by Benedict Robin-D’Cruz

Chaos across the south

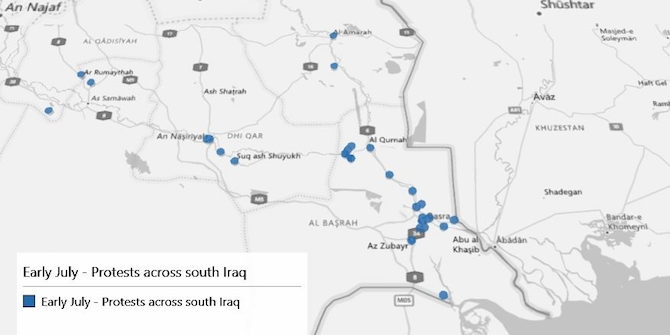

Over the weekend, as protests and violence proliferated across Iraq’s southern provinces, the country’s internet and phone lines went down. The government implausibly claimed there were technical issues with the fibre optic network. In reality, this was a desperate measure taken by an alarmed political elite as provincial governorate buildings were stormed, and the offices of political parties and militias were attacked and burnt.

This turn of events was especially disconcerting for the political elites who had sought to legitimise their dominance of the post-2003 Iraqi state via a claim to represent, and advance the interests of, the previously marginalised Shi’i south, the same constituency who were now burning down their offices.

Reports filtered in of hundreds of casualties and numerous fatalities amongst protesters and security forces. Meanwhile, as lines of communication were cut, the information flowing from the south to the rest of Iraq, and the rest of the world, slowed to a trickle. Worried relatives and friends outside the country struggled to get through to their loved ones.

Videos purporting to show the Iranian-aligned militia, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, opening fire on protesters in Najaf were shared online, and there were reports of similar incidents involving the militia in Baghdad and Samawah.

Protesters in Basra, Iraq’s oil capital whose production accounts for more than 90 percent of Iraq’s total output, targeted operations at key energy sector facilities. It was following the killing of a protester and the injuring of three others near Bahla in northern Basra province that the rates and intensity of protests in the south exploded. The Bahla incident, on 8 July, had involved a reported 500–800 demonstrators from the small town attempting to block off the road to West Qurna 1 and Rumeila oil fields to the south.

In a sign of just how serious the federal government was taking the unrest, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi mobilised 6 Emergency Response Division and 3 Counter-Terrorism battalions from Baghdad to the south. The spectre of a violent conflagration involving a three-way confrontation between protesters, heavily armed militias and security forces loomed large.

What are the grievances fuelling the protests?

This explosion of protest in the south should not come as a surprise. I’ve monitored protest activity in the area over the past year, and in that period there have been over 260 separate protest events.

These have taken various forms. There are frequent, highly localised and small-scale demonstrations with limited and often sector-specific demands (e.g. wage increases, more stable employment contracts, or pleas for infrastructure projects such as roads or sewage systems to be completed).

There have also been large-scale demonstrations, sometimes involving thousands of protesters descending on provincial capital buildings. From November 2017 through April 2018, for example, there were angry, mass demonstrations in Nasiriyah, Basra, Samawah and Rumaitha, amongst other places, opposing Abadi’s reforms of the electricity sector, which were regarded as a privatisation scheme that would drive up costs.

Another widespread grievance has been the acute water shortage crisis affecting the region for many months, impacting agriculture, livestock and drinking water, and exacerbating endemic tribal fighting.

This tribal fighting, and violent criminality, have become another major source of grievance. While focus has been drawn to the war on Islamic State, cities and towns in the south have witnessed regular gun battles in the streets involving feuding tribes and criminal gangs, often resulting in innocent bystanders being killed or injured.

By June 2018, I was recording record levels of violence and protest activity across the south. There was almost one demonstration occurring every day. The failure to provide a stable supply of electricity during the extreme summer temperatures became a recurrent complaint. Then, at the start of July, Iran cut off its electricity supply to Iraq (for reasons still contested), resulting in the sudden loss of 1,400 megawatts of electricity.

Investment projects in Basra were intended to raise the province’s own energy production. However, due to the familiar problems of corruption and inefficiency, the hoped-for targets were not met and, therefore, the loss of Iranian supply became a proximate cause for the intensification of protests.

