In my MSc dissertation, I examined the association between interethnic contact in national schools, the lack thereof in ethnic-exclusive education institutions, and the extent of homophily in the friendship networks of Malaysian university students. Malaysia offers a unique context to study ethnic relations due to ethnic segregation in education pathways. These findings suggest that friendship formation at the university is affected by experiences in both primary and secondary school, implying that contact effects are enduring, writes Hanson Chong Zhi Zheng

_______________________________________________

Homophily is the tendency for individuals to associate with others who share similar attributes, such as socioeconomic background, values, or interests. This natural inclination has a profound impact on the perpetuation of social inequalities, as economic opportunities and resources may be concentrated within a homogenous network of similar individuals. These effects are exacerbated in countries where the population is divided along ethnic lines coexist within a single political entity. Ethnic homophily in interpersonal relationships implies assortativity by ethnicity in the population, and social inequalities manifest as ethnic disparities. Division and disparities then fuel tensions and precipitate ethnic conflict as different groups contend for control over economic resources and political power. Mediating ethnic relations is a key priority for policymakers in such settings.

In The Nature of Prejudice published in 1954, G. W. Allport argues that contact between different social groups under favourable conditions leads to reduced prejudice and increased acceptance of out-group members. Empirical evaluations of the “Contact Hypothesis,” as Allport’s idea came to be known, focus on the effect of a “contact intervention” on perception towards members of out-groups. National schools provide a unique point of convergence in the life journeys of individuals from various backgrounds. They offer unique opportunities for studying sustained contact between different groups in an ethnically diverse social environment, which has been found to be associated with an increase in the formation of interethnic friendships or an increase in the ethnic diversity of friendships. National schools are also sites for instilling mutual understanding among ethnic groups, which potentially affect the long-term preferences and perceptions of individuals. Studying the individuals who attended public schools in multicultural societies allow investigation into the durability of the contact effect.

Malaysia is a multicultural society consisting of three major ethnic groups, namely Malay, Chinese, and Indian, along with other smaller ethnic minorities. Each of the three major ethnic groups have distinct cultural traditions and history, and each hold onto their respective identities firmly. The majority group, ethnic Malays, view themselves as the indigenous population of the peninsular Malaysia. The Malay culture, the Malay language, and the Islamic faith are the three defining characteristics of the Malay ethnicity. The bulk of Chinese and Indian migration to present-day Malaysia occurred in the 19th century under British colonial rule, which was a period of high demand for labourers in tin mines and sugar and rubber plantations. Chinese and Indian migrants did not assimilate into Malay culture but retained their own separate cultural identities. Many scholars attribute this to the divide-and-rule strategy employed by the colonial administration. Under this policy, British colonisers allowed the traditional Malay ruling class to retain political domination of the indigenous peasant population, while Chinese and Indian migrants were accorded some degree of self-governance.

Intergroup contact during the colonial era was minimal and separate political parties formed to serve the interests of each ethnic group during the negotiations for Malayan independence during the 1950s. During independence in 1957, the Malaysian Federal Constitution became the foundation of the new Federation. It recognises the special position of ethnic Malays and other indigenous populations in the country. The term Bumiputera (translated as “sons of the soil”) was later coined to collectively refer to this special group. The division of the economy along ethnic lines has resulted in economic disparities between ethnic groups even after independence. Ethnic struggle came to define the first decade of Malayan independence, with riots breaking out in 1969. This event has been attributed to longstanding inequalities among ethnic groups. In the aftermath of the riots, a series of affirmation action policies encompassing economics, land ownership, education, and other facets of society were implemented under the New Economic Policy (NEP).

One of the educational goals of the NEP was to increase the proportion of Bumiputera students in tertiary education. This was done through special pre-university institutions that were exclusive to Bumiputera students. It is estimated that 55 percent of university places were allocated to Bumiputera students for a period of 30 years from the implementation of the NEP. Over the same period, demand for higher educated workers rose in rapidly industrialising Malaysia. The limited slots at public universities for Chinese and Indian students meant that they had to attend private universities to obtain tertiary education. Enrolment quotas contributed to ethnic segregation through the displacement of non-Bumiputera students from private universities. Despite the initial NEP aim to reduce ethnic inequalities, ethnic segregation at the university level emerged as Bumiputera students tended to attend public universities while non-Bumiputera students attended private universities.

Ethnic segregation has also endured in the primary and secondary education system in Malaysia, with different education pathways for each ethnic groups as each tend to choose a distinct type of primary and secondary school to attend. At the primary level, there are Chinese and Tamil vernacular primary schools in additional to national primary schools. The medium of instruction in these schools are Mandarin and Tamil respectively. Almost all Chinese parents prefer to send their children to vernacular schools, and more than half of all Indian parents have shown a similar preference. There are also religious schools or Islamic primary schools that cater to the needs of the majority Muslim Malay community. At the secondary level, Chinese Independent Schools provide Chinese-medium secondary education to students utilising a curriculum which incorporates Chinese cultural values and that is distinct from the national curriculum. Additionally, several Bumiputera-only secondary schools were established following the implementation of the NEP. Despite the plethora of options for secondary education, national secondary schools today remain the most common choice for Malaysian students due to their affordability and availability in all states of peninsular Malaysia.

