by Cathy Nicholson

Can genuine dialogue shift the personal and structural machinery that underlies the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? Social Psychologist Dr Cathy Nicholson (LSE) draws on her own research into the dialogical nature of conflict to show how it can be used to understand the social reality, suffering and the ongoing patterns that impact everyone involved in the conflict.

Yet again, the volcanic Israeli-Palestinian conflict has erupted into a violent struggle between the two peoples, each blaming the other for its inception and cyclical deadly manoeuvres. How many times have we witnessed the fallout, the escalating tit-for-tat fighting, the call for the international community to find a compromise to enable a ceasefire? Amid the dimming prospect of a long-term peace agreement, the international community looks on in despair. The area has more than just geo-political significance, occupying a role within the global psyche due to its association with three deeply held religious belief systems, each having played a major role in fundamental areas of societal development and impacting many facets of civilian, spiritual and political life.

As social and political psychologists we can offer the possibility of an observant eye, exploring the relationship between individuals set within a particular cultural and political milieu. And as members of the international community (without the lived experience of their suffering alongside an acceptance of our own ideological, prejudiced and utopian foundations) we do stand with compassion for human dignity and the possibility of mutual dialogue as a starting point for any global discussion.

The conflict has been described as intractable, set within an ethos of strife affecting multiple layers of personal, cultural and social life. Each group becomes unable to extricate themselves to a position of greater neutrality as the cost of retracting is greater than the cost of remaining in the situation where compromise and concessions play no part in the drive for the adherence to its original goals. And so the lived experience of conflict becomes central to the lives of its citizens where multi-media, political leadership and social institutions all play a role in its prolonged continuation. Social and semantic barriers stand to stop any valid connection with the other, leading to an entrenched stand-off. Individual and collective identities, born from individual and collective memories and perpetuated by myths, and act to reinforce the hardening of group boundaries. All of these attributes form the bedrock of social representations that define their realities, so even in times of relative peace, each group can remain stubbornly shut to the social reality of the other.

The amount of research conducted into this conflict demonstrates the extent to which it holds such a prominent position for its conclusion. Yet what tends to remain ignored by those to whom the research addresses, is the asymmetrical nature of the struggle. This was never a battle between two equal entities. One side holds the power, the increasing military might, the global influence and the societal belief in the righteousness of their goals. The weaker side remains depleted and powerless, with no legal sovereignty from which to start a possible productive dialogue with the backing of the international community. Instead the only option, when pushed to the edge of provocation, is opening the door to fighting back with whatever means they might have at their disposal as militant hardliners enter the fray. This has been shown time and time again to inflame such a delicate balance across the asymmetry, resulting in the ‘self defence’ rhetoric that inevitably leads to more intergroup aggression that fills our global news outlets. This process is easily perpetuated by the US, who through their diplomatic efforts appear to have become immobile in taking any neutral stance by supporting the stronger side with what seems to be an unconditional allegiance. Yet only the stronger side appears to have the ‘self defence’ privilege. The cry of the weaker side can become ignored, even as more and more street protests around the world march and shout the cries of injustice on their behalf. Each side mourns the deaths of their loved ones. The death toll and destruction of the infrastructure is always far greater for the weaker side, the Palestinians, than for the Jewish Israelis, though each and every killing and serious injury represents a monument of human failure. Suffering for all is guaranteed.

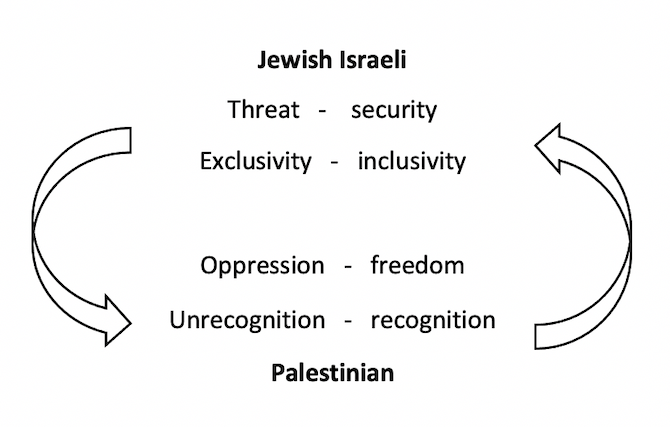

My own work has shown how the dialogical nature of the conflict might be usefully used as a base from which to attempt to understand the social reality of those enmeshed within this tragic quagmire. In so doing it can stand as a foundation from which to understand the suffering, the ensuing hate, the all too familiar pattern of fighting to the death to produce what might be deemed a heroic winner or to score a political victory. This trajectory starts not by researching each group in turn, but by exploring them as one object, as dual processes that continually interact with the other. The model outlined here encapsulates this through the representations revealed during extensive conversations with Jewish and Arab Israelis and Palestinians in their homeland and the diaspora. The ensuing analysis reflects not only their deeply held thematic positions, but the interplay across them to reveal points of intergroup tensions, rather than solely assuming binaries are set in stone. Each dyadic pair embodies the interdependence across opposing positions, both as a point for discussion and as a continuum where positions may be plotted across the dyad as shown below:

Threat – Security / Oppression – Freedom

Threat and security remain paramount for the Jewish Israelis born from a collective past of tragedy and loss, including the horrors of the Holocaust. As fear has remained paramount in the collective consciousness, only security of the highest order is felt to possibly act as a balancer to assuage their subjective vulnerable position and sense of victimhood. However, this has come at a cost to the sovereignty and personal freedom of the Palestinian people through oppressive practices at the hand of Israeli state domination. The experience of existing in the occupied territories in the West Bank and East Jerusalem and the suffocating blockade in Gaza has negatively touched every aspect of life to an unacceptable and inhumane degree. Time has only served to act as a harbinger of any possible end to this reality. Hopes have risen as structural changes, like the Oslo Accords in the early 1990s that beckoned a shift, only to fall back into the pit of oppression, as the once promised ‘two state solution’ or any other solution to end the occupation, remains an unfulfilled dream. Jewish settlements have continually expanded on land within the borders of what the map for any proposed nation was envisaged. Within this quadrangle there are possible discussions around the meaning and delivery of justice – injustice as a possible way forward to explore these contexts at both macro and micro levels.

Exclusivity – Inclusivity / Unrecognition – Recognition

Discussions around Israel as a homogenous Jewish state is frequently an issue that individuals from both groups want to air, particularly for the minority 20% of Israeli citizens, descendants of the Palestinians who remained in Israel following the birth of the state in 1948. Each group live within their different communities, tell different stories of their quasi-segregated lifestyles under different cultural and to some extent state systems, leading to the solidifying of group boundaries that sit astride the magnitude of collective identities. Cross-group contact projects, pursued to share understanding and improved relationships, have found that each group differ in their responses to the other. A consistent finding is the lack of recognition of the minorities past and present political experiences as the Jewish-Israeli narrative overrides points of possibilities of dialogue. Discussing this through the lens of equality-inequality airs the grievances of both groups, both in terms of national belonging/status and planning for a future where boundaries are given the chance of softening.

All examples of boundary softening resulting in an intergroup space for developing communal and consensual relationships, that have developed and flourished during these years, can be conceptually traced across the interdependence of all the dyads described. Think of joint Israeli and Palestinian organisations that share the actual lived reality to propose radical change to seek to end the occupation, human rights groups and within Israel, educational and equal employment opportunities. They may be small in number, but big in future aspirations, believing that genuine dialogue can begin to shift the personal, then the structural machinery that underlies the present reality. Is now the time for sustained national and global reflection?

1 Comments