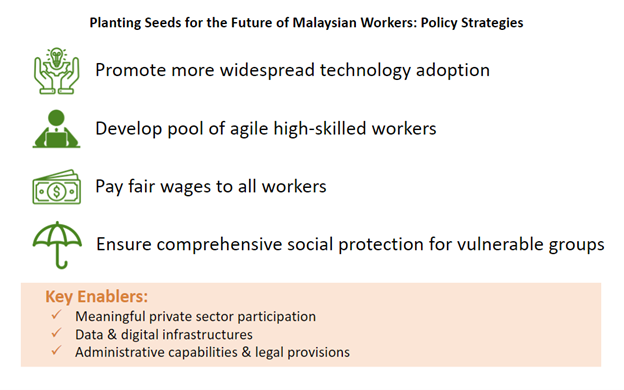

This blog post outlines policy strategies Malaysia can embark on to address long-standing structural issues, as well as to enhance workforce resilience in the face of the ever-evolving demands of the economy. More importantly, we must accelerate policy implementation, evaluate the successes and failures of policies, and leverage evaluation findings to refine and enhance their effectiveness. Prerequisites to push implementation forward should also be in place. To achieve this, a collective, collaborative, and coordinated approach is critical, writes Wen Huei Chang and Qi Cheng Lee

_______________________________________________

Malaysia’s labour market faces several long-standing structural issues. These issues hinder productivity growth and income expansion and skew income distribution. Examples include the prevalence of low-cost production models, insufficient high-skilled jobs, skills mismatches, and low compensation relative to both workers’ productivity and contribution to national income. Additionally, COVID-19 and emerging megatrends have accelerated several shifts with greater challenges. To tackle these structural issues and to improve workforce resilience in the face of ever-evolving demands, there are a few policy strategies that Malaysia can pursue.

Policy Strategy 1: Promote more widespread technology adoption

This policy strategy would help Malaysian firms to transition away from low-cost production models. This entails a move from being primarily dependent on low-skilled, low-wage foreign workers towards producing high-value outputs with greater technology adoption. Foreign workers have supported Malaysia’s economic growth, particularly in sectors where tasks cannot easily be automated. However, in the long term, over-reliance on foreign workers may distort the costs of factors of production, such that it weakens incentives for productivity upgrading and depresses wages. In managing the issue of over-dependence on low-skilled foreign workers, the pivot towards technology adoption can be implemented alongside market-based and progressive demand management tools. These include quotas and multi-tiered levies, which seek to reduce unchecked over-dependence on foreign workers.

However, widespread technology adoption cannot be achieved overnight, as affected industries and workers need time to adjust. As such, implementation can be incremental with a focus on practicality. Critically, technology should be more accessible and affordable. To this end, the Government can provide assistance – particularly to micro, small, and medium enterprises (micro-SMEs) – to be a good partner in their transformation journey from start to finish. Government assistance can include advisory support such as identifying automatable processes, matching firms with technology providers, providing appropriate incentives and financing, and training workers on the ground. Demand from firms is also important to sustain the rate of technology adoption. Hence, it is critical to communicate clearly the long-term benefits of adopting technological processes, such as greater efficiency and quality consistency. These benefits would outweigh short-term transition costs, such as the cost of acquiring machinery and equipment testing and resources dedicated to identifying automatable processes.

Policy Strategy 2: Develop a pool of agile high-skilled workers

To better adapt to future economic demands, the workforce needs to be agile. Reskilling and upskilling are paramount. Given rapidly evolving skills needs and industry demands, lifelong learning is key to enabling workers to pivot. Learning and development should be accessible throughout a working-age individual’s career. On this front, a universal individual-centric training system could empower workers to take charge of their own careers and development. This system would ensure that every working-age individual has access to training courses, even without formal attachments to an employer. This can be complementary to an employer-centric training model, whereby the employer makes training decisions based on business needs. An example of this is the deployment of training levies from the Malaysia’s Human Resource Development Corporation (HRD Corp), which are imposed on firms as a fixed percentage of employees’ salaries.

At the same time, a formal industry-government-academic collaboration is crucial to strengthen the current training ecosystem in Malaysia. The tripartite collaboration between the government, industry and academia to create skills taxonomies and design training curriculum which are relevant and up-to-date has proven to be very effective. For instance, the Penang Skills Development Centre (PSDC) operates on a tripartite model that can be emulated across industries and states. Under this model, the government provides accreditation to training programmes, and funding for selected PSDC initiatives; the industry identifies skills and learning outcomes to guide content of training modules and workshops; finally, academia collaborates with industry to reskill and train prospective workers for subsequent hiring.