| Primary Schools | |

| Sekolah Kebangsaan (SK) | Translated as “National Schools,” these are national primary schools. There is a total of 5,948 such schools throughout Malaysia, which is one school for roughly 1,345 households. |

| Sekolah Kebangsaan Jenis Cina (SJKC) | These are Chinese vernacular primary schools, where Mandarin is taught in addition to English and Malay. Science and mathematics are taught in Mandarin and English. There is a total of 1,305 SJKCs in Malaysia. |

| Sekolah Kebangsaan Jenis Tamil (SJKT) | These are Tamil vernacular primary schools, where the Tamil language is taught in addition to English and Malay. Science and mathematics are taught in English and the Tamil language. There is a total of 528 SJKTs in Malaysia. |

| Sekolah Agama | Translated as “Religious Schools,” these are schools that incorporate Islamic teachings in the curriculum. They are established and administered by state religious authorities rather than the Ministry of Education. At the primary level, these schools run parallel to the national school system, and many Muslims attend national school in the morning and Sekolah Agama in the afternoons or evenings. |

| Secondary Schools | |

| Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan (SMK) | Translated as “National Secondary School,” these are state schools which most Malaysians attend for secondary education. There is a total of 1,989 SMKs throughout Malaysia. |

| Chinese Independent School (CIS) | These are secondary education institutions that use Mandarin as the medium of language. They do not receive fundings from the Malaysian government and are self-funded or sustained by donations by the Chinese community (Siah et al., 2015). Many were established by Chinese migrants during the 19th and 20th centuries. There is a total of 60 CIS today. |

| Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama (SMKA) | Translated as “Religious Secondary School,” these are established and administered by state religious authorities rather than the Ministry of Education, like Islamic schools at the primary level. There is a total of 61 SMKAs in Malaysia. |

| Maktab Rendah Sains MARA (MRSM) | Translated as “MARA Science Junior College,” these are special boarding schools managed by Majlis Amanah Rakyat (MRSM, or translated as “People’s Trust Council”), which is a government agency formed for the purposes of Bumiputera empowerment. MRSM implements a 90 percent Bumiputera enrolment quota, and its aim is to accelerate the acquisition of science and technology knowledge and skills among the Bumiputera population. |

| Sekolah Berasrama Penuh (SBP) | Translated as “Full Boarding Schools,” these are selective secondary schools modelled after British boarding schools. SBPs were established through the Second Malaysia Plan (1975 – 1980) with the aim of providing quality science and technology education to Malaysian students with high potential. |

Figure 1: Typography of Malaysian Primary and Secondary Education Landscape

I have investigated the relationship between ethnic diversity in the friendship networks of university students and their education pathway, taking advantage of the plethora of options for both primary and secondary education in Malaysia. With the assumption that national schools, which have greater ethnic diversity, offer greater opportunities for intergroup contact, the Contact Hypothesis implies that students who attended national schools will exhibit more positive attitudes towards individuals from a different ethnic group, which is associated with a higher probability of holding interethnic friendships and lower levels of ethnic homophily. I have also tested whether ethnic segregation in the education system amplifies the effects of ethnic homophily. Segregation within schools and the education system as a whole creates an environment where opportunities for meaningful intergroup contact are limited. When students from different ethnic backgrounds are systematically separated into distinct schools, their interactions with peers from other groups become constrained. This separation can reinforce existing homophilic tendencies, and the lack of interethnic interactions can perpetuate in-group biases, which hinder the development of intercultural understanding. The amplification of ethnic homophily in segregated educational settings may hinder the positive intergroup relations and contribute to the persistence of social and cultural divisions.

Using a sample of 203 personal friendship networks of university students with a total of 2,182 friends, I analysed how educational pathway affects with the level of homophily in these networks. Four key findings emerged. These findings offer some empirical evidence to support the effectiveness of national schools in fostering multiculturalism while informing the political debate in Malaysia on the abolition of vernacular schools, where the proponents of abolition claim that these schools are detrimental to nation-building and encourage ethnic segregation.

Firstly, friendships among Malaysian university students are characterised by ethnic homophily. Across all model specifications, a persistent result is that Malaysian university students tend to have friends that are of the same ethnic group as themselves. Being of the same ethnicity is a statistically significant predictor of having a large proportion of friends of a particular ethnicity. across all ethnic groups, two individuals who share a common ethnicity are statistically significantly more likely to become friends. This implies that ethnicity remains a highly salient attribute shaping social interactions in Malaysia and warrants an inquiry into its causes.

