The gig-economy phenomenon in the Global South is quite different from that in the Global North… With limited employment opportunities, alongside the slow recovery after the pandemic, the majority of drivers in Jakarta are full-time workers who may be stuck on a long-term basis in the gig economy, writes Muhammad Yorga Permana

_______________________________________________

When the ride-hailing platforms of Gojek and Grab entered the Jakarta market around 2015, Marhen[1] had been working as a full time employee in a warehouse. Initially, Marhen signed up to drive in Gojek to earn extra income. After returning from work at 5 p.m., he continued to work as a motorbike ride-hailing driver until 9 p.m. Driving for just four hours turned out to be exciting; the earnings were often greater than his salary in the warehouse. In 2017 Marhen’s employment contract was terminated so that he decided to work full-time as a ride-hailing driver until today.

Marhen’s story is similar to most of the ride-hailing drivers I interviewed earlier this year as part of my Ph.D project. Some of them even volunteerily left their jobs in the formal sector because of the attractive earnings offered by the platforms. However, poor working conditions during the time of pandemic made many of them intend to quit the gig economy. A few months before the interview process, in 2021, I distributed a survey to nearly a thousand ride-hailing drivers in Jakarta Metropolitan Area. Two thirds of them revealed that if they could choose, they would prefer traditional 9 to 5 jobs rather than working as ride-hailing drivers.

The regret of being trapped in the gig economy does not just come out of nowhere. I identify three main factors that are related to each other. First, drivers felt that the gig economy does not deliver its promise, especially when the honeymoon phase has ended. Even in 2019 before the pandemic, drivers’ earnings had gradually declined. Unlike at the beginning of its presence, the daily bonus schemes offered by the apps were no longer attractive. To achieve growth as quickly as possible at the early stage, it is common for the multi-side platform companies to burn cash in order to recruit users from both sides of the market. They gave promos to consumers on the one hand and offered attractive incentive schemes to the job providers on the other hand[2]. When the apps had grown and benefited from the network effect, the bonus scheme was gradually lessened so that only a few high-performing drivers could earn it on a daily basis.

The second factor is the significantly growing number of competitors among drivers themselves. In the survey that I conducted, the majority of drivers who are still currently working began joining the platform between 2017 and 2019, a period when the booming of on-demand service in Jakarta reached its peak. Measuring the actual size of workers in the gig economy is quite difficult. However, the ride-hailing driver association claimed that there were one million drivers in Metropolitan Jakarta before the pandemic[3]. I estimate that 450 thousand of them are full-time drivers with an average working hour of 54 hours per week[4]. This is quite different from the trend of gig workers in the Global North where most of them perform gigs as the side jobs. In comparison, the RSA estimates that only 8 percent of gig workers in the United Kingdom work more than 35 hours per week[5].

The gig economy phenomenon in Jakarta, and other cities in the developing world, cannot be separated from the problem of the high informal sector and inadequate opportunities for the formal jobs. At first, the presence of online platforms such as Gojek and Grab were expected to digitalize the conventional motorbike-taxis in the informal sector which were unreliable. However, my survey estimates that 49 percent of motorbike ride-hailing drivers in Jakarta previously worked as employees, while only 5 percent among them previously worked as informal motorbike-taxi drivers. The rest came from student backgrounds, the unemployed, or those from the other low-skilled informal sectors.

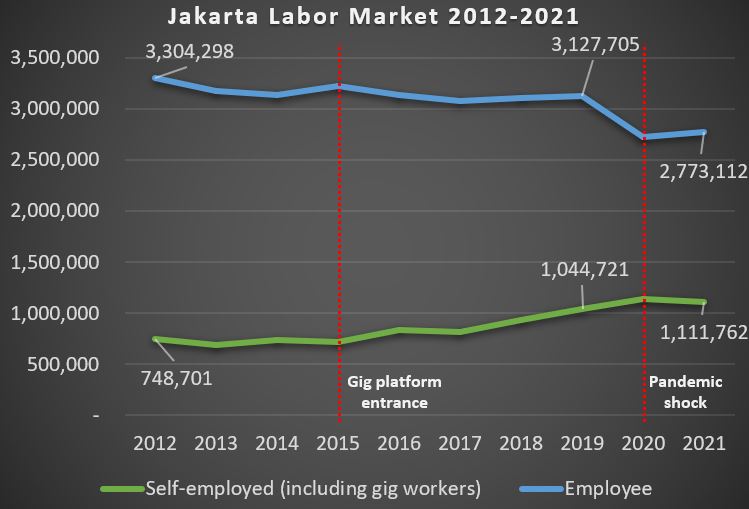

Between 2012 and 2019, formal employment growth in Jakarta was negative (5 percent decline). The presence of gig platforms can be seen as a panacea for those who were previously unemployed and excluded from the formal labor market. Furthermore, those who had previously worked in the formal sector, such as Marhen, were attracted to move to the gig economy when their employment contract no longer renewed. In other word, the labor-oversupply phenomenon in the gig economy might be the direct result of the limited number of good job opportunities.

