by Benedict Robin-D’Cruz

On 19 August, Riham Yacoub was executed by gunmen in central Basra. Riham was 30 years old; a graduate in sports science who ran a women’s health and fitness centre in Basra. Since her death, Riham has frequently been described as one of Basra’s leading protest activists. A video has even circulated widely on social media claiming to show Riham leading protesters in chants during recent demonstrations in the province. However, this video is fake. The women it shows is not Riham and the protest is not in Basra. In reality, Riham was not a protest leader nor a political activist. She had withdrawn from participation in the protests after 2018, and she was never a leading protest organiser prior to this. So why was she assassinated?

The US Consulate Conspiracy

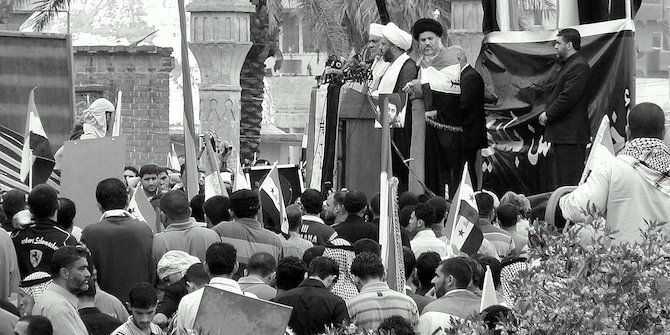

I first contacted Riham in the summer of 2018. Her name, along with several other young Basrawis, had got caught up in a controversy surrounding the US Consulate in Basra. A conspiracy theory – initiated by Iranian state news agency Mehr – was circulating in Iraq, accusing a group of young people who participated in the Iraqi Young Leaders Exchange Program (IYLEP, funded by the US Embassy in Baghdad) of being agents in a US plot to orchestrate violent protests in Basra. This was mid-September 2018, approximately a week after protesters in Basra had burned down the Iranian consulate building in the province (along with many offices belonging to Iraqi political parties and armed groups).

The young Basrawis accused by Mehr were not US agents. In fact, most of them were not even involved in the protests. Another of the agency’s targets, a university student, told me how he was woken at one in the morning by a barrage of messages on his social media accounts:

‘I was accused of starting all the protests that took place in Basra, that I was the master mind of all the chaos that was happening… It was very ironic because all those claims were completely false. First of all, I was preparing for my exams, and secondly, I never knew anything about politics and don’t even talk about or discuss it!’

This young man, an aspiring vlogger, was forced to flee Basra altogether and still resides outside Iraq to this day. Why was he targeted? He told me: ‘The militias can eliminate people, just like that, just because they’re different and productive people who try to make a difference in their own world’.

Riham’s own involvement in the protests was slight. She told me that she took part in some of the demonstrations in 2018 and had encouraged a few dozen women to join the marches with her. A photo she had taken of herself with these female protesters was used by Mehr, along with photos featuring Riham published by IYLEP, to construct their conspiracy by connecting the protests to Riham and Riham to the other participants in the IYLEP program. This was picked up by Iran-aligned political groups in Iraq and circulated widely. Riham was clearly scared: ‘I was threatened from unknown sources, there was incitement to kill me. My pictures spread everywhere.’ Riham told me that her name had been placed on a monitoring list held by security forces in Basra.

Riham’s family were ultimately able to intervene on her behalf and to have her name removed from the list (or so it seemed). In return, Riham withdrew from protest activity. This sort of negotiation has been fairly common in Basra. When an activist is threatened by an armed group and their name put on a monitoring or assassination list, they are sometimes able to draw on tribal networks to intercede on their behalf. Riham’s family are part of Basra’s powerful Imara tribe (concentrated particularly around the Madaina area in northern Basra), and although she never told me explicitly, my assumption was that a tribal intervention had temporarily smoothed over the controversy.

Who is being Killed in Basra and Why?

Although Riham was not an activist leader in the protests, her social background fits the profile of most of the activists targeted for assassination (three activists have been targeted in Basra since 14 August alone, not including Riham). These individuals tend to be slightly older than many of the protesting youths (typically in their mid-to-late 20s or 30s), come from middle-class families, are university educated and in employment, and are disproportionately female.[1]

This is not the social profile of the young men whose recent protests in Basra have involved violent clashes with ISF and petrol bombs thrown at police vehicles, Iraqi police members and government buildings. Yet these protesters, involved in the chaotic violence seen in Basra particularly in the summer of 2018, are not targeted by armed groups for assassination. Why?

