“The absence of a culture of policy continuity in a governmental change in Malaysia and several other ASEAN member states can be a significant limitation for regional environmental resilience”, writes Dr Helena Varkkey (Department of International and Strategic Studies, University of Malaya)

_______________________________________________

Under the ASEAN Social-Cultural Community (ASCC) Blueprint 2025, resilience has been identified as an essential aspect of human security and sustainable environment. To this end, ASEAN leaders in 2015 committed “to forge a more resilient future by reducing existing disaster and climate-related risks, preventing the generation of new risks and adapting to a changing climate through the implementation of economic, social, cultural, physical, and environmental measures which address exposure and vulnerability”. Through these efforts, it is envisioned that ASEAN should be a resilient community with enhanced capacity and capability to adapt and respond to social and economic vulnerabilities, disasters, climate change as well as emerging threats, and challenges by 2025.

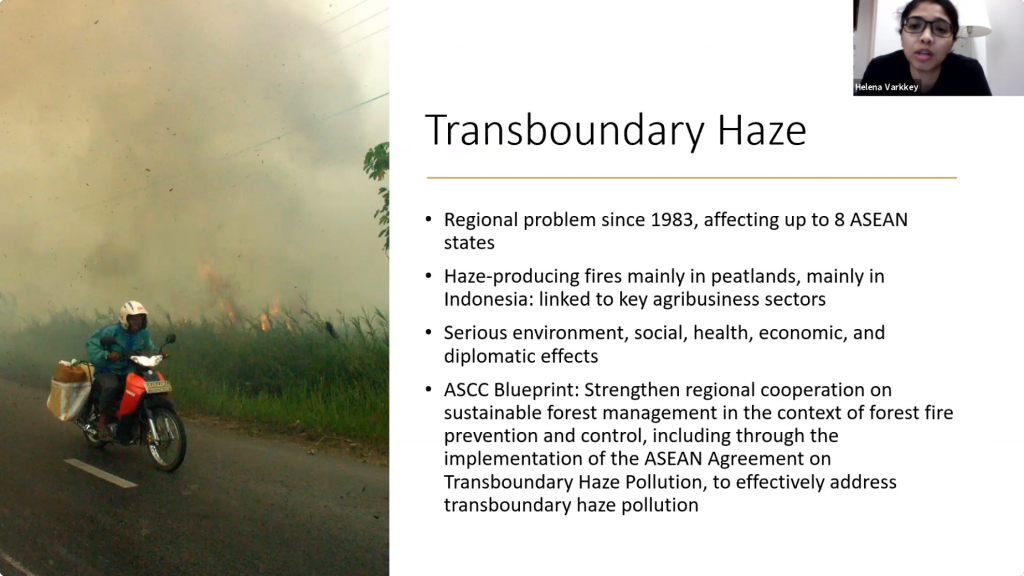

One priority area identified under the ASCC Blueprint is transboundary haze. Transboundary haze has been an ongoing regional air pollution problem since 1983 and can affect up to eight Southeast Asian countries. Haze-producing fires originate mainly from peatlands, mostly in Indonesia, and has been linked to land clearing activities of key agribusiness sectors. These almost annual haze incidences have serious effects on the environment, economy, health and society, and even diplomatic relations between ASEAN member states. The Blueprint outlines the need to “strengthen regional cooperation on sustainable forest management in the context of forest fire prevention and control, including through the implementation of the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution, to effectively address transboundary haze pollution”.

Resilience against transboundary haze has generally been discussed in the context of different segments of society’s responses to haze. For example, the corporate community has developed strategies to maintain business continuity amidst haze, including insurance policies and supply chain adjustments. In addition, various civil society-led initiatives around the region include free car rides and free masks to reduce haze exposure among the most vulnerable. However, peatlands, in which more of these fires occur, are extremely un-resilient: these valuable carbon sinks take thousands of years to form, and once drained, disturbed, or burned, is extremely difficult to rehabilitate and restore ecosystem services here. Because of this, good governance of these sensitive peatlands is extremely important in making Southeast Asia more resilient against haze.

Transboundary Haze Governance in Southeast Asia

While transboundary haze governance has been a priority issue at the ASEAN level since at least 1985, the persistence of haze indicates that these efforts have been less than effective. Scholars have linked this ineffectiveness to the limitation of the ASEAN Way of diplomatic engagement, which includes non-interference over domestic issues, non-legalistic approaches, and a prioritisation of regional economic advancement. A notable outcome of ASEAN-level cooperation over haze is the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution (AATHP), which came into force in 2003. While this agreement reflected the gravity of the haze situation as one of the first legally binding agreements in ASEAN, the spectre of the ASEAN Way was visible in its lack of enforcement mechanisms, extensive procedures for foreign assistance, and limited information sharing mechanisms. Furthermore, ASEAN was unable to overcome frequent diplomatic impasses over haze stemming from mutual finger-pointing between countries involved.

