“The efficacy of contact tracing application or data collection is balanced against concerns for privacy. How much might be too much data collection? And would the ends justify the means?”, writes Farlina Said, an Analyst in Foreign Policy and Security Studies at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia

_______________________________________________

October marked ten months since the first COVID-19 case was detected in Malaysia on January 24, 2020. Slightly lesser than three months after detection, a movement control order (MCO) was announced on March 17 to quell the rise of Malaysian figures that soared to three digits. The movement of people ceased except in supermarkets and places offering essential services. Meanwhile, fibre optic cables and telecommunication towers boomed. Internet traffic in the first week of the MCO increased by 23.5% and a further increase of 8.6% was recorded in the second week. An Opensignal report stated Malaysia’s 4G download speeds dropped from 13.4Mbps on average in early February to an average of 8.8Mbps in the last week of March, signifying the heavy usage and side-effect of people staying at home.

There are two significant trends in Malaysia’s management of the pandemic. The first is the interest in digitalisation which reverberated in the government, business communities and sectors such as healthcare. The second are lessons learned from the usage of technology to mitigate the rapid rate of infection that is a characteristic of the SARS-CoV-2 virus also known as the COVID-19 virus. These trends would shape Malaysia’s cyber landscape and impact the efficacy of external engagements.

During the first of the MCO’s six phases, Malaysia’s Department of Statistics survey reported a majority of employees shifted to work-from-home arrangements. In the second phase to the fourth, around 33.5% of companies and firms surveyed reported work from home measures, with 12.3% of the 4,094 firms interviewed recorded a source of income from online sales or services. In comparison, more than 60% of firms reported a lack of income during the MCO period.

This, coupled with observations from the decline of Malaysia’s economy from a growth of 3.9% in the last quarter of 2019 to 0.7% in the first quarter of 2020, had the Malaysian Economic Statistics Review state that resilience of the economy resides in embracing technological advances such as the Industrial Revolution 4.0 (4IR) processes and the digitalisation of the business ecosystem. Such measures for high technology and automating front and back-end business processes could withstand shocks to high reliance on low-skilled foreign workers and inculcate flexibility for business operations, respectively. Thus, among the measures introduced by the short-term Economic Recovery Plan (PENJANA), is the collective allocation of RM75 million aimed for gig economy job security, digital technology transformation, SME capacity building programme and the reskilling and upskilling for Malaysians to serve international clients while working from home.

However, the adoption of technology is impacted by infrastructure issues, the search and match of talent to jobs and a resistance to change. For the business community, the director of business digital adoption in Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC), Muhundhan Kamarupullai, notes that digital adoption thus far is limited to e-commerce activities and video conferencing. The usage of technology or digital applications to automate or analyse data is less incorporated by businesses. Infrastructure, in particular, is hailed as a key enabler in this space with increasing the speed and bridging the rural-urban gap being an area of concern. While the National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan has the goal of an average speed of 30Mbps in 98% broadband coverage by 2023, in early 2020, MCMC shared that fixed-broadband subscriptions consisted only of 9.3% of the population. Notably, a higher number of subscriptions were recorded for mobile penetration rates (118.1%) (Ibid). The light in the horizon comes with the optimism for 5G to be a catalyst of growth. So far in early 2020, Malaysia recorded 100 use cases in 5G across industries such as agriculture, digital healthcare, manufacturing and smart city projects. While delays could be expected, the deployment of 5G will be carried out on schedule, which will begin in the third quarter of 2020.

The pandemic also hastened developments to digitise healthcare. During Malaysia’s battle against COVID-19, Telekom Malaysia Berhad had deployed 5G base stations at two quarantine centres for COVID-19 at Malaysia Agro Exposition Park (MAEPS), Serdang and Health Ministry Training Institute in Sungai Buloh. Microsoft had also streamlined operations and introduced artificial intelligence, machine learning and data management facilities at the MAEPS quarantine center. Meanwhile, a partnership between Huawei Malaysia and the Ministry of Health developed a Cloud AI-assisted diagnosis solution that would reduce the time spent by doctors on CT images. A project in Tunku Azizah Hospital by Skymind Holdings and a Skymind Laboratory of Beurobionix Research in Shanghai China also links local clinical researchers with the research community in China. Digitising healthcare can be seen as the next frontier for medicine as assistance in diagnosis and doctors not restricted by borders can lighten the burden of healthcare workers during or outside times of pandemic. However, the transfer of data abroad and purchase of medicine through e-commerce channels can lack necessary legal protections and quality oversight. Additionally, a developing infrastructure landscape would stall its progress as Telemedicine – particularly those that may involve operating rooms – may require the strength and connectivity of 5G.