The taxonomies and curriculum could be utilised in the individual-centric training system, too – when personalising their training and career roadmap, individuals can refer to these materials to stay mindful of the industry’s current and future demands. Additionally, the tripartite model can facilitate job matching through the creation of on-the-job training courses and apprenticeship programmes in partnership with employers.

On this subject, we must remember that job matching functions through both supply and demand. Therefore, beyond generating more skilled workers, it is also important to increase the demand for such workers. One way this can be done is through attracting quality investments that generate high-value job opportunities. For Malaysia specifically, the National Investments Aspirations (NIAs) outlines guiding principles and desired outcomes for the New Investment Policy (NIP), which include the creation of high-skilled jobs.

Policy Strategy 3: Pay fair wages to all workers

The fraction of national income that goes to workers is smaller than capital owners, despite the relatively higher labour intensity. The introduction of the Productivity-Linked Wage System (PLWS),[1] which aims to establish a closer link between wages and productivity, is a step forward in addressing this imbalance. Under the PLWS, the variable component of a worker’s wage increment is linked to the firm’s and/or worker’s performance. A few adjustments can make it even better. The indicator for performance and the wage-productivity formula must be transparent and agreed upon by both employers and workers.

Furthermore, frequent and consistent reviews must be conducted to ensure that the formula is up to date with industry benchmarks and standards of living. Looking ahead, we could also leverage the living wage as a tool to potentially inform, challenge, and enhance policies related to workers’ income. The living wage allows for a ‘minimum acceptable’ standard of living beyond being able to afford the bare necessities. It should also include the ability to meaningfully participate in society, the opportunity for personal and family development, and freedom from severe financial stress. The living wage should be commensurate with workers’ productivity to avert the risk of a wage-price spiral.

Policy Strategy 4: Ensure comprehensive social protection for vulnerable groups

While we embark on various initiatives to increase workers’ income and build a resilient, future-ready workforce, we must not lose sight of more vulnerable groups in Malaysian society. COVID-19 has brought to the fore the importance of a comprehensive social protection system and Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) to assist those facing severe income shocks. Having experienced and survived the crisis, Malaysia has an opportunity to strengthen its social protection system to ensure future resilience against possible shocks. At the top of the list is consolidation of fragmented programmes to improve access to social protection. Consolidation would also ease the implementation and enforcement of programmes, by reducing the number of agencies involved. The programmes should also have sufficiently granular targeting mechanisms to ensure that proportionate assistance is accorded to households with varying vulnerabilities. Over time, beneficiaries must also be encouraged and empowered to graduate from these programmes, particularly those which involve direct transfer assistance. This would reduce assistance dependency and promote upward social mobility. To facilitate graduation, conditions to receive assistance can cover multiple areas, for example, children’s school attendance and participation in ALMPs such as upskilling and reskilling programmes. Additionally, complementary programmes may act as external enablers for graduation. These could include enrolment in health services and other ALMPs, such as micro-credit for entrepreneurship and the provision of public employment services.

In conclusion, Malaysia has made progress in addressing some of the prevailing structural issues in the labour market, for instance, the introduction of the NIP and NIAs, increased upskilling and reskilling efforts, and the PLWS. However, to face future demands of the economy, more concerted efforts can be undertaken to plant the seeds for a brighter future for our workers. Importantly, the key is to accelerate policy implementation, evaluate the success and gaps of the policies, and enhance policy effectiveness. Most of the policy designs and mechanisms are already in place. What’s left is for us to implement them with greater vigor and gusto.

[1] In Malaysia, around 5.8 million workers (just under half of the number of standard employees in Malaysia) enjoy benefits from the PLWS. While this proportion of the workforce is good, more can be done to expand the beneficiary pool so that gains are better distributed across all Malaysian workers.

______________________________________________

*Banner photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash

*The authors would like to extend their appreciation to Datuk Abdul Rasheed Ghaffour, whose presentation given on 1 June 2023 in the ‘Socio-Economic Futures’ session at the Malaysia Futures Forum, jointly organised by the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre and Khazanah Research Institute was the foundation of this blog.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.