by Tan Feng Qin

Sociologist Kevan Harris once noted an ‘inordinate emphasis on the strange and scary’ in existing studies on Iran. In July 2020, attention was focused on a spate of fires and explosions in Iran that appeared to some too meaningful to be coincidence. The visual inspection of an Iranian Mahan Air passenger airliner by an American F-15 jet, and Iran’s ‘Great Prophet 14’ naval exercise soon after, kept public attention on the precariousness of a situation in which Iran seemed to be under constant pressure to react. The American seizure of petrol cargoes meant for Venezuela, the insistence on extending the UN arms embargo on Iran indefinitely, and now the US effort to declare a ‘snapback’ of UN sanctions on Iran keep alive residual worries that Iran will react adversely to provocation. As this piece is written, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director General Rafael Grossi has just concluded a visit to Iran, where he secured an agreement for access by inspectors to two sites of interest to concerns over Iran’s prior nuclear activities, averting – for the moment – a confrontation. Will continued external pressure on Iran, together with domestic pressure from hardliners, cause Iranian decision-makers to slip at the last hurdle and destroy the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal mere months before the US presidential elections?

Attention in July had been most focused on the incident at the advanced centrifuge assembly centre at Natanz, and the incident helps us to understand what has been happening and how Iran might respond. There has been extensive discussion about the possibility of sabotage at Natanz. While Iranian officials have offered ordinary explanations for many of the incidents in July, on Natanz they declined to announce the cause, citing ‘security concerns’. A spokesperson for the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran has now declared the incident sabotage. At the time, anonymous Middle Eastern security officials asserted to the press that it was Israel, at Natanz, with a bomb.

What might have been the strategic rationale for a bombing at Natanz? One view at the time offered that the attack was meant mainly to set Iran’s nuclear programme back, causing damage to the development and mass production of advanced centrifuges that might take two years to recover from. Analysts had noted such an attack seemed short-sighted and unwise, and could push Iran’s enrichment efforts underground or reduce its willingness to cooperate with the IAEA.

As events have since made clear, an alternative reading is the Natanz incident, though it damaged Iran’s centrifuge development efforts, was meant mainly to accomplish a number of other political goals, chiefly, to entice Iran into presenting itself as a threat. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has argued that Iran presents a threat to the region, and to Europe. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asserts that Iran is on a ‘march to the bomb’. Seen thusly, the possibility that Iran might react to Natanz by surreptitiously moving nuclear activities underground or reducing nuclear cooperation was precisely the point.

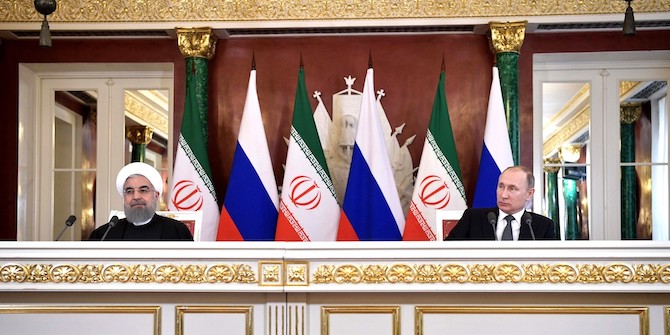

The Natanz incident, and various actions taken by the Trump administration since, present Iran with a dilemma. The pragmatist Rouhani administration risks looking weak before electorally resurgent conservatives and hardliners, who may be tempted to pounce on any perceived misstep. None of the various responses it was feared Iran would take at the time, and which it is feared Iran might still take if provoked – whether a retaliatory attack, a further erosion of JCPOA commitments, reduced cooperation with the IAEA on inspections, or a withdrawal from voluntarily implementing the Additional Protocol or from the Non-Proliferation Treaty – serves Iranian strategic interests (to preserve the JCPOA to retrieve needed sanctions relief) in the lead up to the US presidential elections in November, where polling indicates President Trump is on the back foot and could lose. Instead, such moves will only buttress arguments that Iran is a threat or is clandestinely moving towards a bomb, and risk the diplomatic cooperation of the international community, which has by and large refused to recognise the US effort at snapback.

Iranian decision makers are cognisant of the dilemma and have taken steps to avoid it. Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi has warned against taking actions that present Iran as a security threat, as have Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and President Rouhani, arguing that doing so advances American objectives. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has also intervened to reset relations between Iran’s executive and legislative branches after hostile questioning of Zarif in Iran’s new conservative-dominated parliament.

Although there was concern that Iran would react adversely to the IAEA Board of Governor’s resolution calling for Iran to offer access to the two sites, Iran did not escalate the issue beyond formally triggering the JCPOA’s dispute resolution mechanism, and now IAEA Director General Grossi’s successful visit is a cautiously optimistic sign that Iran could continue to seek an accommodation with the IAEA on future access issues, so long as the process respects Iran’s concerns about being treated fairly, and recognises the cooperation Iran has provided thus far. Iran has also signed a defence agreement with Syria that seeks to bolster Syrian air defences, a move that raises costs for Israel’s pursuit of its interests in Syria without appearing overly aggressive.

These events all suggest that, despite a proposal to introduce in Iran’s parliament an automatic withdrawal from the JCPOA in the event of a UN sanctions snapback, Iran could avoid escalating tensions further before it becomes clear whether the JCPOA dispute can be resolved, even as it seeks to hold fast to a posture of resistance. The ‘Great Prophet 14’ naval exercise in July allowed Iran to communicate a determination to resist its opponents, while avoiding the sharpness of an actual harassment of US Navy ships, as had occurred in April. Iran’s position that the fuel seized by the US did not belong to Iran, having already been sold, while reiterating it would not tolerate hostile actions, is another example of this approach.

Iran’s parliamentary speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf has decided to focus his efforts on economic issues. Although the coalition of conservatives and hardliners won resounding control of Iran’s parliament in February’s elections, the election nevertheless showed them on precarious ground, with the lowest-ever turnout for parliamentary elections in the Islamic Republic’s history. With their votes received in 2020, of the coalition’s 30 MPs in Tehran, only Ghalibaf would have been elected in 2016, a year of enthusiasm for the pragmatist-reformist coalition.

Inflationary pressures, and a difficult economic situation at a time of a world-wide pandemic continue to weigh on Iranians. The political and electoral future of conservatives, and the electoral legitimacy of the Islamic Republic, lie in resolving Iran’s economic challenges, a task that will greatly be aided by the lifting of US sanctions affecting Iran’s access to the global banking system. Khamenei’s comment that Iran will use the opportunity provided by the good decisions of others (including, perhaps, a potential Biden administration), suggests that Iran will seek to preserve a path to return to its commitments under the JCPOA under that eventuality.

In the longer term, Iranian decision-makers will have to address international and regional concerns about Iranian strategic and foreign policy to provide a stable environment for Iran’s economic development. The provision of access to the two nuclear sites is indeed a good start, and will help to defuse concerns about a current nuclear weapons ambition, even if it should raise uncomfortable issues about Iran’s past. With Iran but one potential economic partner in the region for China, longer-term economic ties with China would also be facilitated by improved relations with Iran’s Gulf neighbours, which will have to start by taking their threat perceptions seriously. It continues to be in the interests of all parties in the Iranian political system to not be distracted, in the lead-up to November, by the scary and the strange.