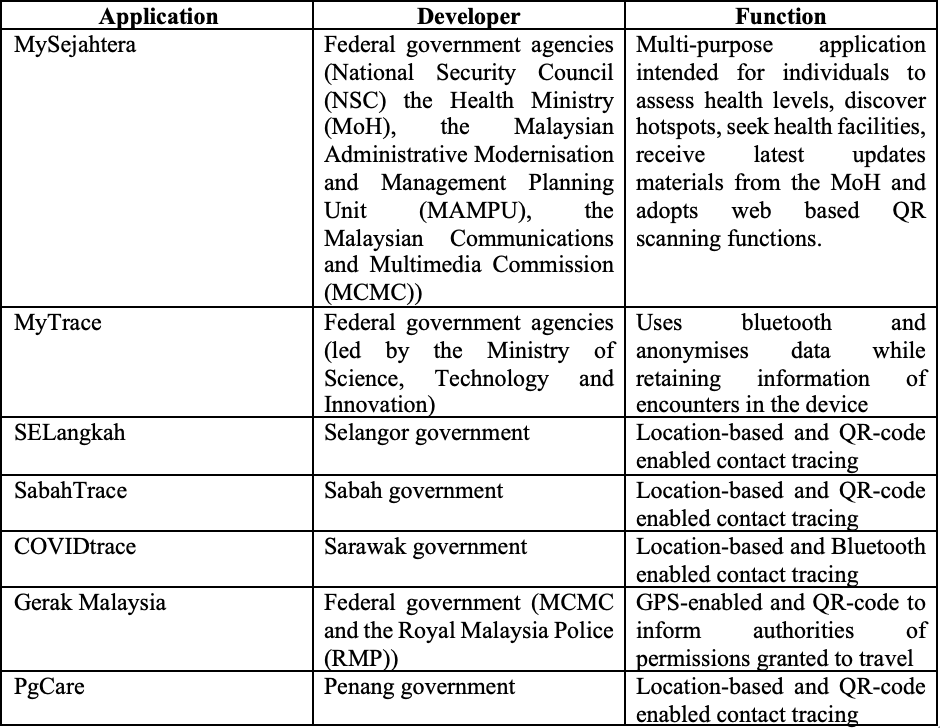

While MySejahtera was made mandatory for all businesses in Malaysia from August 3, 2020, this would not indicate a homogenous contact tracing application market. The pandemic demonstrated the strengths of states as the East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, along with Selangor, Terengganu, Johor and Penang developed their own contact tracing application to add to those produced by ministries.

Table 1: A table showing contact tracing applications in various Malaysian states. Table by author

The applications would defer in terms of methodology, privacy thresholds and where declared, data retention limits. In terms of methodology, applications that conduct contact tracing by anchoring data in locations are such as MySejahtera, SELangkah and SabahTrace where premises would carry a QR code provided by the developers. Alternatively, contact tracing can be conducted by building the network from mobile phone proximity using bluetooth which was a model pursued by MyTrace and is also a component of COVIDtrace. Gerak Malaysia uses GPS tracking for travellers who embark on interstate travel though its usage is reduced when interstate travel was banned. However, the diversity and multitude of application would display weaknesses in regulation within government agencies.

The vulnerabilities can be exemplified by the different privacy practices of the applications. MyTrace, whose development was led by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, uses Bluetooth and anonymises data while retaining information of encounters in the device. Sarawak’s COVIDTrace too states that data would be anonymised and geolocation data would not be collected. The information gathered by COVIDTrace, Selangor’s SELangkah and Sabah’s SabahTrace include the individual’s name, phone number, date and time of the visit to a premise with SabahTrace collecting information on the body temperature. MySejahtera is among the examples of centralised data collection where data in transit is stated to be encrypted. The data security and governance of MySejahtera is managed by the National Cyber Security Agency (NACSA) under the National Security Council (NSC). Data retention limits, where mentioned, range from 21 days to six months. MyTrace stated the retention of data in devices for 21 days while MySejahtera’s check-in feature withholds data for 90 days. Gerak Malaysia stated information on travel would be retained six months after the MCO ceases. In addition, COVIDTrace stated that should users revoke consent, their data would be deleted from the system thus protecting users from future issues of data breaches.

