by Toby Dodge

This article was originally published on Ajil Unbound as part of their symposium on ‘The Many Lives and Legacies of Sykes-Picot‘. The different essays in the symposium attempted to consider both the Treaty’s details and in its wider implications for the Middle East and, more broadly, the study of both international law and international relations.

Introduction

Even before its hundredth year anniversary on 16 May 2016, the Sykes-Picot agreement had become a widely cited historical analogy both in the region itself and in Europe and the United States. In the Middle East, it is frequently deployed as an infamous example of European imperial betrayal and Western attempts more generally to keep the region divided, in conflict, and easy to dominate. In Europe and the United States, however, its role as a historical analogy is more complex—a shorthand for understanding the Middle East as irrevocably divided into mutually hostile sects and clans, destined to be mired in conflict until another external intervention imposes a new, more authentic, set of political units on the region to replace the postcolonial states left in the wake of WWI. What is notable about both these uses of the Sykes-Picot agreement is that they fundamentally misread, and thus overstate, its historical significance. The agreement reached by the British diplomat Mark Sykes and his French counterpart, François Georges-Picot, in May 1916, quickly became irrelevant as the realities on the ground in the Middle East, U.S. intervention into the war, a resurgent Turkey and the comparative weakness of the French and British states transformed international relations at the end of the First World War. Against this historical background, explaining the contemporary power of the narrative surrounding the use of the Sykes-Picot agreement becomes more intellectually interesting than its minor role in the history of European imperial interventions in the Middle East.

The Influence of Sykes-Picot

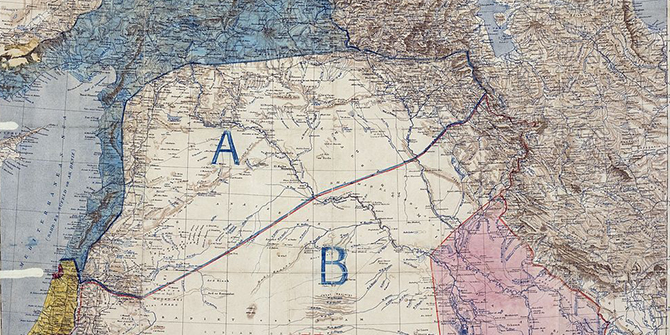

The seizure of Mosul in June 2014 by the rejuvenated forces of the Islamic State (in Arabic ad-Dawlah al-Islāmīyah fīl-ʻIraq wa ash-Shām, or its acronym Daʿesh) came as a shock to the Iraqi government, the United States, and the international community. Later in June, Daesh, with its panache for well-timed publicity, released a video entitled “The End of Sykes-Picot.” A voice-over by a Chechen jihadi explained that Daesh were breaking the colonially imposed borders across the Middle East, whilst video footage showed earthmovers destroying a berm that had previously marked the division between Iraq and Syria.

Within Arab political discourse, “Sykes–Picot” refers to both the colonial conquest of the Middle East by Britain and France during the First World War and covert attempts to retain control over Arab lands in the aftermath of the conflict by dividing the population of the region into separate, weaker states. In the aftermath of the fall of Mosul, Lebanese Druze politician, Walid Jumblatt, very publicly presented his fellow Lebanese politician, Hezbollah’s leader Hasan Nasrallah, with a book explaining the historical genesis of Sykes-Picot whilst he declared its demise.

The fall of Mosul and Daesh’s subsequent activities on the Syrian-Iraqi border also caused an upsurge in media commentary across the United States and Europe. Both academics and senior states people deployed the Sykes-Picot agreement in their attempts to explain the fall of Mosul and the crisis in both Syria and Iraq.

The hundredth anniversary of the agreement, in 2016, brought a fresh wave of media pundits, freshly minted think tank experts, and academics using the agreement to explain Daesh’s continued violence, the on-going horrors of Syria’s civil war, and indeed the whole of the region’s travails in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. This commentary reached its peak in a series of articles written by Robin Wright and an accompanying map. Wright’s sociological and cartographic imagination conjured a stable Middle East delivered through the creation of fourteen new, more religiously and ethnically homogeneous states.

The Sykes-Picot Delusion

A close examination of the history surrounding the European powers’ role in the Middle East during WWI makes the alleged explanatory power of the Sykes-Picot analogy difficult to sustain. As outlined in the book that Walid Jumblatt gave to Hasan Nasrallah, Sir Mark Sykes did indeed reach a secret agreement with François Georges-Picot in May 1916 that allowed for the French and British to divide the Middle East into separate areas of influence in the aftermath f a successful war. This was at the high point of Anglo-French imperial ambition and their optimism about how the war would end. However, even at the time, the confidence underpinning the agreement was questioned, with the head of British military intelligence likening it to two “hunters who divided up the skin of the bear before they had killed it.”

Almost as soon as it was signed, the suppositions underpinning the agreement came under siege and were discarded. The British government made radical policy changes with regards to the Middle East twice in 1917 and again in 1918. The dynamics driving this transformation came first from the U.S. entry into the war, but then from Britain’s own military and political weakness, a military resurgent Turkey, and finally, from the Iraqi population’s rejection of British domination. This meant that the borders of the new states created after the First World War were not the product of a covert Anglo-French conspiracy but were instead shaped by negotiations that reflected British and French imperial weakness, the rise of powerful nationalisms across the region, and a new Turkish state that rejected the imperial division of the old Ottoman Empire.

Instead of deploying the Sykes-Picot analogy and seeking to primordialise Iraq, Syria, and the wider Middle East, it would be more accurate to conceive of Iraq as a dynamic “political field” dominated by a hybrid or polycentric struggle.

This complete transformation of the international system, the Middle East, and Britain’s position in both, led Mark Sykes himself to declare, “imperialism, annexation, military triumph, prestige, White man’s burdens, have been expunged from the popular political vocabulary, consequently Protectorates, spheres of interest or influence, annexations, bases etc., have to be consigned to the Diplomatic lumber-room.” …continue reading

Toby Dodge is Director of the LSE Middle East Centre and Kuwait Professor in the LSE International Relations Department. He tweets at @ProfTobyDodge.

Other essays in the Symposium

- Introduction to Symposium on the Many Lives and Legacies of Sykes-Picot

by Antony T. Anghie

-

Palestine and the Secret Treaties

by Victor Kattan

-

Textual Settlements: The Sykes–Picot Agreement and Secret Treaty-Making

by Megan Donaldson

-

Sykes-Picot and “Artificial” States

by Aslı Bâli