The twentieth century does show an increasing convergence upon the nation-state, for whatever contingent reason it may have first emerged. This convergence created set paths and left (at some point) no other option on the table other than nation-states and nationalism for all political revolutionaries and experimenters out there, writes Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz

_______________________________________________

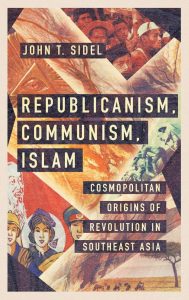

John Sidel’s refreshing synthesis—Republicanism, Communism, Islam: Cosmopolitan Origins of Revolution in Southeast Asia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021)—achieves what so many books in our field of Southeast Asian Studies no longer even aim to do—that is to stitch together the region and to interrogate and contribute to the framing of our region as a region. It also achieves what others of us in the field have long aimed to do, which is to bring our Age of Revolutions into conversation with the global and Western frameworks of the Age of Revolutions.

Our traditional Atlantic framing of the Age of Revolutions begins traditionally in the 18th century and stretches into the early 19th century. This framing allows for a Western account of the diffusion of modernity and the role of revolution in achieving such political modernity to encapsulate Europe and the Americas, including the wave of Latin American Creole revolutions. From there, our next age of revolutions jumps to the 20th century, skipping onwards to the radical modernism of Marxism and the rise of the nation-state as the locus of political legitimacy with mid-20th century anticolonialism and decolonisation. In place of the merely internationalised colony-metropole and Spanish-American War accounts that dominate the historiography, a duly globalised account of the Philippine Revolution stands to connect these two traditional ages of revolutions, connecting the Atlantic and Global South ages in provocative and refreshing ways with import for world history more broadly. This is one of Sidel’s achievements.

Meanwhile, Southeast Asianists have long lamented how poorly the region we study has been incorporated into our frameworks of world history, both in teaching and in research. Sidel shows, here, how powerful a global political model the region has been, particularly in the history of anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggle. This is often why we Southeast Asianists note anecdotally that our field produces an “outsized” number of paradigm-shifting theorists and scholars: Clifford Geertz, James Scott, and Benedict Anderson.

On global histories of national revolution, Sidel asks, “why should we confine our analysis of Southeast Asia’s supposedly self-evidently nationalist revolutions to the boundaries of the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam, the ranks of Filipino, Indonesian, and Vietnamese nationalists, and the indigenous cultures and traditions of these nations-in-the-making?” When I asked that same question with regard to the Philippines, I pointed my gaze Eastward rather than the traditional Westward direction by which we have traditionally internationalised and pluralised the Philippine Revolution’s intellectual foundations. Philippine revolutionary, anti-colonial, and nationalist cosmopolitanism drew crucially and importantly from its constructions of a classical, civilisational understanding of Asia, ecological theorisations of race and the Malay race, which built upon but departed from Ferdinand Blumentritt and other European scholars’ works as well as on the Meiji vision of Asian modernism. Yet, what I sought to do was not to re-occasion a simple reorientation from the West to the East to discover something “internal,” but instead to try to recover wider structures of thought than those that our Eurocentric or imperial gazes in Philippine Studies have missed.

Sidel’s Southeast Asian comparative lens, though different, shares a twin foundation with my own work to return the Philippine Revolution to Asian history and its concepts of Asia and the Malay race. That foundation we share seeks to understand the region within global history and the Philippines within the cosmopolitan region. We also share the goal of trying to efface the boundary that global history can often erect between a local, conservative group thinking about place and nation, on the one hand, and a global, travelling, transnational camp thinking about cosmopolitanism and internationalism, on the other. My book opens with accounts of the presence and the consciousness of the international within such rural Visayan millenarian thinking, rituals, and frameworks, attempting to show the international and global setting in which ideas of social regeneration in the Philippines and Vietnam, in general, occurred at the turn of the twentieth century. While I did not pursue that insight more deeply, Sidel insists on it across all three of his case studies and on every page of his book, and it is a needed corrective.

Indeed, as Sidel himself notes, while the elements of his history of the Philippine Revolution are not fundamentally new, the emphasis and goals of its account are salutary and corrective, and they meaningfully advance the existing history by critiquing the embedded ‘progression’ that remains within Southeast Asian history—that is: national consciousness produces nationalists who make national revolutions. Further, Sidel perceptively identifies and seeks to address the deep explanatory gaps in our account of the revolution: what are the mechanisms and processes by which mobilisation—and then demobilisation—unfolded, linking ilustrados such as Rizal to more modestly educated Manileños such as Bonifacio, provinciano elites such as Aguinaldo and Malvar, and the broader mass of subaltern Filipinos? Second, how can we explain why the Philippine Revolution unfolded so much later than the revolutions of Spanish colonial America, on the one hand, and yet so much earlier than the revolutions in colonial Southeast Asia, on the other? And third, how can we square the striking precocity of the Philippine Revolution in the Southeast Asian context with the notable weakness of subsequent revolutionary mobilisation a half-century later in the heyday of the Indonesian and Vietnamese Revolutions?