All the grievances outlined above point to two broad and interrelated failures of the post-2003 Iraqi state-building project. First, the state’s failure to monopolise the legitimate use of physical force, and second, its failure to build infrastructural power (the ability to deliver services to the population). As Toby Dodge has argued: ‘Ultimately, the stability of the state depends on the extent to which its actions are judged to be legitimate in the eyes of the majority of its citizens, and the ability of its ruling elite to foster consent.’

How will political elites respond?

Cycles of protest mobilisation have been frequent occurrences in Iraq, particularly since the so-called ‘Electricity Intifada‘ in the summer of 2010. Political elites are likely to fall back on tried and tested methods in their efforts to defuse the protests and restore order. These methods have typically involved a combination of co-optation, whereby protesters are bought off with promises of jobs and investment, and overt coercion (violence and intimidation, sometimes utilising non-state militia allies).

This strategy will be facilitated by the lack of overarching political organisation behind the protests. Elites will attempt to deal with them in a piecemeal and ad hoc fashion, deploying resources to neutralise unrest at strategic sites. For example, the Bahla protests were mediated by the Bani Mansour tribe. On 13 July, Mohammed Sabeeh al-Mansouri, a tribal leader, announced a suspension of protests at Bahla following an agreement, negotiated by the Prime Minister, the Minister for Oil, and the Basra governor, to meet some of the protesters’ demands.

However, whether this strategy can be replicated with sufficient success to defuse the protests must be in doubt. The political class now has a long history of broken promises, meaning their statements lack credibility. For example, on 12 July, an announcement by the Oil Ministry that it would create 10,000 new jobs in Basra was met with justified incredulity.

But the problem isn’t only that promises lack credibility. There is also lack of capacity to deliver them. At the heart of this problem lies the way decentralisation of service delivery from the federal government to the provinces has been implemented. This process has been uneven, chaotic, and has generated confusion about where accountability for local service provision lies.

One consultant working with the Iraqi government on its decentralisation process told me that: ‘the provinces have only really just begun the process of decentralisation, and so far, it’s been very disorganised, differing between provinces. The provinces lack the capacity and means for revenue generation, while funding to finance the directorates in the provinces still has to come from the federal government, thereby inhibiting what these directorates can really do.’

If political elites struggle to convince protesters that they can deliver on their promises they are likely to lean more heavily on overt forms of physical coercion. In 2011, then-Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki used loyalist elements in the security forces and allied militias such as Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq to intimidate demonstrators and assassinate protest leaders. The rhetoric now emerging from Da’wa Party loyalists and some of the Iranian-aligned militias bears a striking resemblance to that which preceded Maliki’s crackdown in 2011.

By way of example, Hassan Salem, a key figure in the Fatah Alliance, recently made a statement claiming that the protesters had been ‘penetrated by the Saudis and the Ba’th party’. Meanwhile, Sheikh Khalid al-Sa’idi, one of Asa’ib’s senior figures in Baghdad, delivered a threatening speech in Najaf the next day in which he stated that: ‘Any hand that reaches out to the headquarters of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq will be cut off, we will not wait to ask permission from anyone. And any tongue that dares to undermine the Islamic resistance will be silenced’.

However, it seems less likely that the Iraqi army and police would participate in a broader violent crackdown on protesters. This would mean sacrificing the credibility and affection of the Iraqi public, hard-won through their fight against Islamic State over the last few years, on behalf of the wildly unpopular political class. There are already stories emerging that suggest police and army commanders may refuse orders to use lethal violence on demonstrators.

All this leaves Iraq’s political class rapidly running out of avenues of escape. Their tried and tested tactics of co-option and coercion may well buy them some breathing space. But over the longer view, they are surely running out of options. There also remains a large degree of ambiguity surrounding Muqtada al-Sadr. The Sadrists have, by and large, avoided the wrath of the protesters so far. Muqtada remains the only major political actor with motive and means to give the demonstrations the broader political organisation they currently lack. Yet, so far, he has remained cautious. That Baghdad has not seen similarly explosive demonstrations as have been seen in the south is largely due to Muqtada’s hesitancy to throw his weight behind the protests. If this were to change, Iraq would be thrown into an even more dangerous predicament.

Benedict Robin-D’Cruz is a PhD student at the Department of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Edinburgh. His research deals with contentious politics in Iraq with a focus on the civil and Sadrist trends. He tweets at @Benrobinz

Benedict Robin-D’Cruz is a PhD student at the Department of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Edinburgh. His research deals with contentious politics in Iraq with a focus on the civil and Sadrist trends. He tweets at @Benrobinz

9 Comments