One of the notable elements of the AATHP is Article 4(3), which obliges states to take legislative measures to implement their obligations under the agreement. This Article has been a continual point of contention as it has been interpreted differently by different members. In 2014, Singapore brought into force an extra-territorial Transboundary Haze Pollution Act (STHPA) that would hold accountable any entity which was found responsible for causing haze in Singapore. However, this move was heavily criticised by Indonesia who viewed this as Singapore stepping beyond its own jurisdictional boundaries, and thus not in line with the ASEAN Way. Singapore defended its position arguing that such an act plays an important deterrence role, especially in checking land use practises of powerful agribusiness companies.

Haze Governance in Times of Change: A Malaysian Perspective

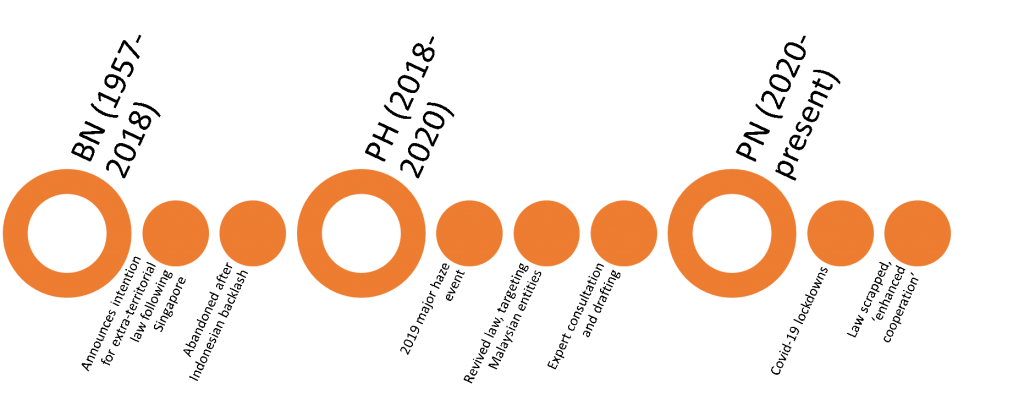

Recent developments in Malaysia in response to this Article will illustrate the importance of resilience in environmental governance. Like Singapore, Malaysia has a long history of single-party rule, with Barisan Nasional at the helm of the government since the country’s independence in 1957. However, more recently, Malaysia has experienced several successive changes of government in a relatively short time span of three years; firstly in 2018 which put Pakatan Harapan (PH) in charge, and in early 2020 which propelled Perikatan Nasional (PN) to power. These changes have coincided with a major regional haze event in 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

In the months following Singapore’s announcement of their STHPA, Malaysia announced its intention of developing a similar legal instrument. However, the ensuing diplomatic spat between Singapore and Indonesia led to Malaysia abandoning these plans. With the change of leadership and the severe haze episode in 2019, this legal instrument was revived under the newly established Ministry of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment, and Climate Change (MESTECC). To reduce diplomatic tension, the draft law was refocused to hold only Malaysian entities operating in Indonesia liable. Drafting proceeded quickly with expert consultation and town hall meetings. However, the second change of government in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic led to the dissolution of MESTECC and the announcement by the new Ministry of Environment and Water (KASA) that plans for the law has been scrapped, in favour of “enhanced cooperation” with Indonesia and ASEAN over haze.

One of the major challenges in the democratic process of governmental change is ensuring policy continuity. While both the PH and PN governments released announced policy strategies focusing on the theme “continuity in change” soon after coming to power, specifics on the environment and transboundary haze in particular was absent from these strategies. Continuity in policy and governance is especially important for environmental resilience, especially in the context of haze where the negative effects of environmental change are especially hard to reverse. However, as seen in this Malaysian case study, there has not only been a lack in continuity in governmental structure (with the continuous restructuring of Ministries and their scope), but also in specific governance approaches to haze at both the national and regional level.

This development has been a missed opportunity on at least two counts: to further operationalise vague legalistic procedures under the AATHP, and to clarify the jurisdictional ‘grey area’ of Malaysian companies operating in Indonesia, which has been at the root of many diplomatic impasses. As a result, ASEAN haze engagement is set to continue in a non-legalistic manner, with peatland governance remaining with, and highly dependent on, national interests of the home country, both of which have only had limited effectiveness in mitigating haze for decades. This higher-level policy uncertainty furthermore sends a weak message for local peatland and fire governance efforts.

The absence of a culture of policy continuity in governmental change in Malaysia and several other ASEAN member states can be a significant limitation for regional environmental resilience. Announced transition strategies are often vague and piecemeal; for example, the new KASA Minister announced that “all the good initiatives introduced during the Pakatan Harapan administration will be continued in the [new] Environment Ministry”, without further clarification. As Southeast Asian societies demand more democratic processes and representation, member states should equally embrace this development and operationalise transition strategies to maintain policy continuity for eventual changes of leadership. Such a pragmatic approach to leadership will help further ASCC’s vision for a more resilient community with sustained, effective responses to environmental vulnerabilities and disasters in the future.

* This post is based on Dr Helena Varkkey’s roundtable intervention delivered on 30th October 2020 as part of SEAC Southeast Asia Week 2020. You can access a recording of the “Environmental Resilience and Southeast Asia” roundtable here.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

1 Comments