by Tom Ready

A new wave of popular unrest across the Arab world has triggered claims of a second Arab Spring. The truth is that the first Arab Spring is still being played out and the underlying grievances have not changed.

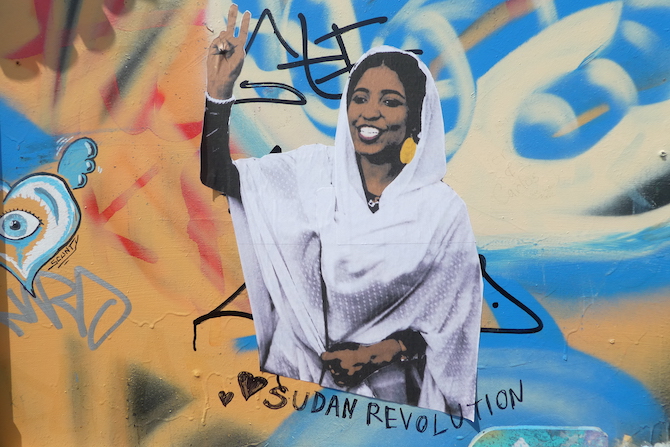

At a state level, with a few notable exceptions, the political landscape of the Arab world might be characterised as follows: a core of monarchies which has thus far survived the turbulence of the Arab Spring (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Jordan, Morocco); a scattering of democracies of different hues, governed by political elites struggling to maintain trust and legitimacy in the face of a re-invigorated wave of popular protest (Lebanon, Algeria, Tunisia); and four cases of catastrophic state failure accompanied by massive foreign military intervention (Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen). The exceptions are Egypt, under the control of a military strongman following a 2014 counter-revolution which reversed the country’s democratic gains; Sudan, where protests in 2019 led to the removal of President Omar Al-Bashir and the appointment of a transitional administration; and the Palestinian territories, for their own distinct reasons. All this against the backdrop of a US-backed alliance (led by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel) which is dramatically failing to curb Iran’s expanding sphere of influence across the region.

Any attempt to disentangle the region’s immensely complex political and socio-economic crisis must, however, quickly dispense with a reductive national framework. Firstly, the underlying forces which are contributing to the current wave of popular mobilisation on the streets of Beirut, Basra, Annaba and Jelma, share many things in common, despite their local idiosyncrasies: youthful populations suffering from rampant unemployment; anger at corrupt and repressive political elites; and perceptions of sinister foreign agendas. Secondly, the protests and anger are feeding off each other, united by language and fortified by social media and belief in change. And thirdly, the trajectories of these crises are beholden to the wider regional and global order, with external economic and military aid to internal actors contingent on foreign policy alignment or other quid pro quos.

A generational rebellion

Whereas in 2011, the protestors may have placed their faith in opposition leaders or the military to bring about change, the current wave of protests reflects a total mistrust of incumbent elites. Nowhere is this more evident than in Lebanon, where a largely peaceful youth protest movement is united by cross-confessional and cross-societal solidarity. The demonstrations were triggered in mid-October by tax proposals on mobile messaging platforms, but are rooted in broader anger against austerity, corruption, economic malaise, high prices, and the absence of basic services. There is also a distinct anti-Iranian character to the marches and sit-ins, with the political stock of Hezbollah, backed by Iran, having fallen precipitously from its 2000 high, when it forced Israel’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon. Anti-Iranian sentiment is also a key driving factor of the bloodier unrest in Iraq, where in late November, protestors stormed and torched the Iranian consulate in Najaf. 460 protesters have reportedly been killed in the past two months. Like Lebanon, there is broader anger against entrenched identity politics, and the system of muhasasa, whereby government spoils are divided along sectarian lines.

In North Africa, thousands of Algerians have been taking to the streets since February 2019 in a strikingly under-reported wave of protest. This succeeded in forcing the resignation of President Bouteflika in April, but has done little to reduce the trust deficit between the people and the political and military elite. In neighbouring Tunisia, the fragile democracy which replaced President Zein al-Abidine Ben Ali in 2011 also faces the continuing threat of old regime patronage networks. Large-scale protests have been ongoing since January 2018 and have witnessed a recent upsurge. A lapse back into heavy-handed security tactics is becoming more likely, while the playing out of rivalries by Gulf states, through investment and direct financial support, threatens internal stability and foreign policy independence.

Hardening regimes

While democratic gains in Tunisia since 2011 have rightly been celebrated, these remain an anomaly in the region as a whole, which has experienced increased political repression and state-sanctioned violence. In Egypt, the security and intelligence services of the Mubarak era enjoy an even freer license under President Al-Sisi. In Saudi Arabia, the shadows of the 2017 arrest of hundreds of wealthy and influential Saudis at the Ritz Carlton and the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 continue to loom large over Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s attempt to radically reshape the social, economic and cultural fabric of the Kingdom, but without any accompanying political freedoms.

Meanwhile, the ongoing civil wars in Syria, Libya, and Yemen have destroyed any hope of functioning or representative political structures in these countries. The withdrawal of the United States from these arenas as a broker of peace and transition, coupled with a blinkered focus on defeating ISIS, has led to Russia taking the lead as a regional power-broker, and the thickening of Russian ties with key regional actors (Turkey, a member of NATO, has just taken receipt of a Russian missile system). Other traditional US allies such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE continue to pursue regional agendas with or without US consent, a departure from an earlier paradigm. The looting and kleptocracy will continue in these warzones, with no external accountability.

The political structures of the remaining Arab monarchies – Morocco, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and Oman – have remained intact. All have felt, to differing degrees, the effects of the Arab Spring and have made modest adjustments to navigate situations of more acute popular pressure. Yet to date no Arab royal has been toppled, despite predictions to the contrary. There is no simple explanation, but historical legitimacy is probably one key factor, to the extent that in most cases, there is an inextricable link between the ruling families and the birth of these states out of colonialism. In addition, the oil-rich sheikhdoms have relatively smaller populations which are closely tied to state institutions and share in the benefits of stability. Thirdly, despite tensions between the wealthier Gulf monarchies, notably the regional isolation of Qatar by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, it is not in anyone’s interest to rock the boat too much. Better to play out these rivalries in other places.

Into 2020

It is misleading to argue that the current protests represent a second Arab Spring. The first one is still ongoing and the underlying systemic grievances – youth unemployment, political disenfranchisement, rampant corruption, and foreign interference – are not seasonal, but endemic to the region. In 2020, the protests will continue, where they can, but in most places, the deep state structures and the interests they guard will continue to fight back, protected by external backers.

This piece is an edited version of a longer article published by Aperio Intelligence, available here.