by Sana Tannoury-Karam

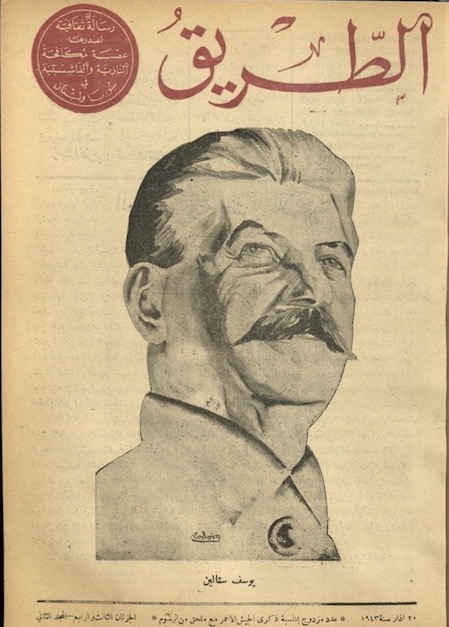

Omar Fakhoury (1895-1946), a Lebanese intellectual and literary critic, published an article in al-Tariq in 1943 arguing for the Soviet Union as “the cornerstone for building a new world…for building a new humanity.” That entire March issue of al-Tariq, a journal established as the mouthpiece of the League Against Nazism and Fascism in Syria and Lebanon in 1941, was dedicated to the anniversary of the Red Army. Boasting a portrait of Joseph Stalin at the front page, the issue featured a range of articles from leftist intellectuals within the League and the circles of the Communist Party of Syria and Lebanon praising the prowess of the Red Army and enumerating Soviet society’s advancements in medicine, social and economic development, literature, and military power.

For a generation of Arab leftist intellectuals active during the interwar years and particularly during World War Two, the Soviet Union represented a ‘miraculous’ case of modernisation, a success story of a country that managed to rapidly modernise and even exceed the levels of progress and sophistication of western nations. Its trajectory since 1917 represented a model for progress achieved through socialism and internationalism. In an almost overwhelming majority of articles that filled the pages of al-Tariq and League speeches, contributors agreed that the Soviet Union constituted the one example in the world of a group of people who had been suffering from ‘backwardness’ but have managed to progress and even surpass the ‘West’ in a short matter of time. The highest point of fascination with the Soviet Union was its military might, manifested clearly in its successes in the face of the German war machine. Standing first against colonialism, and then steadily against fascism and Nazism, the Soviet Union became a model of progress achieved through socialism, and this in turn worked to increase its appeal for intellectuals, activists, and the general public as well.

This generation of Arab leftist intellectuals adhered to a very positivistic framework that assumed the linearity of time and supported the idea of ‘progress’; they also saw the world functioning on parallel and often overlapping timelines, with some stuck in the past while others resided in the future. The socialist project, in its Bolshevik iteration and as presented by the Soviet Union during the pre-cold war period, was seen as an equaliser, as a chance to create a universal timeline through internationalism upon which the world moved forward together.

The Soviet Union as ‘future’ was not only a temporal construct as much as it was also a spatial framework through which Arab intellectuals shifted modernisation discourses of the Nahda from a west-east plane to east-east imaginaries. For those who saw western colonialism as problematic, oppressive, the western ‘model’ of modernisation and progress could not be the one emulated. The Soviet Union projected itself as an ‘eastern’ power as much as leftists in the colonised ‘East’ saw it as such. Within an anti-colonial discourse, the Soviet Union built an entire infrastructure for the ‘oppressed peoples of the East’ to assist and guide them in their march towards socialism and progress.

This illusion of the Soviet Union as future, however, started to disintegrate by the end of World War Two, with Stalin’s crimes becoming more globally known, the increased Soviet pressure to purge and purify communist parties across the world, and more specifically for Arab leftists, with the Soviet Union’s acceptance of the partition of Palestine. Some leftists began questioning the imperialist nature of the Soviet Union, thus creating the first schisms within the Arab left as early as the 1940s, while others who chose to continue to adhere to the Stalinist Soviet line throughout the twentieth century.

Today, the Russian state builds on the legacies of the Soviet Union seeking to present itself as a ‘future’ as well. Vladimir Putin specifically references Stalinist ideals and policies to explain his expansionist and imperial ambitions in Europe as well as in the Middle East. This reflection on an earlier generation of Arab leftists who sought the Soviet Union as a future allows us to reflect on the following questions: How can today’s Arab left, which chooses to distance itself from the Russian Putin, reconcile itself with this past? Is the Arab left capable of rethinking its imagination of the future as disentangled from imperialism and authoritarianism? How does the future look like for those who believe the legacy of the Arab and internationalist left of the 20th century lies in Putin’s vision of the world?

This piece is part of a series on the idea of the future as it relates to Arab media and cultures, based on contributions from panellists in an LSE research symposium in May 2022. Read the introduction here, and see other pieces below. For more on the LSE Academic Collaboration project with the American University of Sharjah, ‘Arab News Futures’, see here.

In this series:

- ‘The Future in Arab Media and Cultures‘ by Omar Al-Ghazzi & Abeer Al-Najjar

- ‘The Soviet Union as ‘Future’: the Socialist Imaginary of Arab Intellectuals during the Mandate Period‘ by Sana Tannoury-Karam

- ‘Visiting Lebanon’s Future in its Past‘ by Ghenwa Hayek

- ‘Historians and the Future: Abdallah Laroui’s Prescriptions for a Recovered Moroccan Modernity‘ by Idriss Jebari