The third factor is the economic shock of the pandemic. Transportation was one of the most affected sectors due to the mobility restriction policy and the threat of Covid-19 exposure. Actually, the business model of ride-hailing drivers in Indonesia is somewhat different from the ordinary Uber. In the Grab and Gojek applications, a motorbike-taxi driver is not only able to ride passengers, but can also act as a courier and provide food delivery service. During the pandemic, they could survive by performing delivery tasks from restaurants and e-commerce. Still, the insufficient demand and the excess number of drivers made 91 percent of gig workers experience a significant decrease in earnings during the pandemic. A driver said that his earnings were down 50 percent compared to pre-pandemic. Sometimes, in one day he only got 1 or 2 tasks even though the app was kept on all the time.

Stuck and difficult to get out

The gig-economy phenomenon in the Global South is quite different from that in the Global North. For example, Barratt et al (2020)[6] revealed that the majority of gig workers in Australia are temporary workers with no long-term commitment, such as students or migrants who are in the transition phase looking for a full-time job. However, the case of Jakarta is different. With limited employment opportunities, alongside the slow recovery after the pandemic, the majority of drivers in Jakarta are full-time workers who may be stuck on a long-term basis in the gig economy.

An ideal pattern of escaping the gig economy trap is the story of Trisno. On the sidelines of his job as a Grab driver, he was able to participate in an undergraduate program for mature students in the field of elementary education. After graduation, he accepted a job offer as a primary school teacher. Now he drives for Grab only for his supplemental income. Trisno claimed that he can quit at any time, but currently he still enjoyed to remain as a gig worker as a side hustle.

However, Trisno is an outlier. Almost all of the ride-hailing drivers I interviewed had no other sources of income. In general, there were two groups that I met. First, a small faction of drivers who are not interested in working as employees in traditional jobs. Although many publications have uncovered the dilemma of flexibility and the indirect control of the platform through the algorithmic management[7], some workers do feel the benefits of such partnership with the platforms. For example, I met a female driver who regularly had to accompany her two children after school and an old man whose physical condition was limited so that he was only able to drive half day. Platforms such as Gojek and Grab help them earn sufficient money without having to work in the formal labor market.

The second one is the larger group of drivers who regret the change and intend to work in standard jobs. They felt stuck in the gig economy but have no other options for exit. This is exacerbated by the platforms’ approach to propose daily incentives and assign tasks to drivers based on their historical performance. It should be noted that the platform is not a neutral marketplace and the algorithmic management does not allocate the jobs randomly. Tasks for the drivers are not only assigned based on the physical proximity to the customer, but also based on whether historically the drivers had a routine schedule, receive good ratings from the customers, and tend to accomplish all of the tasks given by the platforms without being too selective. The winners in the apps are those who consistently work full time beyond the normal working hours. Thus, they do not have time to look for other opportunities to work elsewhere and find other sources of income. Drivers are worried the algorithm will not give them any more tasks and hence lower their potential income in the future.

Despite the feeling of being stuck, some drivers doubted if they would stop working in the gig economy as they have invested heavily in their own working capital, such as mobile phones and motorbikes. My finding is inline with what has been suggested by Maffie (2022)[8]. He posits that platforms companies intentionally lock workers into this job by manipulating drivers to underestimate the costs of working in the gig economy. To some extent, it might lead drivers to believe that they generate more money than they actually do. For them, the idea of exiting from platform work is not as easy as closing the app and searching for other jobs.

Exit strategy: Good gig and good job

Observing the presence of the two groups discussed above, we have to consider two recommendations that can only be pursued by the policy intervention. Gig drivers themselves have a weak bargaining power to speak up collectively. A strand of literature confirms the difficulty of gig workers exerting collective agency to challenge the practice of exploitation. Although it is possible to do so, many collective movements ended up failing and it is difficult to maintain on a long-term basis[9]. In the case of Indonesia, the main problems are the fragmented drivers’ communities at the neighborhood level and the absence of established labor unions in the gig economy[10]. The majority of drivers I met had been involved in large-scale protests but they felt that the collective movement was less impactful. The excess number of drivers has created a free-rider-problem. They found that it would be useless if some drivers participate in large-scale protest and massive boycotts while the others take advantage of it by working normally in the apps.

