by Maarya Rabbani

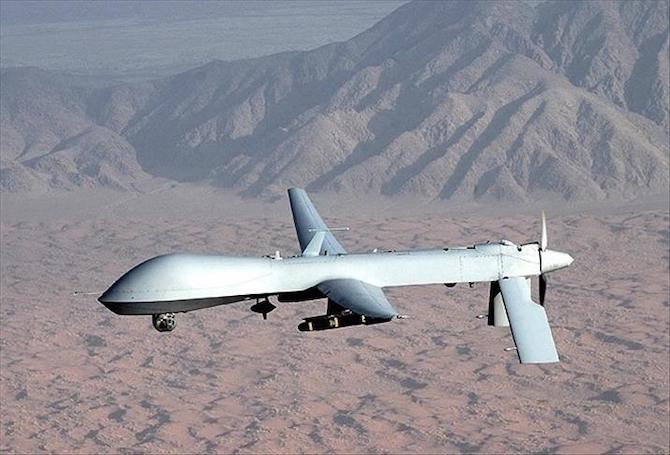

On 29 August 2021, just two weeks after the US military withdrawal from Afghanistan, a drone strike mistakenly targeted and killed Zemari Ahmadi in his car as he was pulling up to the driveway of his home in Kabul. While the strike was intended for an ISIS-K terrorist, it instead killed Zemari and nine of his family members, seven of whom were children. The airstrike was supposedly a retaliation for a suicide bombing near the airport days earlier, which claimed the lives of around 200 people, including 13 US service members. An investigation, spearheaded by The New York Times, coaxed the Biden administration to eventually admit that it indeed was a ‘tragic mistake,’ although this mistake was one far too commonly experienced by Afghans, Yemenis, Somalis, Syrians and Iraqis.

As a matter of fact, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism claims that there have been at least 13,072 confirmed drone strikes on Afghanistan since 2015 – an egregious number of strikes considering the US found Osama Bin Laden in 2011, sheltered in a residential compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan – which was the pretext for the usage of drone strikes in the first place.

Despite the nascent and thorny ethical concerns of drone warfare, news articles and headlines rarely convey the magnitude of lethal drone strikes perpetrated by the US military in the Middle East. Behind the specialised language of techno-strategists and defence analysts, one is faced with a bizarre obfuscation of civilian death. Buoyed by mainstream media, an alarming preponderance of metaphors and passive-voice reporting have denied any chance to hold drone atrocity perpetrators to account. The role of such specialised language both reflects and shapes the nature of American foreign policy – a disproportionate monopoly of power that allows defence strategists to act as they do, without facing legal or ethical repercussions.

By underscoring the framing of such language, one highlights the necropolitical hegemony the US military wields. By necropolitical hegemony I am referring to Achille Mbembe’s theoretical framework which exemplifies the relationship between the sovereign decision to kill, and inevitably have control over who shall and shall not live.

In Frames of War, Judith Butler (2009: 1) similarly analyses the ‘modes of regulating affective and ethical dispositions through a selective and differential framing of violence.’ By following this lead, one is confronted by the construction and justification of the value of lives and deaths as framed by the media for the consumption of Islamophobic and racial linguistic profiling of brown people from the Global South.

Thus, the framing process of the killing of families and destruction of villages under phrases like ‘collateral damage’ and ‘botched attacks’ is inextricably tied to the dissemination of war propaganda, in the age of drone warfare and participatory media. Words like these are pernicious in their ubiquitous usage online, which does little to consider responsibility and accountability for violence in war, as Western military interventionism leaves behind a legacy of impunity for harm to civilians. As a matter of fact, this existing culture of impunity has been institutionalised under a broader banner of good governance and human rights, as these are prototypical democratic governments at the helm of such unethical militaristic ventures.

Meaning-making in this context, is accomplished through definitions and categorisations in language, and it is therefore an imperative that we problematise its role in the illegitimately justified killings of victims, especially as it is perpetuated in discourse. Different framings of discourse surrounding death and dying intersect with the way certain attributes are associated with the perpetrator and how this is similarly produced and consumed in the media.

It is in the same vein that the trauma narrative is always centred around soldiers and not the people that they terrorised in the Global South. Why is it that we focus upon PTSD suffered by ‘the troops’ but the systematically enacted violence perpetrated by Western military forces in the Middle East is merely the figment of a paranoid or politically motivated imagination.

The discourse of cost, in the utilitarian lens of the positive judgement for killing by drone strikes is exactly the justification needed to construe the act of the killing as legitimate; and its victims as either guilty or not worthy of life. This is what Judith Butler (2015) denotes as individuals with non-grievable lives.

In this process, death is denigrated to a trivial construction of a desire to perpetuate a siege mentality of its victims and serves to put an end to legitimate criticism of the abuse of drone strikes in the first place.

The spectatorial gaze we exhibit as the intended audience for such atrocities fictionalise and minimise the lives of the victims as not only non-grievable, but also enjoyable and worthy of such death.

To this end, I wonder why anyone would prioritise agents of the imperial core over the people that they terrorised and to what extent the media excuses neocolonialism, instead of ending it.

The 13,072 confirmed strikes figure is between Jan 2004 – Feb 2020, not since 2015 as the graph would indicate on the provided TBIJ source. Another TBJI page indicates these dates clearer. https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/projects/drone-war/afghanistan

An amoral, out of control war machine blessed by a leader once regarded as America’s great hope, Barak Obama,.

Bipartisan support for terror – that’s what the senseless obliteration of Zemari Ahmadi and his family signifies.