progressive alliance to challenge the AKP’s hegemony. The old elite still holds sway, and in the past talk of teaming up with the HDP in the Grand National Assembly has led to significant backlash, with ludicrous accusations of cosying up to the PKK (‘ChPkk’). However, without a show of leadership beyond Kılıçdaroğlu’s triangulation and tactical manoeuvring to try and foster unity, tensions between the two competing CHP visions will continue – as will its hamstrung opposition to an increasingly authoritarian President.

Daniel W. Round is a graduate in American Studies from the Universtiy of Nottingham (2010–14). He has worked and lived in Istanbul (2014–15) and contributes to EA WorldView. Daniel is also a Labour Party activist. He tweets at @Daniel_Round.

Daniel W. Round is a graduate in American Studies from the Universtiy of Nottingham (2010–14). He has worked and lived in Istanbul (2014–15) and contributes to EA WorldView. Daniel is also a Labour Party activist. He tweets at @Daniel_Round.

1 Comments