by Taif Alkhudary

On a crisp winter day in Baghdad, I took a taxi to the political office of the Taqadom MP Wihda Al-Jumaili. The veteran politician has a street named after her in Dora, Southern Baghdad, where she meets with hundreds of constituents every day. Al-Jumaili’s celebrity is perhaps just one indication of how far women MPs have come in Iraq.

In fact, in the 2021 elections women MPs won 95 seats in parliament – the highest number to be achieved in Iraq to date and 14% more than their quota allocation. However, despite these gains and a guarantee of 25% of all parliamentary seats in the constitution, my interviews with women MPs, electoral candidates and civil society activists, indicate that women continue to lack substantive representation in Iraq.

Women’s Absence from Political Parties

The women’s quota was introduced in 2005 as a way of ensuring that women are represented in the Iraqi parliament. Since then, as one interlocuter put it, the quota has served political parties that do not have women among their ranks, more than it has served women themselves.

Perhaps with the exception of some of the Kurdish parties, women have continued to be more or less absent from political parties in Iraq. This is even true for the post-2019 parties, who despite the large participation of women in the Tishreen protests also suffer from lack of women in their ranks. Instead, during elections political parties choose women from their familial or social networks who have large followings in their district or province to run as candidates, allowing their parties to gain guaranteed seats with fewer votes through the Gender Quota. These women often lack any political experience and are thrown into parliament without any prior training, a process that civil society activists refer to as being taken ‘from the house to the fire’ (من الدار إلى النار). Their inexperience and social and familial ties to established male politicians, means that these women MPs are more likely to toe the party line. Thus, despite their presence in parliament, they are less likely to advocate for women’s rights issues without the support of their party.

What is more, cognisant to the importance of the Women, Children and Family Committee in pushing for and supporting gender-sensitive legislation, Iraq’s heteropatriarchal political parties have ensured that it is either always headed or staffed by conservative women MPs. Between 2010-2018, the Committee was headed by Intisar Al-Jabour, at the time a member of Ayad Allawi’s National Coalition, and who was a stringent supporter of the anti-domestic violence law. Since then, however, the committee has been headed by either Sadrist or State of Law MPs, a move that activists I spoke to attributed to an attempt on the part of Islamist parties to limit the effectiveness of the committee as a body tasked with pushing for women’s rights by deliberately putting conservative women MPs in top positions. What is more, women MPs themselves are often disinterested in joining the Women, Children and Family Committee, and would rather join committees where they are more likely to be able to embezzle state funds and ‘do business deals.’ As such, in both the 2018 and 2021 parliamentary terms the committee had an insufficient number of members, leading the Speaker to bring in a new rule making all women MPs automatically part of the Women, Children and Family Committee and allowing them to choose an additional committee to join (Interviews with three women MPs, February 2024).

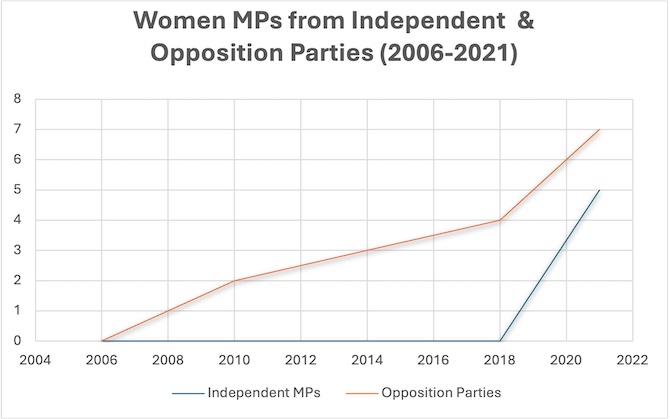

Preliminary analyses of open-source elections data suggests that for the first time the 2021 elections saw the entry of five independent women MPs into parliament where previously there had been none (Table 1). It also indicates that the number of women MPs from outside the traditional dominant post-2003 parties, or what might be called opposition parties, has steadily increased. This suggests that a new generation of women MPs are entering politics that do not necessarily owe their positions to Iraq’s dominant heteropatriarchal political parties. To some extent, this increase in independent women MPs stems from changes to the electoral law, which in 2021 introduced a first-past-the-post system favouring independent candidates rather than political parties. Ahead of the 2023 provincial elections, the electoral law was changed back to the Sainte-Lägue 1.7 system, which women’s rights advocates have argued is less likely to allow women candidates to win seats outside of the quota.

