by Eman Alhussein and Sara Fouad

In most societies, the boundary that separates the public from the private sphere is not fixed, but in the Saudi context, the line is even more permeable. Women’s legal standing in Saudi Arabia is the most obvious example of the state’s deep interference in the private sphere. Despite its attempt to dial down on moral policing, a willingness to refrain from heavy regulation of people’s daily choices, and its newly adopted narrative of championing women in the workforce, the state’s legal system continues to award men the power to dictate to and restrict women.

A number of laws have been designed to facilitate this. One example – widely discussed in international media – is the guardianship system. This system is the most potent demonstration of state intervention to enable and embolden male authority already present within the family unit. In other societies, the patriarchal structure is maintained, for the most part, in isolation from state interference, which makes it easier to challenge.

Maintaining and advancing the guardianship system remains very costly, but it has long been an important component of the state’s official narrative. While the old narrative championed the pious, conservative woman, the newly adopted discourse instead valorises the cosmopolitan woman. The new expectations of the modern Saudi woman have emerged while the outdated legal system remains in place, benefitting only privileged women who are not restricted by their guardians.

In line with this new narrative, a royal decree was issued in May 2017 to partially amend the guardianship system, suggesting at first glance that the government is reluctant to continue with it. In theory, the decree was meant to clarify the system’s parameters and restrict government agencies from requesting a guardian’s permission when this is not legally required. This would mean that women would only need a guardian’s permission to get married, travel, and enrol in the government’s scholarship program. Women could now seek medical help and enrol in Saudi universities without their male guardian’s approval. Implementation, however, has been slow with several women reporting that they continue to face the same old obstacles. Nonetheless, the decree was a positive step towards acknowledging the restrictiveness of the guardianship system on women. A couple of months later, many celebrated the fact that the royal decree that lifted the ban on women driving did not stipulate that a guardian’s permission was required to obtain a driving licence.

Nonetheless, the state continues to intervene in what it has itself labelled as ‘private family affairs.’ The most relevant, and most recent, example is the case of Rahaf al-Qunun (now Rahaf Mohammed). When Rahaf escaped her family, intending to seek asylum in Australia, the Saudi authorities stepped in to try to obstruct her attempt to flee. She was lucky; being offered international protection and later granted asylum in Canada. However, other Saudi women who have attempted to flee have been less fortunate. This was not the first time that the Saudi authorities’ reach extended beyond its borders to recapture women escaping abuse and restrictions to their freedom. Given the state’s renewed narrative vis-a-vis women’s rights, the question must be asked: Why, instead of following women across continents, will Saudi Arabia not address the problem at its root?

Moreover, the legal system still provides male guardians with a number of tools to exert their power. A male guardian is legally enabled to request the help of the authorities to discipline his daughter by filing a report of ‘uquq (the charge of ‘disobedience to parents’). In the past, this law has been used to recall and bring back absent daughters. A recent example – the case of a woman in Jeddah – shows the dire ramifications of maintaining this legal tool. This woman, whose name has not been made public, asked her father to issue a passport for her so she could travel abroad on a scholarship. Her father, who was against her decision to travel, not only rejected her request, but also filed an ‘uquq case against her.

A man is also legally enabled to recapture his female relative with the help of the state by filing a taghayub (absence) case. It is not common for Saudi women (or men for that matter) who are unmarried to move out of their parents’ home. Some of those who have attempted to do so in the past were victims of abuse, threats of abuse, or further restrictions. The taghayub law makes it impossible for women to start a new life in Saudi Arabia away from their family, regardless of whether the family is abusive. Means for protection from abuse remain very limited, which is why a significant number of women choose to flee the country when faced with abuse at home. Upon discovering her escape, Rahaf Mohammed’s family would have used one of these legal tools in their attempt to recapture her.

Marriage and divorce remain largely controlled by the legal guardian. The legal system does provide for divorce on the grounds of a perceived ‘lack of compatibility,’ be this religious or tribal. Even though a woman is legally able to contest her family’s refusal to marry her off to her preferred suitor, she can be obstructed at a later stage if her family file a ‘lack of compatibility’ case. In the face of the myriad avenues men can use to reclaim their female relatives, women have limited, and often futile, options to counter their guardians. The legal system maintains and awards men unchallenged authority over women.

While in cases like Rahaf’s the state has intervened in what it has itself labelled a ‘private family affair’, on other such affairs it has been reluctant to take action. Women who face abuse at home are given limited protection. The Saudi Law of Protection from Abuse criminalises domestic abuse, and a helpline has been set up to report domestic abuse cases. However, many have reported that the helpline is not always helpful. As such, women tend to resort to social media to generate public sympathy and support, which usually pushes the authorities to respond to their cases. Subsequently, women subject to serious physical abuse may be taken into ‘safe houses’ or ‘care centres.’ However, most of the cases that went viral and ended with the abused seeking help through a protection centre never make it back to social media, adding to the skepticism around how such centres tackle abuse. Moreover, even though protection centres are for women who are victims of abuse, they still cannot leave without their male guardians. The only way for an abused woman to leave the centre is to find a husband she can marry, or attempt to solve the problem with her male guardian.

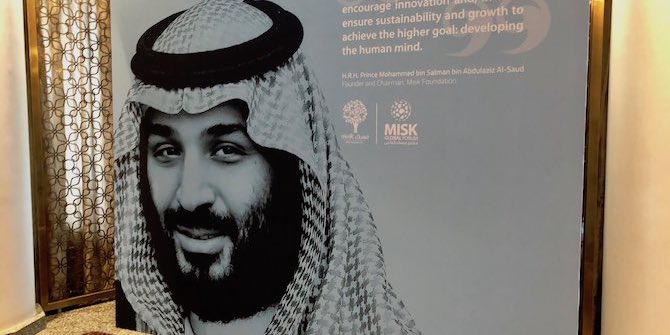

The Saudi legal system remains suffused with patriarchal strictures justified under the guise of ‘family values.’ In his interview with The Atlantic, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman expressed a desire to change the guardianship system in a way ‘that doesn’t harm families and doesn’t harm the [Saudi] culture.’ If the intention were to slowly dismantle the guardianship system in a way that did not harm the family structure, the way forward would be to first abolish the disobedience and absence laws. In September 2018, Shura Council member Eqbal Darandari recommended that the Ministry of Justice stop accepting ‘uquq and taghayub applications, but this was rejected by the members of the council. Despite public pronouncements, heavy government intervention in regulating the family unit is unlikely to wither away anytime soon, so long as the state remains adamant on maintaining the legal tools that facilitate these patriarchal practices.

2 Comments