by Deepika Saraswat

The most recent wave of anti-government protests in Iraq have left over four hundred dead since the beginning of October. The deaths have been blamed on the Iranian-backed Shi’a Hashd al-Sha’abi (Popular Mobilisation Forces) paramilitaries, which played a vital part in the fight against ISIS and are in the process of being assimilated into the Iraqi army. The militia leaders consider the leaderless popular protests – which demand the resignation of the Prime Minister Ali Abdul-Mahdi’s government and the complete overhaul of the political system – as engaged in a ‘coup d’etat’ or rebellion, resonating with the view of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who argued that ‘their people (Iraqis) have to know that although they have legitimate demands, those demands can be met only through the framework of legal structures.’ Iran has furthermore reportedly intervened to forestall the fall of the Iraqi government by asking Hadi al-Amiri, the leader of the Badr Organisation (whose alliance secured the second highest number of seats in last year’s parliamentary elections) to stand with the beleaguered prime minister.

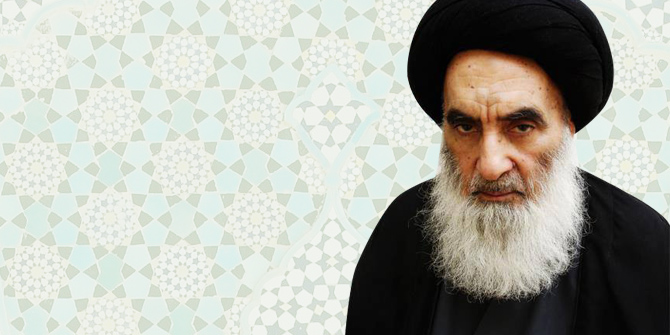

But as the violence escalated, Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the marjaiyya (source of religious emulation) for majority of Iraq’s Shi’ite population, warned of civil war. In the Friday sermon released by his office on 29 November 2019, Sistani said that the government ‘appears to have been unable to deal with events of the past two months’ and called on lawmakers to ‘reconsider’ their support for the current government. Subsequently, Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi tendered his resignation, which was accepted by the Iraqi parliament. Ayatollah Sistani has supported protesters’ demands for replacing Abdul-Mahdi’s government with a government that will hold those responsible for the deaths, draft new electoral legislation, and form an independent election commission which will conduct an early parliamentary election under international monitoring. The sustained mobilisation at Baghdad’s Tahrir Square and other cities in the Shi’a-dominated south is a powerful indication that Iraq’s Shi’a majority, having suffered under years of poor governance, has lost faith in the ruling Shi’a political parties.

Structural Crisis of the Post-Saddam Iraqi state

Saddam Hussein’s Ba’thist state adhered to the typical Arab socialist model, where the authoritarian regime, taking a nationalist-populist line, maintained a significant economic and social welfare state which gave it a strong social base among peasants, workers and the middle class, but did not allow the political space for civil society to develop. Iraq’s transition to democracy, engineered from above by the US-led invasion which removed Saddam Hussein from power in 2003, was therefore dominated by opposition exiles in Iran, Syria and Europe.

Lacking an organisational base and constituencies inside Iraq, these parties organised their politics along primordial ethnic and religious lines and the new Iraqi polity came to be founded on the basis of a power-sharing ethno-sectarian formula geared towards maintaining ‘balance’ between different communities. The arrangement has not only precluded the development of coherent and rational state institutions by causing the fragmentation of political space and enabling external influence in Iraq’s domestic political processes, but is also blamed by many ordinary Iraqis for the erosion of their national identity.

The US policy of supporting personalities in Iraq, rather than pursuing good governance and the institutions of government, is also blamed for the crisis that faces the post-Saddam and post-ISIS Iraqi state. In 2012 the US continued to back the then-Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, despite the Iraqi parliament bringing a no-confidence vote against him for his ‘autocratic decision making’ and interference with the functioning of parliament and security forces while sidelining the Sunni and Kurdish communities.

Iran is also blamed by Iraqis for cultivating Shi’a parties and militias as vehicles of strategic and ideological influence in the country. Iran-funded and trained Hashd al-Sha’abi paramilitaries have undermined the role of Iraqi security and police forces, which continue to be trained by NATO missions in the country.

From Islamism to Reform Populism

In early 2014, ISIS took Fallujah, 40 miles to the west of Baghdad, and the Iran-backed Shi’a Da’wa Party Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki projected himself as the leader of the Shi’a community under attack from Sunni extremists. Subsequently, Muqtada al-Sadr, the leader of the Sadrist movement representing the Shi’a underclass – who had until 2010 engaged in the anti-American insurgency with assistance from Iran, and supported Iran’s theocratic velayat-e-faqih (Ruleof the Jurist) system – announced his withdrawal from active politics and launched a frontal attack against Iraq’s corrupt, sectarian political elite. His year-long sit-ins (2015-16) in Baghdad’s Green Zone focussed on popular demands: reforms, better public services and an end to corruption. The protest movement was secular and nationalist in orientation and saw active participation from communists and civic groups, who later became part of the cross-sectarian Sairoon (translating as ‘Marching’ [towards reform]) alliance that went on to win the highest number of seats in the May 2018 parliamentary elections.

In early 2019, when negotiations to form a government went on for months after the elections, massive popular protests erupted in the largely Shi’a Basra-Amara-Nasiriyah triangle, demanding better services and jobs. The violent attacks on political party offices and provincial council buildings exposed the crisis of legitimacy of the Shi’a Islamist parties which had ruled Iraq for the past sixteen years. The most common slogans in these flag-waving protests were ‘No, no to political parties’ and ‘corruption is terrorism.’

The ongoing leaderless protests have received support from both al-Sadr and Ayatollah Sistani, the two most prominent leaders not directly involved in Iraqi politics. From calling for an elected constitutional assembly in 2004 to demanding the authorities deal seriously with the demands of citizens during last year’s protests, Sistani remains the most influential voice of the people-driven democratic process in Iraq. In a statement issued by Sistani’s office after his meeting with the chief of the UN Assistance Mission to Iraq, he raised doubts over the seriousness of authorities in enacting real reforms and called on Iraqis not to leave Tahrir Square until their demands were met. Any serious reform of the ethno-sectarian power sharing political arrangement will undoubtedly be resisted by the entrenched Shi’a and Kurdish elites and their external backers, further ensuring that popular protests are set to become an entrenched fixture in Iraqi politics.