“Instead of endorsing the people’s initiatives, some scholars only bring the same picture as the state-perspective who see the people’s lack of awareness as the leading cause of the increasing numbers of Covid-19 cases in Surabaya”, writes Adrian Perkasa, a PhD candidate at Universitieit Leiden and a lecturer at Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya

_______________________________________________

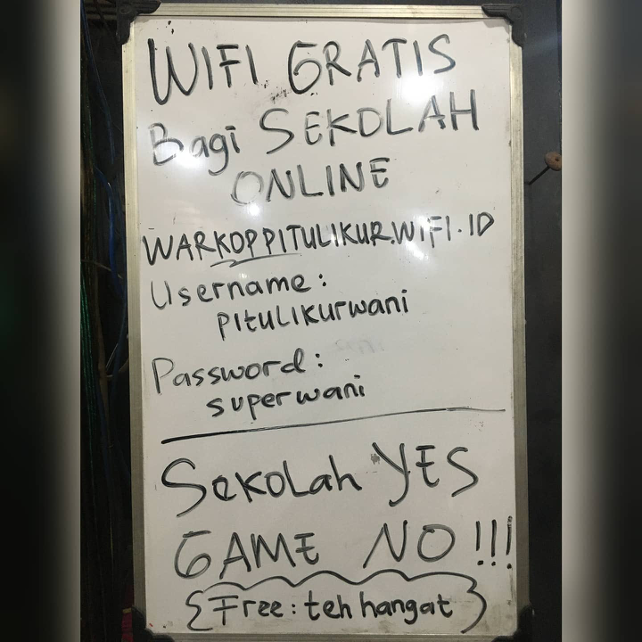

The title of this blog comes from a statement from Husin Ghozali alias Cak Conk, the owner of Warung Kopi (Coffeeshop or warkop) Pitu Likur in Surabaya, Indonesia. His coffee shop went viral in social media in the last week of July 2020 or the beginning of the new school year in Indonesia. The Indonesian government decided to conduct online learning or School from Home (SFH) in all levels of education, from elementary to high school, due to the Covid-19 outbreak. However, many students’ parents were unhappy with this decision, especially in many households in the kampungs of Surabaya. They felt it brings more difficulties to their family, who are already struggling very hard to cope with the new situation. Then, Cak Conk initiated a plan to help many students in his neighbourhood or kampung. He invited students to use the Wi-Fi in his coffeeshop during the SFH (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Not only free access to the internet, but he also provided a glass of tea or milk for the students who spent their school day there.

Figure 1: Free Wi-Fi for Online Schooling, Free: a cup of tea. Warkop Pitu Likur, 2020

Figure 1: Free Wi-Fi for Online Schooling, Free: a cup of tea. Warkop Pitu Likur, 2020

Figure 2: Three high school students are attending online school at Warkop Pitu Likur. Warkop Pitu Likur, 2020

Unfortunately, the municipal government of Surabaya complained about Cak Conk’s initiative. An official from the Dinas Pendidikan (Education Agency) of Surabaya warned students to avoid the public spaces such as warkop to prevent any increasing numbers of Covid-19 cases. In line with this complaint, several members of the Surabaya Parliament also criticised the warkop. They urged the students to stay at home as regulated previously by the government. According to them, Surabaya’s municipality would provide free internet connection in several public spaces in the neighbourhood, such as Balai RW (the neighbourhood hall). However, as of the mid-August 2020, this plan is remaining on paper (Kholisdinuka, 2020). Moreover, the students still come to Warkop Pitu Likur every morning to attend the school online. Cak Conk explained by a phone call with me at the end of July:

Actually, I don’t have any intention to promote my business. I only heard many parents of my son’s friends in the school face difficulties in providing internet for their children. Thus, I just quickly responded by open my Warkop for them.

According to him, the Kampung people are tired of the failure of the government to minimise the pandemic’s effects on their everyday lives (interviewed on 26 July 2020). Surabaya, the second biggest city in Indonesia and the capital of East Java province, has become the epicentre of the Covid-19 outbreak in this province. Moreover, this situation is worsening due to the bitter relationship between the mayor of Surabaya, Tri Rismaharini, and the governor of East Java, Khofifah Indar Parawansa. Many Surabaya people, including Cak Conk, have a particular term referring to this relation as DraSu or Drama Surabaya (Surabaya Drama).

