by Abdullah Al-Arian

Long suppressed by Arab regimes and kept on the margins of their societies, Islamist groups stood to benefit the most from the uprisings that have since been labelled the ‘Arab Spring’. Hendrik Kraetzchmar and Paola Rivetti’s new edited collection sketches the heterodox nature of these groups – complex actors inspired by as many intellectual, moral, cultural, political and socioeconomic commitments as any other – that was brought into focus in the wake of the uprisings.

The better part of a decade has passed since the Arab uprisings took most observers by surprise. While the region’s resurgent despotic rulers would prefer that this period be relegated to the status of historical aberration, there is little to suggest that it has ended. Nearly every country across the Middle East and North Africa continues to pursue policies directly linked to the emergence of movements of popular mobilisation since late 2010, from military interventions in neighbouring states and propping up of regional dictatorships to arming militant insurgencies and clamping down on internal dissent.

Although they did not launch the protest movements to unseat authoritarian rulers, Islamist movements were ostensibly the leading beneficiaries of the political opening offered by the uprisings. Long suppressed by these regimes and kept on the margins of their societies, Islamists nevertheless demonstrated remarkable resilience as the best organised and most deeply entrenched social force capable of providing a political alternative to a series of collapsing regimes.

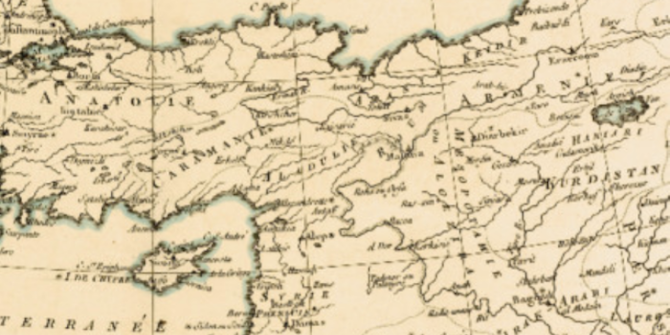

In a collection of academic papers edited by Hendrik Kraetzschmar and Paola Rivetti, a number of Middle East scholars have brought forth their findings on the impact that the Arab uprisings have had on Islamist actors. Composed of nearly two dozen chapters, Islamists and the Politics of the Arab Uprisings seeks to widen the scope of the discussions surrounding these developments. In addition to the obvious sites of popular revolt such as Egypt, Tunisia, Syria, Yemen and Bahrain, the book’s chapters also include discussion of countries not traditionally seen as part of the wave of Arab revolutions, including Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar and Iraq, along with two non-Arab regional powers in Iran and Turkey. Such topical breadth provides a far wider context to the developments under investigation, and ultimately fulfils the editors’ promise to reframe the narrative around Islamist movements.

Whereas traditional scholarship around these groups has attempted to place them on a continuum that measures their willingness to embrace democratic norms or engage in violent anti-state contention, events during the Arab uprisings would suggest that this debate is now moot. Rather, the more pressing questions would appear to revolve around how these experiences with democratic openings, aborted revolutions, and formal political organising and participation have impacted these movements ideologically and structurally. And perhaps more crucially, what can we expect from Islamist actors going forward?

For one, the flurry of developments during the Arab uprisings would confirm a long-held contention by a number of leading scholars that believe Islamist movements to be ideologically malleable, having emerged in large part as a response to particular political, socioeconomic and cultural conditions. As those conditions evolve and change, so too do the ideological programs of these movements, clear from the cases of Turkey, Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere. Mohammed Masbah makes a compelling case that Morocco’s Party of Justice and Development (PJD) has emerged as a leading exemplar of successful integration of an Islamist project within an existing state structure, even surpassing the achievements of Tunisia’s al-Nahda Party, usually held up as the preeminent model of an accommodationist Islamism. Masbah argues that Morocco’s unique context, the fragmented nature of party politics and the PJD’s pragmatism all contributed to its emergence as the leading political actor in an otherwise tenuous political structure under the ruling monarchy. Similarly, in surveying the landscape of Islamist parties in Egypt after the 2013 military coup, Barbara Zollner observes that Salafi parties exhibited a “strategic calculus” that saw them avoid the fate of the Muslim Brotherhood. Indeed, under the resurgent authoritarianism of Sisi’s Egypt, Salafi quietism represents the only acceptable form of participation.

