by Iván Cano-Gomez, Cece Kim, P.J. Henry & Jennifer Sheehy-Skeffington

By the end of the twentieth century, the Western ideal — focused on free thought and governance of the people by the people — had seemingly triumphed. Western liberal democratic values could be found across the world, evidenced by societies defined by capitalist principles and democratic beliefs. Yet into the twenty-first century, the recognition that market forces were resulting in unfair and unsustainable ways of life cropped up in various forms. Economic and cultural factors prompted those who had been raised with a sense of fair competition and social advancement via hard work and discipline to feel alienated as their efforts of improving their societal status fell short. Currently, ethnic nationalism and authoritarian populism are gaining prominence across the world, precipitating a decline in confidence in the post-1945 liberal democratic order established by global elites.

What will be the new order’s foundations? To address this question, we look toward what is arguably the strongest weapon held by advocates of liberal democratic values: the liberalising nature of education in diverse university settings. In particular, recent years have seen the growth of ‘global universities’, which export the Western model of liberal arts education to locations in Asia and the Middle East. These give the opportunity for academically accomplished young people from both Western and non-Western countries to come together in a diverse university setting with a liberal arts ethos, during a critical period of the development of social and political attitudes. Through the use of longitudinal surveys, our research project brings a political psychology lens to examine the emergence of identities, outlooks and social attitudes in an elite global university setting.

This is not just any global university setting, however; it is one based in a country that is governed by a ruling family not associated with liberal democratic values: the United Arab Emirates (UAE). We focus on New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD), an institution established with the goal of advancing liberal arts education in the Middle East, a setting where such education has been traditionally underdeveloped. Fuelled by liberal values and home to a high-achieving student body representing more than 120 countries and various ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds, NYUAD arguably represents globalisation in its most empowering, enlightening form.

Launched in the beginning of the 2021-22 academic year, our first survey had a response rate of more than 70% of the incoming class (388 out of 541), whom we plan to follow up yearly until graduation. In this article, we focus on students for whom this liberalising task may face the greatest challenge: those who report coming from non-democratic Middle Eastern countries. We summarise preliminary analyses of predictors of support for democratic versus authoritarian forms of governance to shed light on the psychological underpinnings of democratic hesitancy at the start of a Western liberal education. Note, these data are preliminary as they come from a small sample from only the first wave of what will be a multi-wave survey.