This term is derived from DraKor or Drama Korea (Korean Drama/K-Drama), which has recently become popular in many parts of the world. The first publicly acrimonious dispute between the two figures was over the planning of Surabaya to limit the mobility of people entering the city. The governor refused this plan because, according to her, the large-scale social restriction is by the authority of the regional and national government. A few weeks later, they got involved again in a hostile moment after Tri Rismaharini told the media that the increasing Covid-19 cases in Surabaya were because many new patients in several Surabaya hospitals came from other towns in East Java. Both of them were engaged in conflict over two mobile Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) labs, which had been loaned from the Badan Penanggulangan Bencana Nasional/BNPB (National Mitigation Disaster Agency) (Syambudi, 2020). Early August 2020, the Governor denied the mayor’s claim in the decreasing number of Covid-19 cases in Surabaya.

The political rivalry between these two leaders also affected the pandemic’s management, especially in a hospital and other healthcare facilities. As described by Donny, a doctor in Dr. Soetomo hospital of Surabaya, there are many difficulties emerge for the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic because of that rivalry (interviewed on 26 July 2020). The first and foremost problem, according to him, is there is a lack of coordination between the healthcare facilities under the responsibility of the Surabaya municipality and East Java province. Dr. Soetomo hospital is the Covid-19 referral centre in the Surabaya region operated by East Java province. As early as the Covid-19 outbreak in Surabaya, many new patients sent directly by the healthcare facilities in Surabaya to this hospital bypassed this disease’s national and regional handling procedure. As a result, the hospital becomes an epicentre of the virus contraction. However, the spokesman for the disease task force in Surabaya publicly stated several times that the situation in Surabaya was under control (Widianto and Beo Da Costa, 2020).

The Ikatan Dokter Indonesia/IDI (Indonesian Medical Association) admitted that healthcare workers feel overwhelmed by the high number of patients and increasing workloads due to the governments’ pernicious management. Possibly, the highest rate of healthcare workers’ deaths in the world is in Indonesia (Barker, Walden and Souisa, 2020). Many medics in Surabaya were reportedly infected by the virus, including my father who also works in a hospital. “It’s like a vicious cycle, and the one blames another party and vice versa. The municipal and provincial governments should work together to protect their people. We need gotong royong”, Donny stressed it to me. Again, there is another person who emphasised the importance of gotong royong, loosely translatable into ‘communal or neighbourly help’, to deal with the pandemic.

People practice gotong royong in everyday life and communal activities, from family celebrations such as weddings or engagements to the celebration of religious feasts and national days. It is also not uncommon for kampung people in urban areas like Surabaya to still practice gotong royong. The case of Cak Conk and his warkop is the best example of how gotong royong is relevant during the pandemic. In previous studies, some scholars such as Bowen (1986), Guinness (1986), and Sullivan (1986) argue that gotong royong is a construction from the state, rather than initially embedded in the Indonesian community. Even though this kind of mutual assistance reflects genuine indigenous notions of moral obligations and generalised reciprocity, it is argued that it has been reworked by the state to become a cultural-ideological instrument for the mobilisation of village labour (Bowen, 1986: 545-546). Suwignyo (2019: 407) traced the initial concept of gotong royong to the Dutch colonial period and its further development in the Japanese Occupation era and post-independence Indonesia. According to his research, every government from the 1940s to the 1990s promoted gotong royong extensively as a signifier of collective identity. He concluded that gotong royong became a form of social engineering and ingenious linguistic strategy by which elites orchestrated control over citizenship-making.

Nevertheless, the aspiration of Cak Conk and Doctor Donny in Surabaya seems to contradict such scholarly arguments. Rather than the state or the government that promotes gotong royong, the people are urging their government to act gotong royong when facing troubled times during the pandemic. Or, can it be said that Cak Conk’s initiative for gotong royong is only a particular case or even an exceptional phenomenon?