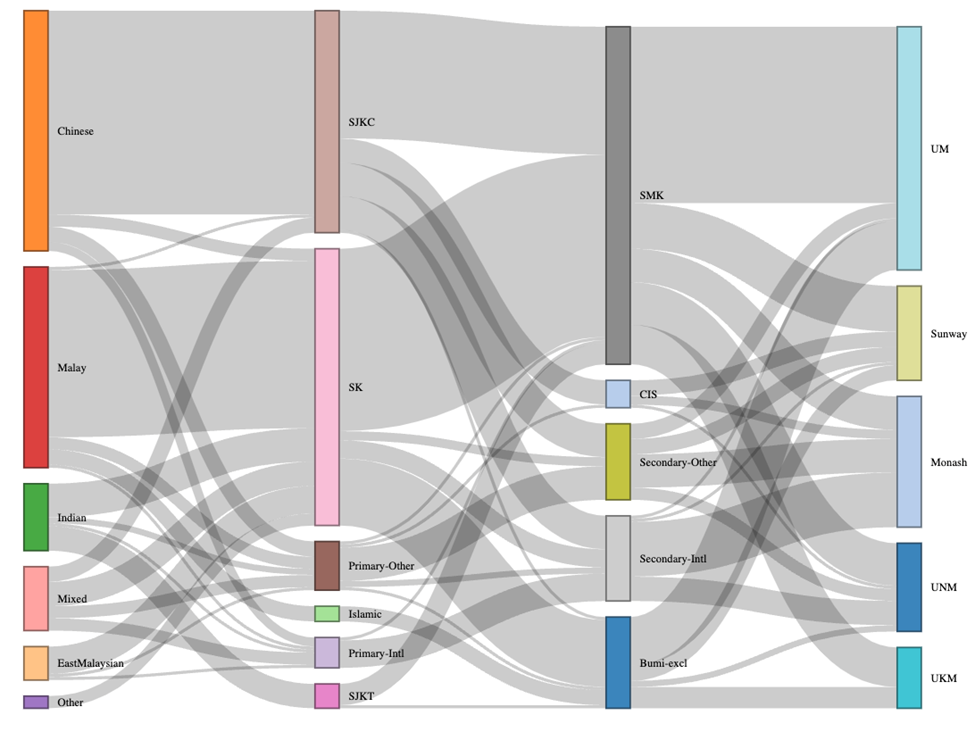

Secondly, the sample shows that the choice of which primary education institution to attend is largely influenced by ethnicity, while the choice of secondary education institution is influenced by both primary education and ethnicity. At the primary level, Malays go to SK, Chinese go to SJKC, and Indians go to SJKT. National secondary schools (SMK) are a key point of convergence for students of all three major ethnicities. A surprising feature of the sample is that a low number of students attend to Chinese Independent School. A few explanations are possible. Since Chinese Independent Schools mostly cater to Chinese students who struggle to follow the curriculum in national secondary schools which is taught in the Malay language, the relatively low number of students in the sample could be because these students pursue tertiary education in Chinese-medium universities, which are not included in the sample. Another explanation is that the United Examinations Certificate, awarded to students who complete their secondary education at a Chinese Independent School, is not recognised by public universities in Malaysia, thus Chinese students opt for SMK instead. The general pattern of ethnic segregation in the Malaysian education system provides a unique context to evaluate how primary and secondary schooling is associated with friendship formation patterns later in life.

Thirdly, I find that students who attend national secondary schools are more likely to have more diverse friendship networks. Among all ethnicities, having attended national secondary school is associated with lower levels of ethnic homophily at the university level. Attending national school is associated with lower levels of ethnic homophily at the university level, implying that intergroup contact increases people to have friends of other ethnic groups. The results are consistent with the predictions of the Contact Hypothesis. There are also several implications about the drivers of friendship formation behaviour. I corroborate the results from previous studies that national schools offer an opportunity to foster interethnic understandings. The results also imply that long-term exposure to contact with other ethnicities can alter the friendship formation patterns of individuals. Experiences in primary and secondary school seem to have lasting effects on the friendship formation patterns later in life. Higher levels of contact with other ethnicities through education in national secondary schools is associated with lower levels of ethnic homophily in university friendship networks. Experiences as far back as primary school can potentially affect friendship formation patterns at the university level, as attending national primary school also has a statistically significant effect on university students’ friendships.

Finally, there is no evidence to suggest that attending ethnic-exclusive education institutions affects friendship formation at the university level. The analysis offers some empirical perspectives on the current political debate on vernacular schools and affirmation action in Malaysia. The operation of vernacular schools is a source of political controversy among Malaysians, with one side favouring the preservation of cultural heritage, while opponents claim that these schools are the cause of ethnic segregation and disharmony in Malaysia. I find no evidence to support the arguments of the critics of vernacular schools. Neither do I find evidence to suggest that attending Bumiputera-exclusive institutions magnify the effects of ethnic homophily at the university level.

Ethnic categorisation is rooted in Malaysia’s colonial history and remains highly relevant as it has been weaponised in the current political arena. Some critics may argue that putting ethnicity in the spotlight in this study perpetuates ethnic categorisation and division; however, progress towards promoting interethnic harmony requires an acknowledgement of these realities rather than ignoring them. A nuanced understanding of the dynamics of friendship formation enables policies to be more effectively designed to promote greater harmony between different social groups. These findings are also relevant to multicultural contexts beyond Malaysia.

______________________________________________

*Banner photo by and copyright of the Author.

*About the research: This blog is based on the Author’s dissertation for his LSE MSc Social Research Methods, for which the Author was awarded SEAC’s Dissertation Fieldwork Grant.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.