Democratic Support Depends on Effective and Fair Governance and Religiosity

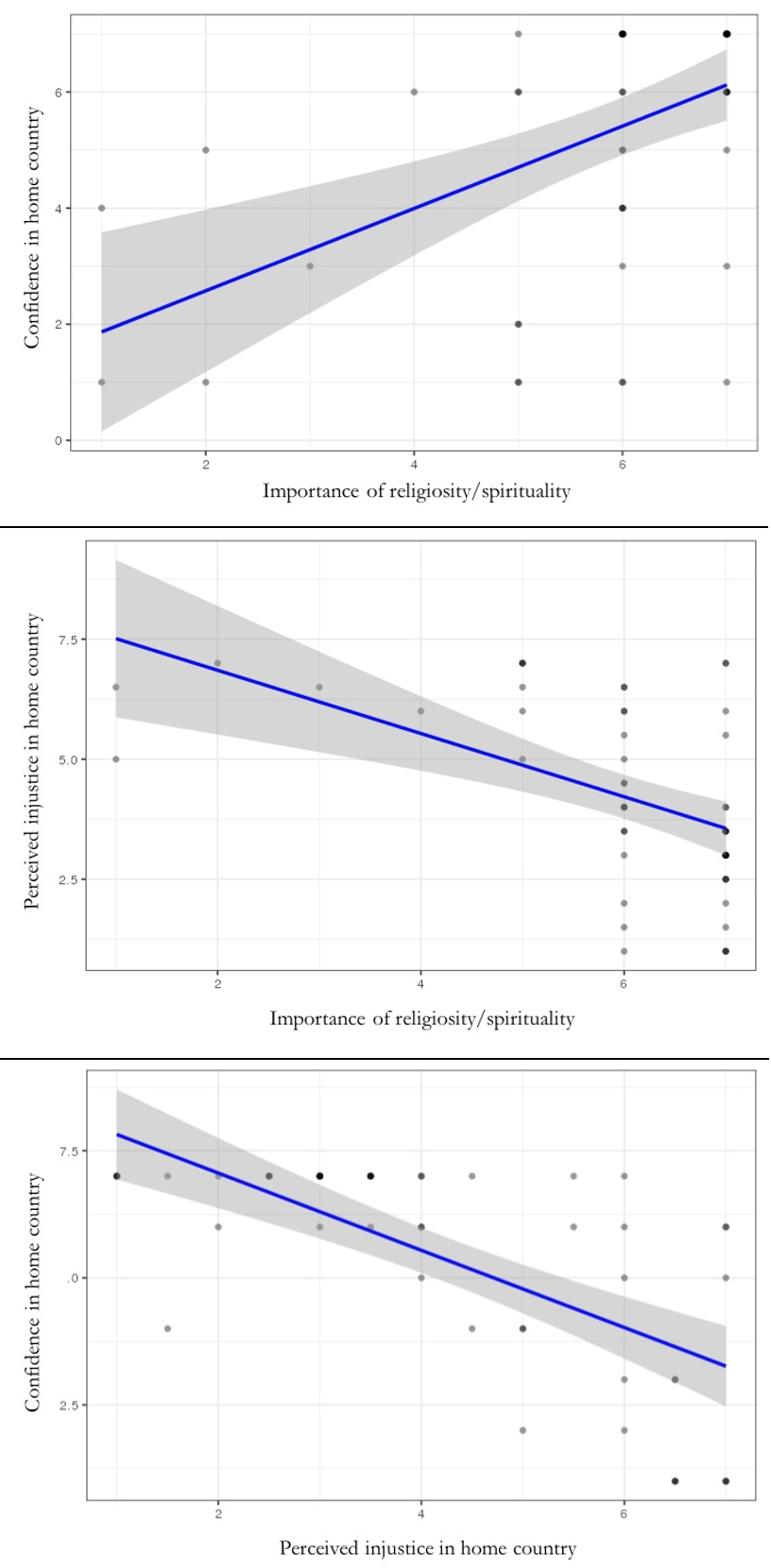

A first examination of the data reveals that among respondents from non-democratic Middle Eastern countries, religion/spirituality is associated with both confidence in one’s country’s governance, and perceived home country injustice (which themselves are inversely related – see Figure 1).

This finding suggests that among Middle Eastern students from nondemocracies in an elite, global university setting, the more important religion is in one’s life, the more confidence one has in how one’s country is governed, and the less injustice one perceives. Several interpretations are possible: perhaps religious convictions are used to evaluate or legitimise government behaviour, or perhaps students are thinking about how governments incorporate religion into policy (e.g., appropriate norms of behaviour). Whatever the reason, it appears that in these young Middle Eastern leaders’ minds, there is a connection between personal religious conviction and attitudes toward how their non-democratic states are doing.

To see whether the above perceptions relate to the core question of democratic values, we asked these same students about the importance they placed on various models of leadership for the successful running of a country, from democratic voting to the power of one person at the top.