The recent survey by LaporCovid-19 and the Social Resilience Lab at Nanyang Technological University Singapore has shown that the majority of Surabaya people tend to underestimate the risk of being infected by Covid-19. The economic and social situations also have a significant impact on the lower perception of risk (Persepsi Risiko Surabaya – Lapor Covid19, 2020). Thus, the kampung people who worked as daily labourers or run a small warung like Cak Conk contributed heavily to this number of lower perception. Another scholar in Surabaya, Windhu Purnomo, also stressed the similar argument that most of the Surabaya people only prioritise their economic interests primarily in the traditional market and public spaces (Larasati, 2020). These arguments are in line with the state perspective that often blames people as a main cause of the high number of Covid-19 cases in Surabaya (Meilisa, 2020).

To get a broader picture and understand the situation in Surabaya, I am turning my attention to look at bottom-up responses from other kampungs. Despite many limitations during this time, I tried to conduct fieldwork in online environments. I interviewed several kampung residents in Surabaya whom I had known before. Using WhatsApp video call, I interviewed them including Cak Conk and Doctor Donny. The first kampung where I decided to scrutinise is Kampung Peneleh (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). I have a long and intensive relation with the residence of this kampung for more than a decade. I am currently a local principal investigator of Southeast Asian Neighbourhood Network (SEANNET) in Kampung Peneleh as a case study in Indonesia. I worked with several residents of Kampung Peneleh including Obet, who assisted me in writing field notes from March to August 2020.

Figure 3: An entrance to Kampung Peneleh with notification banners to obey the health protocol. Obet, May 2020

Figure 4: Eid prayer in the Kampung Peneleh during the pandemic. Obet, July 2020.

In the early period of the outbreak, the kampung situation seems to follow the result of the LaporCovid-19 survey. There was a disagreement within the kampung regarding the adaptation of the new health protocol. A group of youth in a neighbourhood association promoted a new hygienic attitude by spraying the disinfectant gas to all the kampung and surrounding areas. However, not everyone, including several elders in the kampung, agreed with their initiative. The situation quickly escalated to physical conflict between a youth neighbourhood association and other groups in the kampung. Eventually, after several heads of Rukun Tetangga/RT (the Neighbourhood Associations) mediated them, the conflict subsided

Perhaps one can quickly assess that the above situation displayed how many groups in the community resisted the new health protocol as also expected from the recent survey. Nevertheless, the root of the dispute within the Kampung Peneleh was not about the resistance of the health protocol after an outbreak. The first and foremost reason why many groups in Kampung Peneleh rejected the plan of fogging or spraying the disinfectant was that this activity was fully sponsored by a political candidate who would be running in a mayoral election at the end of this year. This candidate is promoted by the coalition of political parties who opposed the incumbent mayor from Surabaya. However, the heads of RT in Kampung Peneleh decided only to follow the official protocol from the government.

Indeed, there was another resistance to obey the new health protocol in Kampung Peneleh. Several of kyai (Islamic leaders) and ustadz (Islamic teachers) refused a request from the health protocol to close the mosque until further notice. According to them, it was a heretical view to fear the threat of a virus; all Muslims should only fear God. Moreover, the situation was getting more difficult due to the first request from the government coincided with Ramadan’s coming, a month full of fasting and praying for the Muslim. There is a significant and historical mosque in Peneleh called Masjid Jamik (Grand Mosque). Previously before the Covid-19 outbreak, this place became a centre of religious activities not only for Peneleh people but also from its surrounding neighbourhood during Ramadan. As a consequence, the kyai and ustadz declined the request of the official health protocol. They have been still doing many activities as they usually did in Ramadan before the pandemic.