The first recommendation is to improve the quality of work in the gig economy. Only by doing so can we increase the workers’ wellbeing and reduce their willingness to exit from the gig economy. I agree with Kaleberg and Dunn (2016)[11] that the gig economy is not always bad. For those who were excluded from employment in the formal sector, the flexibility in the gig economy offers alternative opportunities. In the context of Indonesia, one of the most urgent policy issues is to formally regulate the employment relationship between platform companies and the gig workers[12]. Moreover, in addition to ensuring the right to a minimum wage, health protection, and holiday pay for drivers, platfoms must be pushed to freeze the recruitment process or to set a higher barrier for people to register as drivers. In the context of Jakarta, according to my research, Grab is still hiring at scale to increase the pool of drivers during the time of the pandemic without considering the working conditions of the existing drivers who earn insufficient income.

The second proposal is to create more good jobs in the formal sector, as we need to look at the gig economy problem by using a wider lens. Without many options for jobs, the labor oversupply in the gig economy represents the race to the bottom phenomenon. Although drivers recognissed that they had been indirectly exploited, unfairly threated, and significantly underpaid, the vast majority of workers do not have enough power to exit. They are forced to follow the rules of the game, as if the platforms declare: “If you are not happy partnering with us, feel free to step outside. There are still many people out there who want your jobs“. Creating jobs must also be in parallel with the improvement of the quality of human capital. Affirmative policies to encourage the upskilling of low-skilled workers are required so that there will be other Trisnos who have the capability to escape from the gig economy trap and find a better job.

______________________________________________

[1] Marhen and Trisno are pseudonyms based on my interviews with 30 ride-hailing drivers in Jakarta held between February-March 2022.

[2] See for example Iazzolino, G. (2021). ‘Going Karura’: colliding subjectivities and labour struggle in Nairobi’s gig economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211031916

and Wentrup, R., Nakamura, H. R., & Ström, P. (2018). Uberization in Paris–the issue of trust between a digital platform and digital workers. Critical perspectives on international business. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-03-2018-0033.

[3] Kumparan (2020) Ride-hailing association: there are four million driver in Indonesia. Available at: https://kumparan.com/kumparantech/organisasi-ojol-ada-4-juta-driver-ojol-di-indonesia-1tBrZLEXOEI/full

[4] Based on microdata of Indonesia Labor Force Survey August 2019 (SAKERNAS), I proxy gig drivers as self-employment in transportation and logistic sector in which work is supported by the internet.

[5] Balaram, B., Warden, J., & Wallace-Stephens, F. (2017). Good Gigs: A fairer future for the UK’s gig economy. London: RSA. Available at: https://www.thersa.org/reports/good-gigs-a-fairer-future-for-the-uks-gig-economy

[6] Barratt, T., Goods, C., & Veen, A. (2020). ‘I’m my own boss…’: Active intermediation and ‘entrepreneurial’worker agency in the Australian gig-economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(8), 1643-1661. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20914346

[7] See for instance Rosenblat, A., & Stark, L. (2016). Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries: A case study of Uber’s drivers. International journal of communication, 10, 27. Available at https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4892/1739 and Anwar, M. A., & Graham, M. (2021). Between a rock and a hard place: Freedom, flexibility, precarity and vulnerability in the gig economy in Africa. Competition & Change, 25(2), 237-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529420914473

[8] Maffie, M. D. (2022). Becoming a pirate: Independence as an alternative to exit in the gig economy. British Journal of Industrial Relations. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12668

[9] Tassinari, A., & Maccarrone, V. (2020). Riders on the storm: Workplace solidarity among gig economy couriers in Italy and the UK. Work, Employment and Society, 34(1), 35-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017019862954.

[10] Ford, M., & Honan, V. (2019). The limits of mutual aid: Emerging forms of collectivity among app-based transport workers in Indonesia. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(4), 528-548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185619839428.

[11] Kalleberg, A. L., & Dunn, M. (2016). Good jobs, bad jobs in the gig economy. LERA for Libraries, 20(1-2). Available at https://michael-dunn.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ALK-MD.-JQ-in-Gig-Economy.pdf

[12] Izzati, N. R., & Sesunan, M. M. G. ‘Misclassified Partnership’and the Impact of Legal Loophole on Workers. BESTUUR, 10(1), 57-67. Available at https://jurnal.uns.ac.id/bestuur/article/view/62066

______________________________________________

*Cover image Photo by Fasyah Halim on Unsplash

*About the research: This article is based on the author’s PhD’s thesis that was presented in the Global Conference of Economic Geography in Dublin with the support of the LSE Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre PhD Research Support Fund. The research was also received support from The Indonesia Endowment Funds for Education (LPDP) and LSE International Inequalities Institute.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.