by Taif Alkhudary

In Zubair, a city south of Basra, a group of women led by an Afro-Iraqi activist worked with a local NGO on a campaign to tackle the piles of rubbish that littered the area’s streets. At first, they approached the municipality asking them to provide them with proper waste disposal facilities. However, the municipality advised that this was the responsibility of the Basra Oil Company (BOC), who in turn informed the women that they could not afford to support their project. In the end, despite making billions in oil revenues monthly, BOC agreed only to provide the citizens of the city of Zubair, where Iraqis of African descent are concentrated, with old oil barrels to use as makeshift bins.

It might be argued that the neglect described in this story is no different to that which might be told about a number of other cities across Iraq, as a result of systemic political corruption and lack of government accountability. However, the effects of these issues are compounded for Iraqis of African descent, who have suffered for centuries from structural forms of racism and discrimination often tied to Basra’s position as a commercial hub.

Overt vs Structural Racism

Current research on Afro-Iraqis is extremely scarce in both English and Arabic. When it has been undertaken, researchers have argued that racism against Iraqis of African descent manifests itself through the casual everyday use of slurs such as the term abed (meaning ‘slave’), as well as deeply held racist stereotypes which portray Iraqis of African descent as simple-minded, entertainers, angry and unclean. What is more, such attitudes have limited the kinds of positions that Afro-Iraqis can occupy in society, preventing them from entering politics and leading to the assassination of the community’s most prominent political activist in 2013.

For the most part, existing research on Iraqis of African descent, such as that outlined above, has focused on individual or overt forms of racism. It has not examined how structural racism functions on a larger scale with the adverse conditions produced for racial minorities continuing to exist apart from the actions or beliefs of individuals. In Basra, Iraq’s only port city and centre of commerce throughout history, I am particularly interested in how structural racism might be thought about from a political economic and ecological perspective.

Pollution Sinks

The city of Zubair, where our protagonists carried out their anti-waste campaign, is one of the most polluted cities in Iraq. In addition to the masses of waste strewn across its streets, it is the site of several petrochemical and fertiliser plants and sits on the edge of the oldest oil field to be ‘discovered’ in southern Iraq. Smoke plumes released from the factories’ chimneys and from the gas flared at the oil field extend into the sky for miles and can be seen across Basra. According to a recent study by the International Republican Institute (IRI), Zubair also ranks in the lowest per capita income quintile and suffers from particularly poor service provision, making it a hotbed for both protests demanding services and broader anti-government demonstrations.

Basra has recently began to garner attention due to the high levels of pollution there, which impacts the health and quality of life of all its citizens and environment. However, it is perhaps not unconnected that one of the most polluted areas in the province also happens to be home to Iraqis of African descent. Research on racial capitalism has shown that polluting industries are disproportionately found in areas populated by racialised communities. In these areas, ‘pollution sinks’ are not just the land, air and water, as my interlocuters have often told me, but rather as Laura Paulido has argued, devalued bodies such as those of the Afro-Iraqi community also operate as ‘sinks’ carrying out the labour of absorbing toxic externalities that form the basis of Iraq’s economy. Thus, while all Basrawis may suffer from pollution, capitalist accumulation – built on the unequal differentiation of human value – means that they do not do so to the same extent.

Histories of Slavery and Revolt

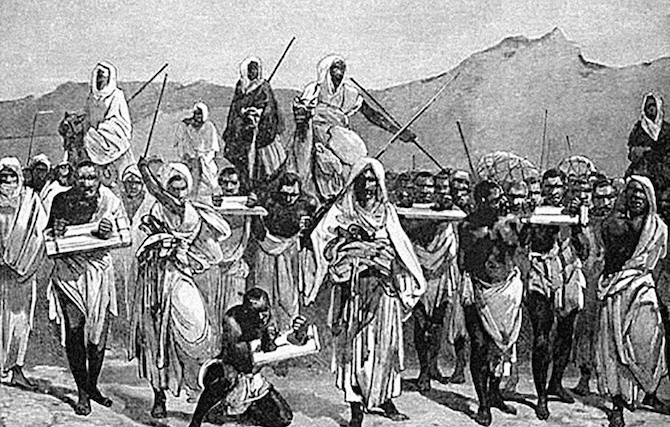

However, racialisation and disposability of the bodies of Afro-Iraqis also has a much longer history that precedes capitalist forms of trade. This dates back to the Abbasid empire, when Basra was a major slave port. During this period, slaves were often forcibly transported to modern-day Iraq from countries including modern-day Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Zanzibar and Ethiopia. They were forced to undertake back breaking labour, including draining salt marshes, cultivating sugarcane and extracting molasses from dates. They were also sacrificed in domestic battles between aristocrats and royalty. In response to this racialisation, justified through recourse to Islamic theology, which posited Africans as pagans and nonbelievers, confining them to permanent servitude to lighter-skinned Arabs, enslaved Africans in modern-day Basra also led one of the first and the longest lasting slave revolts in history, known as the Zanj rebellion.

Future Directions for Research

The individual forms of racism and discrimination faced by Afro-Iraqis are well established in existing – albeit extremely scarce – research on the topic. However, what remains unexamined is how structural racism, including in political economic systems, works to determine the life chances of Iraqis of African descent today. What is more, while the presence of Afro-Iraqis in Basra is a reminder of the central role that the city played in the Indian Ocean slave trade, less attention has been paid to how the collective memory of disposability, forced labour and revolt has been transmitted between generations and contributed to the formation of community identity among Afro-Iraqis in Southern Iraq.

Through ethnographic research carried out in Basra, this project commissioned as part of the FCDO-funded PeaceRep Programme, will seek to answer these questions, among others. In so doing, it will also present broader insights into what examining Basra from the perspective of the Afro-Iraqi community, might reveal about the unique socio-economic and political context of Iraq’s only port city.