Later there was a circular letter dated 3 April 2020 from the Nahdlatul Ulama, the biggest Islamic organisation in Indonesia, in response to the Covid-19 outbreak. They issued a decision to slow the spread of Covid-19 by avoiding any activities of meeting and gathering of Muslims in large numbers. It called for the implementation of worship during Ramadan, usually done in the congregation in the mosques or other praying halls, to be held in their respective homes. Other activities relating to the celebration of the Eid al-Fitr feast after Ramadan were also to refer to the provisions and policies of social restrictions and maintain physical distance as determined in the official health protocol by the government (Surat Edaran PB Nahdlatul Ulama, 2020). Likewise, Muhammadiyah, another prominent Islamic organisation in Indonesia, released a similar statement several days earlier (Surat Edaran PP Muhammadiyah, 2020). Although these instructions were not directly implemented in Peneleh, gradually the Kyai and Ustadz followed it. Moreover, these figures also participated in promoting the government’s instruction for the people to stay at home in the Eid al-Fitr feast and not going back to their respective regions or mudik. They did it by gotong royong with other kampung residences, including those who professed other religions such as Christianity, Hinduism, and Confucianism.

Another case came from Kampung Pabean where the biggest traditional market in Surabaya, and even East Java, is located. As expected by the previously mentioned scholar like Windhu Purnomo, indeed, many daily workers in that market are not obeying the health protocol. However, it is only a slice of reality in the market and the kampung, and it is incomplete. Sahib, who is living in this kampung and also a caretaker of the neighbourhood association there, told me another story (interviewed on 27 July 2020). Together with the association, he always reminds everyone in the market and the neighbourhood to follow the health protocol. In addition to that, they provide daily workers in the market with a free mask every day. Furthermore, the neighbourhood association of Kampung Pabean is taking care of the poor people who get infected by the virus and are required to self-quarantine in their house. They voluntarily supply provisions to them during the quarantine: “we should gotong-royong to take care of ourselves.”

To sum up, there are many bottom-up initiatives of the kampung people in Surabaya but still neglected by scholars. Instead of endorsing the people’s initiatives, some scholars only bring the same picture as the state-perspective who see the people’s lack of awareness as the leading cause of the increasing numbers of Covid-19 cases in Surabaya. The people like Cak Conk and the residents of Kampung Peneleh and Kampung Pabean are effectively incorporating the concept of gotong royong as a strategy to face the situation during a pandemic. They urge and challenge the government, especially the Surabaya municipality and East Java provincial government, to put aside the political enmity and do gotong royong to prevent further adverse effects of the Covid-19 outbreak. As Springer (2020: 114) states, in this challenging moment, the people can gather, depending not upon the state and the command of any authority, but on their collectivity. The collectivity, as one could see in gotong royong of the people, is vital not only during this time but also for their future as urban dwellers and Indonesian citizens.

References

Bowen, J. (1986). ‘On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia’. The Journal of Asian Studies, 45(3), pp. 545-561.

Guinness, P. (1986). Harmony and Hierarchy in a Javanese Kampung, Singapore (etc.): Oxford University Press.

Springer, S. (2020). ‘Caring geographies: The COVID-19 interregnum and a return to mutual aid’. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(2), pp.112-115.

Sullivan, J. (1986). ‘Kampung and State: The Role of Government in the Development of Urban Community in Yogyakarta’. Indonesia 041 (April), pp. 63–88.

Suwignyo, A. (2019). Gotong royong as social citizenship in Indonesia, 1940s to 1990s. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 50(3), pp.387-408.

Warkop Pitu Likur. (2020) Hari pertama adek2 kita lagi semangat belajar daring memanfaatkan wifi di warkop PituLikur secara gratis dan free teh hangat juga. Twitter, 20 July. Available at: https://twitter.com/WarkopPituLikur/status/1285192502627074048 [Accessed 26 July 2020]

Warkop Pitu Likur. (2020) Tetap semangat belajar adek2, walaupun dgn keterbatasan dimasa pandemi ini. Twitter, 21 July. Available at: https://twitter.com/WarkopPituLikur/status/1285547938303762432 [Accessed 26 July 2020].

*The author thanks the resident of several kampungs and especially Rohman Obet, as a research assistant in Surabaya. Thanks go to Rita Padawangi and Paul Rabe for the invitation to involve in SEANNET; to Samia Kotele for comments on an early draft; to Hyun Bang Shin and Do Young Oh whose detailed comments and feedbacks improved the main argument of this essay.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.