In these ways, Sidel’s fresh eye is deeply salutary. He has taken his political and scientific standards for causality and process, not content with the historians’ reliance on mere contingency and thick description, to raise our historical account to a higher standard of explanation, understanding, and precision. Second, his social scientific instinct for comparison not only works to internationalise or globalise our account of these revolutions, as historians have been doing, but also serves to check our understanding and account of the revolution and its processes through international and global comparison. Those are two very distinct things. Both Southeast Asian history and the global history of revolution are richer for Sidel’s sharp critical eye, his subtle historical reading, and his nuanced historical and social scientific argumentation. I will turn now to some of the productive and important questions that reading Sidel’s book raises for me, which I know I will continue to think about for a long time.

While this book incisively dethrones the telos of a colonial state spawning nationalists, followed by revolutions, followed by nation-states, does it replace that telos with another telos of globalisation leading to the nation-state? This is ironic given the work to denationalise, transnationalise, and internationalise each of the three revolutions.

In stitching together bottom-up and top-down approaches to understanding the revolution and seeking to explain why they could begin and did begin alongside how they unfolded and why, the book seems to suggest that cosmopolitan resources, transnational forces (especially economic), and international conjunctures underpin the causal process in the mobilisation, unfolding, and ending of these revolutions. Yet in this dialectical account of transnational economic change, social transformation, and political mobilisation and institutionalisation in the making and the remaking of revolutionary Southeast Asia, are we left with an implied global telos of the nation-state? Is that what increasing global connections, cosmopolitanism, transnational economic logics, and international geopolitics either help or hinder within what is ultimately an arc of history bending, from the 19th century forward, toward the enshrinement of the nation-state as the legitimate political form? That can be argued is an interpretive consequence of Sidel’s narrative.

And, indeed, that is an absolutely valid argument if we want to make it. The twentieth century does show an increasing convergence upon the nation-state, for whatever contingent reason it may have first emerged. This convergence created set paths and left (at some point) no other option on the table other than nation-states and nationalism for all political revolutionaries and experimenters out there. For, despite historians’ commitment to resisting the teleology of the nation-state and to keeping alive the many non-national and supranational alternatives that were attractive and attempted, such a non-teleological historical account works well in individual cases and regional cases but falls apart once taken globally past a certain period. So it is a serious and valid historical argument to make, but I am wondering if it is the one this book seeks to make and how it accounts for the seeming paradox of denationalizing in order to get us back to a global account of the nation-state. I think its commitment to open-endedness is at odds with this outcome. Unfortunately, merely looking at “losers” or interlopers or cosmopolitanism or enabling economic and sociological conditions does not get us out of the teleology of the nation-state in terms of the explanatory forces and synthetic historical account it provides.

Now I want to read an excerpt from the book in order to get us in the frame to think about my final question. Sidel writes:

Revisiting—and retriangulating— of the Vietnamese Revolution from the combined vantage points of Guangzhou, Porto Novo and Antananarivo, and Điện Biên Phủ provides an alternative to the established body of scholarly literature in which Vietnamese nationalism is privileged as the primary ends and means of revolutionary mobilisation…The greater strengths and successes of the Vietnamese Revolution, it is argued, should be understood in light of the specific enabling circumstances provided by Vietnam’s proximity to China and its position both within the full ambit of the French colonial empire and within French colonial Indochina. As in the Philippine and Indonesian archipelagos, the history of the territory today known as Vietnam is one in which commerce and cosmopolitan culture provided the bases for the formation of a succession of states and societies over the centuries up into what historians term the Early Modern Era.

This is important and undoubtedly true and effects a subtle but crucial intervention in the interpretation. Nationalism does not come from indigenous national feeling or national imagining via an intelligentsia alone. It is also made possible, mobilised, and carried by certain sociological conditions, especially economic ones. However, does this not still leave open the definition of nationalism as interpreted through this work? In Sidel’s SEASSI keynote speech on Republicanism, Communism, and Islam, he explained the intervention he was making as correcting the idea that a mass revolution broke out in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam because they were more nationalist than others in the region. Rather, they broke out because they had the sociological conditions for it. So, the Philippine Revolution took place first not due to a greater quantity or force of internal nationalism but because nowhere else were the sociological elements for an 1848-style revolution riper. How, then, should we separate nationalism away from other sociological elements? By this, does he mean a separation between discursive and sociological elements, which will allow us to separate nationalism? I don’t think that’s what he means, however, as important aspects of 1848 were discursive, and he discusses deeply the intellectual origins of each of these societies and their political imaginaries.

So, taking that off the table, if he means to refer to nationalism, instead, as a discrete, historicised phenomenon that comes about in conjunction with certain global historical processes and associated constitutive sociological conditions that allow one to think nationally or to channel one’s desires through nationalist lenses, then isn’t the causal logic of that then incomplete? You don’t have nationalism; you have the sociological elements for it. But what is nationalism? It is premised on having the sociological elements for it. So then, what accounts for whether a nationalist movement and revolution breaks out or not? Perhaps I missed it, or perhaps I misunderstood, or perhaps he has given us still the knotty, meatiest questions left to pursue by having broken this comparative, regional, and global ground for us all.

______________________________________________

*Banner photograph by Ed Robertson on Unsplash

*More information and a video recording of the book launch event for this title, where Dr CuUnjieng Aboitiz spoke, hosted by the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, are available here.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.