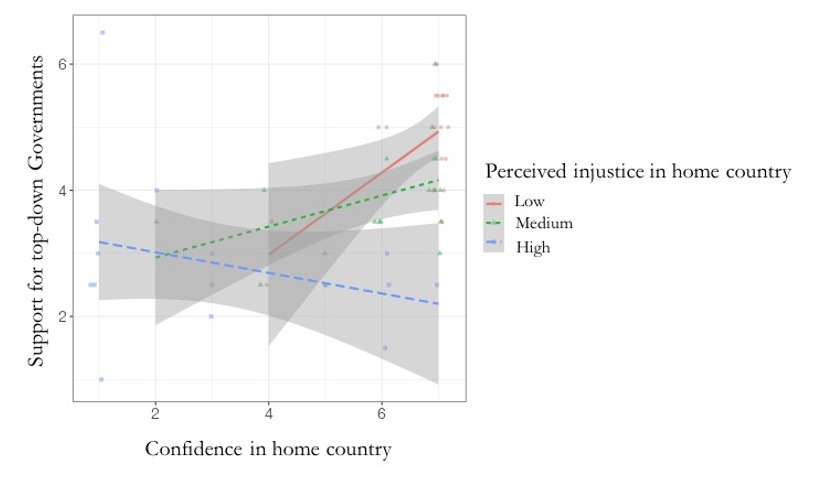

Among this subsample, those who are confident that their country functions well are more supportive of non-democratic governments, but only insofar as they also see their country as just (Figure 2).

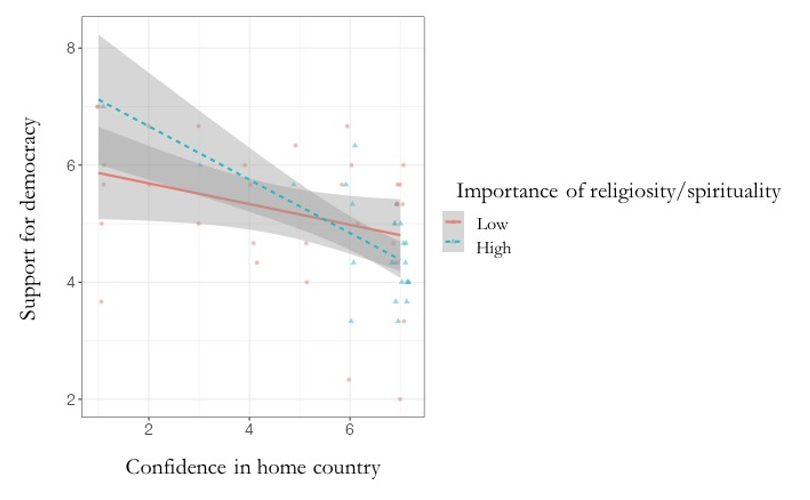

Openness to nondemocratic regimes, however, does not necessarily imply the absence of pro-democracy attitudes. Indeed, the relationship between confidence in governance and support for democratic regimes depends on the importance of religion: living in a well-functioning non-democratic system in the Middle East is associated with lower support for democratic governments for those for whom religion is personally important (Figure 3). Taking all of these findings together, it seems that a combination of notions of justice, effective governance, and religiosity seem to create the conditions necessary for the next generation of leaders to oppose non-democratic regimes.

Conclusion: Governance Trumps Democracy

Our data supports the idea that the apparent triumph of liberal democratic ideals with which the last century ended was more precarious than it seemed. Rather than an inevitable global spread of support for democracy for democracy’s sake, pro-democratic sentiment may have relied on the association between democracy on the one hand, and justice, effective governance, and desirable secularism on the other. Once we move from secularised Western settings to a context with high levels of religiosity, pro-democratic sentiment is not so invincible. Rather, in the eyes of our high-achieving students from Middle Eastern quasi-autocracies, as long as a country is seen as effectively governed with no visible injustices, there is no need for it to be democratic. Indeed, the mostly wealthy non-democratic states in the Middle East seem to be offering an example of desirable population goals being achieved without any intimations toward democracy at all.

Again, these results are based on only a relatively small sample. As we analyse data from new cohorts and future waves, we will see if these findings hold, in addition to investigating if exposure to education from an American liberal arts institution, alongside students from all over the world, will disrupt this pattern. Conversely, we will be able to see whether students from democratic settings all over the world, who will be gaining exposure to a well-functioning non-democracy throughout their time at NYUAD, may see their own assumptions about democracy as a principled ideal versus as an instrumental mechanism being challenged.

This blog post is part of the Academic Collaboration project Global Identity an Uncertain World: A Study of Social Attitudes at an International UAE University, in collaboration with the United Arab Emirates University and NYU Abu Dhabi. Iván Cano-Gomez and Cece Kim are research assistants on the project, while P.J. Henry and Jennifer Sheehy-Skeffington are co-Principal Investigators.