The reason is that these young men are mostly Sadrist youths from Basra’s poor neighbourhoods such as Hayy al-Hussein, Khamsa Meel and Tamimiya. Consequently, they are more economically desperate and easier to buy off with promises of jobs or money.[2] This means that, despite their propensity for violence, this group is more containable and less threatening to the political system. Their violence may even partly serve the interests of political factions who want to portray the protest movement as a whole as ‘anarchic’ and destructive.

Moreover, these young men typically belong to families that are both tribally engaged (meaning their tribal networks are more active), and to have brothers, uncles and cousins involved in different PMF or other armed groups. Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq cannot send assassins into Khamsa Meel to kill a Sadrist youth without repercussions.[3]

By contrast, the activists whose social profile matches Riham’s have been at the forefront of attempts to steer Basra’s protest movement toward more peaceful channels. They have also sought to elevate its demands from transactional claims for jobs or better local services, into a more political movement focused on calls for systemic political reform.

It is this latter aspect, and particularly the potential role they could play in turning the protests into a new political platform to compete in Iraq’s national elections (tentatively scheduled for June 2021), that makes these activists a threat. And while this threat makes them a target for violence, they also lack a coercive shield or deterrence. They are less likely to have strong networks that tie them to PMF and other armed groups, and their families are likely to be less tribally engaged. For instance, Riham’s father, a retired navy captain, has told local media following his daughter’s killing, that he does not want vengeance, but the justice promised to him personally by Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi – the justice of the Iraqi state.

Why Did They Kill Riham?

Riham was not a political organiser. So why was she killed? For Iraq’s armed groups, and their patrons in Iran’s intelligence apparatus, the fact that Riham was a high-profile female voice in local civil society activism was reason enough. It is not only political action that threatens these groups. They also cannot tolerate Iraqi youth who are determined to reject their system of violence and corruption and to strive to create a way of life for themselves beyond the militias’ reach.

However, it should also be noted that Riham came from a similar social milieu to the more politically active protest organisers. Consequently, her killing sends an impactful message to this group, a warning that anyone who gains prominence and becomes a symbol around which resistance can be organised, risks assassination. This is a stark message ahead of the planned elections in June.

Many activists who may have been preparing the ground for the protest movement’s first political steps have now gone underground. Riham’s killing also reminds activists that the armed groups have long memories, and that once your name goes on the list, it can never truly be removed, and death could come at any moment.

Finally, Riham’s assassination was clearly timed to coincide with Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s trip the US to discuss the future of US-Iraqi relations. Her superficial and largely fabricated interactions with the US consulate tied together the narrative of the assassination from the perspective of those seeking to undermine US-Iraq relations. This strongly suggests direct involvement from the Iranian IRGC. In this sense, like the assassination of Hisham al-Hashimi in Baghdad in July, Riham’s murder looks like a personal challenge to the Iraqi Prime Minister and his authority.

The Prime Minister appeared to draw the same conclusion, returning from the US and heading straight to Basra to oversee the response of the province’s security apparatus to the recent killings. Kadhimi also visited Riham’s family where he promised them justice that many doubt he can deliver.

The Conflict Research Programme–Iraq’s project ‘After the Uprising: Post-Mobilisation Strategies in Southern Iraq‘, led by Principal Investigator Benedict Robin-D’Cruz, explores the tactical choices and broad strategic debates between different protest groups in the region.

[1] Disproportionate when considered against the size of female participation in Basra’s protest movement.

[2] In one recent case, a young man active in Basra’s protests was arrested during a violent demonstration. Governor Assad al-Idani met with the youth in a televised recording at Basra Police HQ. He reminded the youth that he had previously obtained jobs for him and some of his friends who had been protesting earlier in the year. However, the youth revealed he had sold the job for cash in order to buy a taxi. In the end, the young protester was released and Idani pledged to build his family a new home. The youth was later filmed returning home to family and praising Idani’s generosity.

[3] It is worth recalling here the incident in Maysan following the outbreak of protests in October 2019, in which Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq militiamen opened fire on protesters at one of their offices, only to come under direct fire from Sadrist paramilitaries, resulting in one death and several injures to AAH gunmen.

FYI

Translation of this article into Arabic

https://iraqicp.com/index.php/sections/platform/44374-2020-10-25-08-40-10

With my compliments