In reporting on Inquiry into the Integration of Immigrants in the UK in 2018, the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Social Integration argued that that “the government should … [find] ways to cultivate meaningful social contact between communities”. Yet at a time of deep national divides, it can appear that social cohesion is not high on the political agenda and is even under attack. In such a context, what can we expect for the future? Given tomorrow’s citizens are today’s schoolchildren, their relationships and attitudes to others will be critical.

Published on January 30th, ours is the first national study of schools throughout England to relate inter-ethnic relations to school and local authority ethnic composition. We wanted to find out if experiencing higher shares of those from other ethnic groups affected attitudes and interactions, and whether this differed between school and neighbourhood. We found that school composition was crucial.

Spending time alongside those different from ourselves in school has the potential to shape how we relate to others both in childhood and adulthood. But while we might all hope that greater mixing of people from different ethnicities would be beneficial for social integration, this is by no means certain. For example, influential research showed that more diverse neighbourhoods in the US were associated with a breakdown of trust and cohesion.

We used data from a survey (the England sample of the CILS4EU) matched to data on school ethnic composition. Our sample offers large variation in ethnic composition (for example, from 0% Asian to 40% Asian, from 14% White to 98% White). Our study looks not only at reciprocal majority-minority relationships but also, uniquely, at those between minority groups.

We examined levels of warmth towards those of other ethnic groups and shares of friends for each combination of White British, Asian British and Black British students. We found that having more pupils from another ethnic group in school increased warmth towards that group and friendships with members of that group in almost all cases. In the two cases, where there was no positive relationship between school composition and intergroup relations (White British warmth to Asian British, and Asian British friendships with Black British students), this was because higher shares at the neighbourhood reduced warmth or friendships. Nevertheless, school concentration still balanced out these negative effects.

We also looked at pro-minority attitudes and found that in schools with higher shares of minorities White British students had more positive pro-minority views.

Our research thus showed that schools can provide positive sites for developing better intergroup relations, with even small increases in the opportunities to encounter pupils from other groups. This effect seemed to be particularly important for majority group students. It also shows that even if concerns about lower cohesion in more diverse areas might have some basis, school has the potential to reverse such negative consequences of diversity.

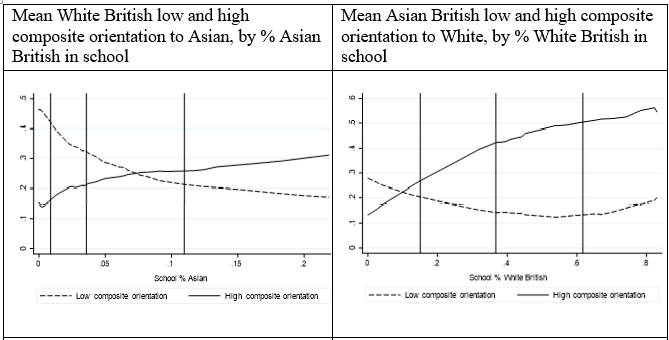

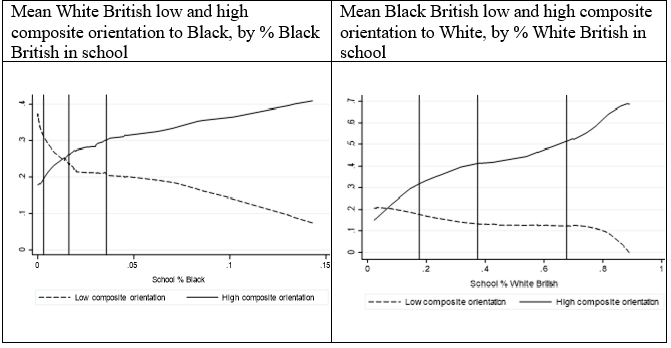

To illustrate our findings, we developed a composite indicator of pupils’ orientation to other groups. This combines the warmth of feeling towards the other group, the number of friends from the other group, and pro/anti-minority views. Using this measure, Figure 1 demonstrates how pupils are much more likely to have a positive orientation toward another group in schools in which that group is more numerous, and much less likely to have a negative orientation.

For example, as a White student encounters more Black students in her school, she is more likely to have a positive view of Black British, and less likely to have a negative view. These are sizeable effects and are true of all the inter-group views.

Figure 1: Inter-group views by school composition

Source: CILS4EU, UK Sample, Wave 1 & NPD. Note: Vertical lines at lower and upper quartile and median. X-axis range is up to 90th percentile of national distribution.

Using these findings, we can show how far increasing encounters between those of other groups in schools can shift these orientations. Consider a hypothetical city with 20% Asian pupils and 80% White. A fully segregated system would imply that Asian students experience 0% White pupils and White pupils experience 0% Asian students. Our results suggest that that situation would yield the result that approximately 47% of Whites would have a low orientation towards Asian pupils and around 30% of Asians would have a reciprocal low orientation; so overall 44% of all pupils in the city would be ill-disposed to the other group. By contrast, in a fully integrated system, overall around 20% of pupils would have low orientations. This halving of the number of pupils with such views in an integrated school system seems valuable. In terms of high orientation, if this city’s schools were fully segregated, only 18% would have high orientations to the other ethnic group, compared to 53% if fully integrated.

Since we show that school ethnic composition is more significant in promoting good intergroup relations than neighbourhood composition, and since it is harder to change people’s choices about where they live and work, the level of ethnic segregation or contact in schools becomes crucial.

The policy question is then how to encourage greater mixing. This is not straightforward. Even within schools of a similar composition there was variation in students’ interethnic orientations, indicating that what schools do also matters. Nevertheless, our paper offers new evidence to support the development of policies that create opportunities and structured contexts for students from different backgrounds to mix. The relevance to a more cohesive future to researching and implementing policies to encourage contact is therefore clear. It may not be easy. But our results now quantify just how valuable that is.

Notes

Burgess, S. and Platt, L. 2020. Inter-ethnic relations of teenagers in England’s schools: the role of school and neighbourhood ethnic composition. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1717937

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.