by Jassim Al Awadhi and Geoffrey Martin

The bus system is vitally important for many people living in Kuwait. Total annual passengers on legally operated buses are estimated at close to 120 million. This figure represents approximately 122 trips per 1,000 persons per day.

The most recent Kuwait Public Transport Master Plan (KPTMP) identifies many challenges that will impact Public Transportation (PT). Simply put, Kuwait’s total population (including expatriates and nationals) is projected to increase from 3.4 million to 5.4 million by 2030. The highway network conditions are forecast to deteriorate, and congestion is expected to increase even taking into account the large number of highways being improved, built or planned. Much of the forecasting for PT is conditional on the successful completion of the New Towns and population growth in those locations. PT planning is wrongly predicated on the idea that the 60 percent increase in population will all be centred in North Mutlaa, Sabah Al-Ahmed City and the new suburbs around Silk City. We cannot be sure of these assumption, or the success of any of these housing plans, as historically they have been a failure and the housing crisis continues to be one of the biggest infrastructural problems Kuwait faces.

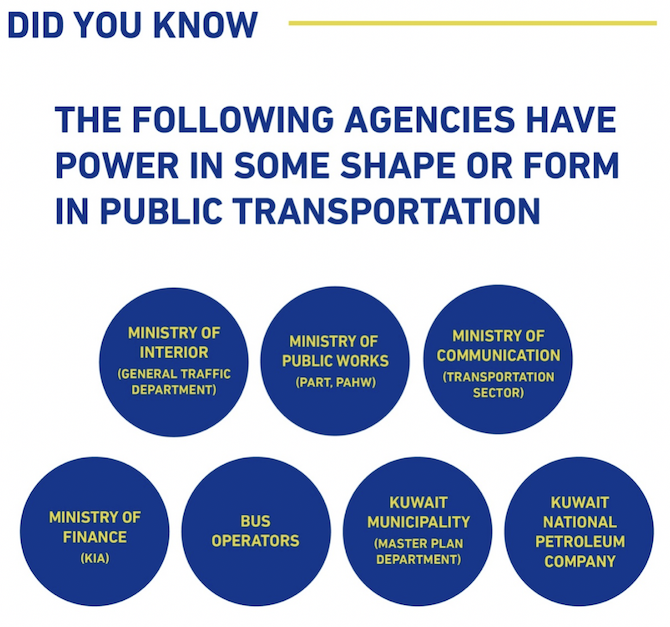

PT policy and oversight is mired in bureaucracy and stakeholders lack the political will to change the current trajectory – towards a demographic disaster. There are at least 15 major government organisations and institutions involved in transport planning: see the major policy makers in the diagram below.

A politically powerful public transport, with a government-backed plan – combining transport policy and regulation of the private sector is essential to implement sound PT policy. In 2014, Law No. 2014/115 created the Public Authority for Roads and Land Transportation (PART). From a legal perspective, the development of the PART laws was a major step forward to developing a single mass transit authority (see full report here). But because of the institutional infighting in PT, PART is stunted, to the point that it does not operate in 80–90 percent of its legislative mandate. Governance continues to be diffused to more actors. For example, PT plans for new residential areas developed as part of Kuwait 2035 are going to be governed by the Public Authority for Housing and Welfare instead of PART.

Kuwait’s PT is a good example of how neo-liberal policies do not work when connected with public good. In practice the bus system in Kuwait is run as if it is a private sector business. City Bus and Kuwait Gulf Link (KGL) became service providers in 2003 and 2006. The initial hope was that having ‘competition’ would further develop the sector, improve overall performance, and further decrease the government’s involvement. But because bus operators in Kuwait are left to provide their own ‘laissez faire’ approach to providing information to their customers there isn’t any concrete information. As the KPTMP admits, the ‘lack of clarity makes understanding how the public transport network operates and connects Kuwait almost impossible to comprehend’.

Facilities at bus stops and stations are generally poor, as is pedestrian access and associated road crossings. Kuwait Public Transport Company (KPTC), the government PT carrier, erects their own bus stop poles and flags (there are only 1,700 of these); the other two private operators City Bus and Kuwait Gulf Link (KGL) also provide their own, leaving three adjacent poles. Bus shelters (also provided by KPTC) are at many stops, although these are generally in a poor state of repair.

Access to stops is also an issue. This problem has multiple dimensions: the sheer distance, difficulty in crossing highways, disintegrating footways, and poor lighting. It often can be quite an adventure getting to or finding a stop if you don’t know the area. Bus routes are also overly focused on Kuwait City as the destination point, disregarding other important locations, including government buildings, hospitals, newer commercial areas, tourist sites, and neighbourhoods that sit on the horizontal axis of the city above 3rd Ring Road.

Instead of efficiency, privatisation has actually led to more congestion as private providers only run on profitable routes, making for stiff competition between the three services. There are 43 routes operating currently, yet around 50 percent of total buses are dedicated to nine routes which carry 58 percent of all passengers in Kuwait. Traffic bottlenecks, such as the Jahra Gate Roundabout in Hassawi on Road 175 northbound, lead to huge and unnecessary delays.

The consequences of poor planning are stark. Both of us have taken the bus hundreds of times throughout the city and outlying areas. Huge delays are common. For example, it often takes 40–50 minutes to take a trip from Granada to the main transfer station in Maliya, a distance of only two kilometres. A 20–30 km trip from Mahboula to Salmiya can take up to 2 hours during commutes.

From our conversations from a wide variety of stakeholders, it is apparent that the main issue remains a lack of political will to change PT policy. This is largely because the government and its agencies do not know what people want. A major requirement of the recent KPTMP was to develop a comprehensive understanding of public opinion. Unfortunately attempts to gather survey data have been very poor or non-existent. To date there has never been a representative survey of people who take the bus.

From our observations a large segment of expatriates and Kuwaiti nationals (especially the younger generation) want to use the bus but don’t know how. At presentations KC gave at the American University of Kuwait, many of the students’ present were shocked to find that approximately 80 percent of their peers had never used the bus in Kuwait, although all used public transport outside of the country, especially in Europe and North America.

The good news is that the public is open to using buses, but for them to be able to do that the government needs to give them a voice. With the right amount of political weight, by raising awareness and engaging officials, this can be done. We hope to lobby to foster the political will to change this by engaging with stakeholders both in the private and government sectors. But most importantly we want to focus on people, so often left out of these conversations.