In examining these recent struggles for political power, the old binaries such as the Islamist-secularist divide have proven unhelpful. Mariz Tadros employs such an approach in an analysis of the Freedom and Justice Party’s (FJP) inability to reach a consensus around its proposed Egyptian constitution in 2012. While it is true that the FJP was balancing internal pressures with external partnerships in devising its constitution, this was a minor plot point. In fact, the short-lived Morsi era in Egypt was defined more by actors operating either within or outside the bounds of a clumsily conceived post-authoritarian transition. The episode surrounding the passage of the constitution was more reflective of the unwillingness of some groups on the losing end of that process to abide by its terms than it was about the contents of the draft constitution. Far more problematic in the Muslim Brotherhood’s proposed constitution than its calls for Islamic law was its safeguarding the military’s immunity from civilian oversight and its reification of many of the most troubling practices that defined six decades of authoritarian rule. To reduce Egypt’s transition to an Islamist versus secularist divide would be to miss the forest for the trees.

Thankfully, that narrative is critiqued elsewhere in the volume. In several chapters, we encounter secularists adopting ideological elements of their Islamist counterparts, while Islamists appear to be shedding many of their Islamist credentials. The fact of the matter, it would appear, is that there are far too many other variables informing political preferences than narrow allegiance to religious belief. For instance, the adoption of neoliberal economic models by Islamist parties in Egypt and Turkey arises as an explanation for political failure, in the case of the former, and has resulted in the emergence an Islamist left alternative, in the case of the latter.

When faced with the challenge of having to come to power democratically, secular political parties have tended to embellish their own Islamic credentials. As Anne Wolf documents in the case of Tunisia, Nida’ Tunis, a party that includes many remnants of Tunisia’s authoritarian past, has avoided positioning itself in stark opposition to al-Nahda. Instead, it has welcomed al-Nahda’s “persistent focus on reconciliation and compromise” and even joined forces in a coalition government. For its part, al-Nahda announced in its 2016 party conference that it no longer considered itself part of the Islamist trend, instead likening itself to the Christian Democrats of Europe, a civil party inspired by religious faith. A similar (albeit far more modest) process has also shown itself to be at work in Kuwait, where what three authors refer to as “Islamist proto-parties” have increasingly begun to operate on the basis of pragmatic political calculations and worked more closely with liberal and leftist forces in the interest of a broader agenda of reform.

The book does well to situate Islamist groups more prominently within a drastically changing regional dynamic. As longstanding authoritarian regimes were weakened by the wave of revolutionary movements, the impact of Islamist actors could be felt beyond their immediate environs. Katerina Dalacoura explores this dynamic across three spheres. Hezbollah’s changing priorities as a key actor in the Syrian conflict has shifted it away from its traditional “third-worldist Islamism,” and instead helped stoke the flames of growing sectarianism. The changing fortunes of Muslim Brotherhood parties in Egypt and Tunisia has fed into the escalating tensions between Qatar and its Gulf neighbours, led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In the face of state collapse in parts of Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen, groups like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State have filled the breach, offering a violent alternative to the failures of peaceful transitions to democracy. These narratives complicate the existing picture and showcase not only the impact that the Arab uprisings have had on Islamist actors, but also how the latter continue to play a crucial role in regional relations.

Ultimately, the book avoids answering the question of whether there is some quality unique to Islamist movements that requires them to be examined within a distinct set of standards from other political actors. The movements themselves would appear to want to shed their essentialising quality, while scholars are slowly moving in that direction as well. The authors contributing here increasingly see these movements as engaged in the same processes and political behaviour as their non-religious counterparts. Jillian Schwedler’s concluding remarks offers a strong hint of the next wave of scholarship on Islamism. Invoking the concept of “Islamistness” she proposes complicating the study of these movements by exploring “degrees of association or attachment across multiple fields rather than a binary distinction between what is and is not Islamist.” In other words, Islamists are complex actors inspired by as many intellectual, moral, cultural, political and socioeconomic commitments as any other political actors. The Arab uprisings and their aftermath have merely brought that reality into focus.

Abdullah Al-Arian is an Associate Professor of History at Georgetown University in Qatar. He is the author of Answering the Call: Popular Islamic Activism in Sadat’s Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2014). He tweets at @anhistorian

Abdullah Al-Arian is an Associate Professor of History at Georgetown University in Qatar. He is the author of Answering the Call: Popular Islamic Activism in Sadat’s Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2014). He tweets at @anhistorian