However, the August 3 announcement mandating the necessary download and registration of business owners and operators on the MySejahtera application, indicate the possibility of convergence in application to a centralised data collecting system. MySejahtera is currently the only application tied to the short term economic plan (PENJANA) benefits and as of August 10, MySejahtera received 13,284,611 downloads – equivalent to 60 percent of mobile phones in Malaysia. Certain states such as Penang had announced phasing out PgCARE in favour of MySejahtera after the August 3 announcement. In addition to the check-in feature, MySejahtera’s current form also includes self-health assessments, hotspot trackers, health facilities and news on COVID-19. Future iterations of the application may include social policing features where violations can be photographed and submitted through the application as well as user-friendly features for people with disabilities.

A concern from the proliferation of contact tracing applications are on the positive trajectory of surveillance. The definition of surveillance under the Malaysia Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 (Diseases Act 1988) Section 7 (b) authorises “an officer who finds or has reason to believe that any person is infected or is a contact, may place the person under surveillance until such time the disease is no longer communicable to others” with the power to make regulations stated in Section 31 inclusive of “the collection and transmission of epidemiological and health information and the compulsory reporting of infectious diseases”.

The efficacy of contact tracing application or data collection is balanced against concerns for privacy. How much might be too much data collection? And would the ends justify the means?

Ipsos, a marketing research and consulting firm based in Paris ran a survey in Malaysia in the years 2018 and 2019 where findings indicated a high level of trust in government for data collection. In addition, the 2019 survey indicated that Malaysians (64% of those interviewed) do favour privacy but would consider trading personal data for compensation. As such, the Ministry of Health recorded 700,000 registrations on the MySejahtera application following an announcement of E-wallet credits for individuals installing the application. Additionally, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Mohd Redzuan Md Yusof stated that the government had detected 322 COVID-19 patients using MySejahtera, equivalent to 3.4% of the total cases recorded on August 18, 2020. However, the figure was not specified to determine if these are the mandatory downloads for persons under investigation – and those linked to PUIs – or voluntary downloads from the general community.

While information collection can be viewed as a necessity in the midst of a pandemic, the loss of privacy should not be exacerbated by issues in security. The data management in applications is a sliver of insight to Malaysia’s strength and weaknesses in cyber. While Malaysia has the Personal Data Protection Act 2010, the act was crafted to regulate the private sector and is not applicable to government and state bodies. Thus the PDPA would not be effective at holding the government accountable should there be a breach or misuse of data though Section 203A of the Penal Code provides penalties towards any person who leaks information in the performance of their duties, thus are among those considered to be the legislation apparatus safeguarding the data collection activities conducted by the government to mitigate COVID-19.

Despite that, even for the purpose of regulating the private sector, the PDPA may fall short of safeguards as guarantees to respond to requests for information on data usage and mandatory reporting of a data breach are not covered by the 2010 law. As technology advances, the transparency, checks and balances, as well as well-worded legislation, is needed to secure Malaysia’s cyberspace. Additionally, a thorough data policy that could inculcate and encourage data collection best practices would be useful. Conversations in Malaysia can expand to discuss the merits and detractor to various data collecting practices such as the anonymisation, encryption and concepts such as the ‘right to forget’. These should be further enforced and updated in a cybersecurity strategy that builds on Malaysia’s National Cybersecurity Policy launched in 2008. Crucial updates from 2008 are needed in areas of enforcement, direction to address emerging technology, strategy for international cooperation and navigating tech-related power competition and whole-of-society participation in protecting cyberspace.

These high standards are needed as Malaysia seeks to grow the economy through activities that either contribute to or hinges on data transferring across borders. As the pandemic coincided with greater protraction of US-China trade issues, efforts to attract foreign ICT companies resulted in investments worth RM8.36 billion in 28 projects of which 10 are Chinese companies while two are Japanese companies. However, cooperation in areas such as 4IR, AI, fintech and digital industries would require Malaysia to improve the environment enabling digital economy by addressing gaps in the legislation, solve infrastructure and connectivity issues as well as introduce high cybersecurity standards. With these, Malaysia can project to the world the ecosystem of trust that would build confidence and propel Malaysia to a fully digital future.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.