by Erik Asplund & Sharon Pia Hickey

As Turkey grapples with the aftermath of two devastating earthquakes, questions have arisen about whether the 2023 general and presidential elections will be postponed or held under a state of emergency. According to International IDEA’s Democracy Tracker, Turkey’s democratic performance has been consistently declining over the past two decades. This worrying trend has led to speculation that the 2023 elections could be a pivotal moment, and perhaps last chance, to forestall further democratic decline.

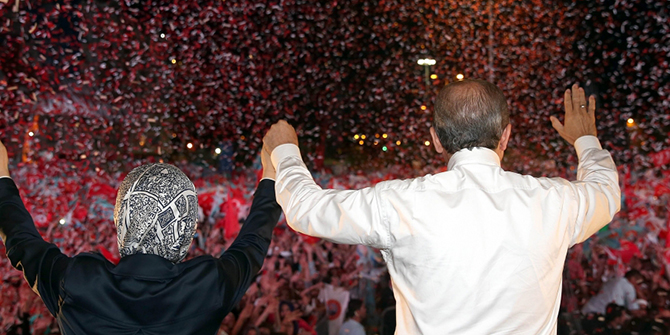

Several weeks before the earthquakes struck, President Erdoğan announced that elections would be moved to 14 May, approximately a month earlier than scheduled. Having held office for two decades, first as prime minister in 2003 and then as president since 2014, Erdoğan claimed that his upcoming candidacy would not fall afoul of the two-term presidential term limit since his first term was before Turkey transitioned from a parliamentary system to a (super-) presidential system of government. His party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), has been in power since 2002, overseeing an authoritarian shift characterised by concentration of power in the executive, arrests of political opposition and weakening of democratic institutions. Despite these developments, elections in Turkey are still considered competitive, and Erdoğan was due to face his toughest electoral challenge yet as the country continues to suffer from a spiralling economic crisis.

Since the earthquake, Erdoğan has not announced any amendment to the previously scheduled 14 May election date, which would need to be officially announced 60 days in advance. However, a senior member of the ruling AKP, Bülent Arınç, has recommended postponement of the election and suggested it either be held in November 2023, together with local elections in March 2024, or on a new date agreed together with all other parties as per a Twitter post.

Turkey’s constitution does not foresee postponement of elections except in case of war. Therefore, if Erdoğan decided to change the date again, it could be no later than June. A postponement beyond June would not only violate the constitution but undermine the legitimacy of the elections, potentially triggering a constitutional crisis. Such a postponement would require a constitutional amendment passed by a two-thirds majority in parliament – impossible without opposition backing. Representatives of the Turkish opposition Iyi Party, Meral Akşener, have stated that the election should be pushed back to its original date, namely 18 June 2023, because of the earthquake. While postponing the election could potentially benefit the opposition, who before the earthquake were struggling to name a candidate to oppose Erdoğan, it is unclear whether they would agree to such a move because of the precedent it could set. The elections could still take place in May or June but perhaps under a state of emergency. The current three-month state of emergency, declared on 7 February in the ten provinces most affected by the earthquake, is due to end shortly before 14 May, but this could be extended.

Turkey has previously held elections under a state of emergency, which is in general an uncommon practice. The June 2018 general elections in Turkey were held under a state of emergency that lasted for two years and was imposed after a failed military coup. Whereas the decision to uphold a state of emergency during the 2018 election was criticised by international organisations and opposition parties, the current, catastrophic context is very different. As of 17 February, the earthquakes have killed more than 43,000 people, and tens of thousands of people from ten regions of Turkey have been injured, made homeless or internally displaced. Given the huge numbers of deaths, injuries, displaced people (which may include election officials) as well as destruction to critical infrastructure (which may include schools which typically are used for polling stations), the challenge of holding elections in the most affected areas will be immense.

A state of emergency may be a prerequisite to holding elections in the most affected regions to make certain that resources and funds are used for relief and reconstruction efforts. Political campaigns are democratic activities that provide citizens with the information they need to make informed decisions when they arrive at the ballot box. Therefore, any extension of the current state of emergency should focus on disaster and humanitarian relief rather than restricting opportunities for political parties to campaign. As the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association confirmed in 2021, ‘declaration of states of emergency must be strictly limited; also the state must ensure the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly is respected throughout the electoral process; any limitations must comply with the requirements of legality, legitimate objectives necessity, and proportionality, in accordance with international human rights law.’

Postponing elections during a natural disaster is not extraordinary. In fact, during the Covid-19 pandemic, more than 80 countries and territories across the globe opted to postpone national and subnational elections, with 42 countries and territories postponing national elections and referendums. Postponing an election is not always an undemocratic option, as the integrity of the electoral process is likely to be undermined in such a scenario and humanitarian considerations may justify short-term postponements.

In several countries such as Haiti, Jamaica, Japan, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, and the USA, national and subnational elections were postponed due to natural hazards such as hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, floods, and earthquakes. For example, the 2010 legislative elections in Haiti were postponed for 10 months in the aftermath of a magnitude 7 earthquake that claimed the lives of 220,000 people. Voter registration, political campaigning, and the election itself were further complicated by a hurricane and cholera outbreak. Similarly, the magnitude 9 earthquake that struck the coast of Honshu, Japan in March 2011 triggered a tsunami and nuclear disaster at the Fukushima plant leading to the deaths of 18,500 people and the postponement of the April 2011 unified local elections in certain municipalities. Also, the 2020 Indonesia elections, which were initially planned for September 2020 but were held in December 2020, were organised during the Covid-19 pandemic and under extreme weather conditions in parts of the country.

Nevertheless, any decision to postpone elections or to hold elections under an emergency needs caution and careful consideration. National authorities responsible for determining the necessity of postponing elections should, when declaring the postponement, define a clear roadmap that details actions and milestones that mitigate any possible undemocratic implications resulting from their decisions. The measures should be proportionate, temporary, and non-discriminatory, respecting conditions for derogation of the fundamental right to vote under the state’s constitution and international human rights law. Any decision to delay elections should be informed by consultations with political parties, election management bodies, and experts to ensure respect for human rights.

Moreover, any decision to hold elections in the aftermath of a natural disaster must consider a range of questions on the administration of elections. For Turkey, it is important to take into account findings and lessons learned on the importance of risk and crisis management, inter-agency collaboration (especially with civil contingency and disaster relief agencies and health agencies), and strategic communication from other countries that have held elections in the aftermath of natural disasters. This may prove crucial in maintaining electoral integrity.

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]