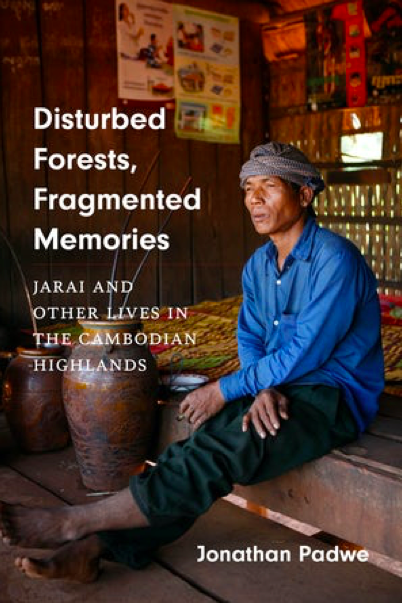

Disturbed Forests, Fragmented Memories is a fresh take of major political events in Cambodia from an ecological lens. Reading this book feels like following the author to meet the Jarai, seeing and observing their lives in Tang Kadon. As a reader, we will obtain glimpses of the past that are very much alive in their stories, writes Ku Nurasyiqin Ku Amir.

_______________________________________________

What do objects from the landscape tell us about the state, history, and society?

In Disturbed Forest, Fragmented Memories, Jonathan Padwe shared his account on the Jarai highlanders tribe in Tang Kadon, a village near Cambodia-Vietnam border. During his study, the author examined the impacts of political events to the landscape which also changes the Jarai’s lifestyle, culture, and history. This book was written based on multiple interviews and oral histories, as an attempt to write history from below or the peoples’ history. The chapters are centred on several events: the aerial bombardment by the United States during Vietnam War, large-scale plantation scheme during Sihanouk’s regime and the Khmerisation project under Pol Pot regime. All these events totally shifted the Jarai’s lifestyle, and their accounts were found in stories of non-human objects.

examined the impacts of political events to the landscape which also changes the Jarai’s lifestyle, culture, and history. This book was written based on multiple interviews and oral histories, as an attempt to write history from below or the peoples’ history. The chapters are centred on several events: the aerial bombardment by the United States during Vietnam War, large-scale plantation scheme during Sihanouk’s regime and the Khmerisation project under Pol Pot regime. All these events totally shifted the Jarai’s lifestyle, and their accounts were found in stories of non-human objects.

The Jarai tribe is a minority in Cambodia and practices set of customs that are distinct from the Khmer people. For example, the Khmer people lived in singular houses, while the Jarai live in longhouses. The Jarai are largely involved in agriculture sector, aside from swidden farming they also foraged in the forest area. This made their connection to nature almost symbiotic, to the point that the plants and landscapes add meaning to their lives. Subsequently, their lifestyle was organised according to the annual agriculture cycle.

I found it interesting that the Jarai does not directly speak about the significant events that impacted their lives, instead they will tell stories about subtle things that are related to it. This makes the role of researcher in finding a cohesion in the stories and connect the dots more challenging. However, it is also understood that events such as the Khmerisation project are sensitive issues as countless lives were murdered in the span of several years. Despite all these challenges, I found the flow and continuity of the book enjoyable.

The main argument by Padwe is that in the course of action by political actors (most of the time the government), there will be impact on the landscape. As a result, the Jarai reacts to these changes, and it can be studied from their stories and association to nature. This can be found in an account about airplane weed, a type of non-native seeds which was said to spread after US bombed the forests. This story is evidence of their sensitivity to changes in the landscape. Even a non-native plant stood out in the forest landscape.

The disturbed forest bears witness to the government actions towards the Jarai tribe and the Cambodian people. Each of these events; the plantation scheme, Khmerisation project and Vietnam War bombings destroyed the native state of the forests. Taking example of the Sihanouk’s regime plantation scheme, although the direct goal of plantations is to gain more wealth, the government also sees the plantation as a way of state-control and surveillance. However, the altered state of the forests was taken as an advantage by the insurgents as bomber planes often spared the plantation areas. Hence, it was more strategic to hide in the plantation, build a camouflage, and remain hidden from the armed forces. At times, the state-imposed schemes worked against the state.

Facing massive changes in the landscape, the Jarai subtly resisted. The subtle resistance is found in the elaboration on how the Jarai adapted with agricultural collectivisation. The contrast between Khmer Rouge’s model of intensive agriculture versus the Jarai’s model of biodiversity puts them in clashing positions. The author argued that the Jarai recuperated to protect their seed biodiversity by exchanging them with other tribes living near the border. This form of agroecological preservation relies on local knowledge of the community which are expanded by practice and experience. In my point of view, the struggle of preservation of local knowledge by the Jarai resembled the movement of peasants-to-peasants in Latin America.

Subtle resistance of the Jarai can also be found in their stories. Going through these changes imposed by the state government, the Jarai experience was translated into smaller forms of stories and descriptions. These fragmented memories are passed down by word of mouth via generations. Thus, it is important that these fragments are written and documented before it is lost, as noted by the author:

‘Landscape from the hills, inscribed on the landscape in often fragmentary form, base themselves in different facts and narrate different perspectives on the region’s past than do histories written by more powerful groups and institutions’ (page 191).

In the future, the work on the Jarai can be expanded by shifting the gender lens. Padwe as a male researcher stated his positionality from earlier on. I agree that the author had to limit his scope to fit this book, but there is only a small section mentioning the role of women in Jarai community which can be expanded by future researchers. In addition, extreme weather events caused by climate change may influence a change of lifestyle among the Jarai. These changes can only be studied longitudinally in a long period of time and may provide us with some insights on how they cope with ecological changes.

In short, the author successfully captured the small voices that lived on within the landscapes. The Jarai is one of the small tribes that constitutes the larger forest ecosystem in Cambodia, hence their local knowledge expanded within the ecology. Understanding the local knowledge is invaluable in this rapidly changing world, as their connections to nature are often dismissed over other forms of technological advancements. This book will be a valuable experience to readers of political ecology, anthropology, and Southeast Asian studies.

______________________________________________

* Banner photo by Bram Wouters on Unsplash

*This book review is published by the LSE Southeast Asia blog and LSE Review of Books blog as part of a collaborative series focusing on timely and important social science books from and about Southeast Asia.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the author alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.