Furthermore, the ability of independent women MPs to act alone is severely limited because as soon as they enter parliament, they find that they need social and political protection, and as such many of them end up joining political blocs, or even, marrying into political parties. For example, the current head of the Women, Children and Family Committee, Dunia Abdel-Jabbar Al-Shammery, ran as an independent candidate, but has since joined State of Law Coalition. Women MPs with opposition or post-Tishreen parties have also largely left the parties they ran with in the 2021 elections due to accusations of corruption and sectarianism. Therefore, they are unable to use these opposition networks as basis from which to push for pro-women policies in parliament.

Women as Political Leaders

The limited number of women in political parties has also meant that they are largely absent from leadership positions. To some extent, this issue stems from the parties themselves, who continue to exclude women from important positions. For example, out of the 400 members of the general secretariat of the Dawa Party there are only 12 women. In addition, in 2019 when the party held elections for its leadership body – the Shura Council – no women were elected. What is more, women are often excluded from important party meetings which often take place at night, when it is seen to be unacceptable for women to participate.

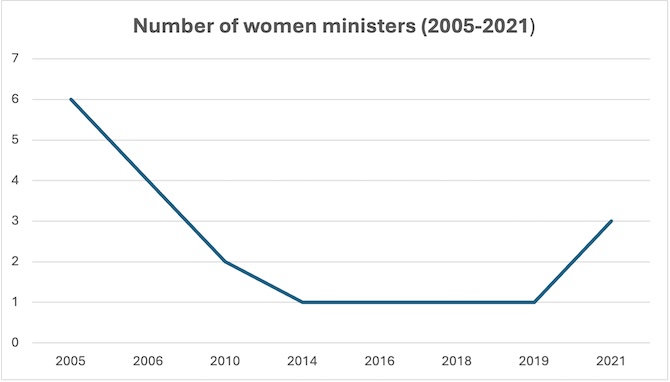

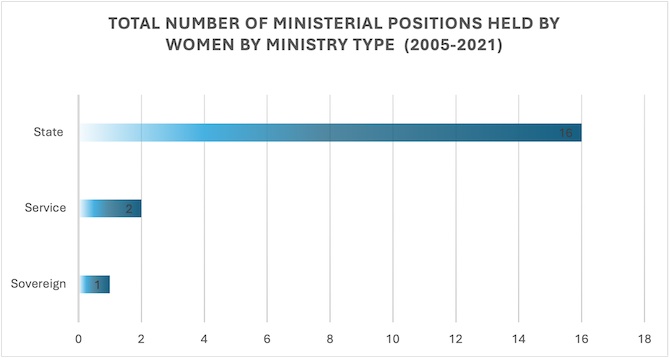

The lack of women in the leadership of the parties themselves coupled with the absence of a “ministerial quota” translates into a lack of women ministers, with the number of women ministers peaking at six following the January 2005 elections (Table 2). The number of women appointed to ministerial positions has seen a downward trend in subsequent elections and cabinet reshuffles. What is more, even when women have held ministerial portfolios these have tended to be in weak and relatively marginalised ministries. These ministries are known among Iraq’s political elite, as ‘state ministries’, and are the least costly according to the points-based system used by Iraqi parties to divide up ministries among themselves following each election. An analysis of ministerial portfolios held by women politicians between 2005 and 2021 demonstrates that the vast majority – 16 out of 19 – held ‘state portfolios’ (Table 3). On only one occasion has a women led a ‘sovereign ministry’ – considered to be the most important and costly of ministries according to the points-based system – in the form of the current Minister of Finance, Taif Sami.

Preliminary Ways Forward

In this article, I have suggested that while the gender quota has worked to ensure that women occupy positions in the Iraqi parliament, they are still absent from leadership roles and the kinds of policies that they can push for remain limited. In order to begin to overcome these challenges, political parties must begin to actively recruit and invest in the development and training of women and ensure that they are reasonably represented in their leadership. To this end, the post-2019 parties may be a good place to start, given that they remain in their political infancy and emerged out of an important moment for Iraqi feminism.

This blog is part of the research project ‘Gendered Networks of Power: The Parliamentary Quota and Women’s Substantive Political Representation in Iraq‘, funded by a grant from the British Institute for the Study of Iraq.

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]