In April 2020, New York became the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic. For the first time in the city’s history, the 24-hour subway service began to shut down every night to be cleaned and disinfected. With the subway being a popular spot for homeless people to shelter at night, the new measures have led to heightened risks for this population.

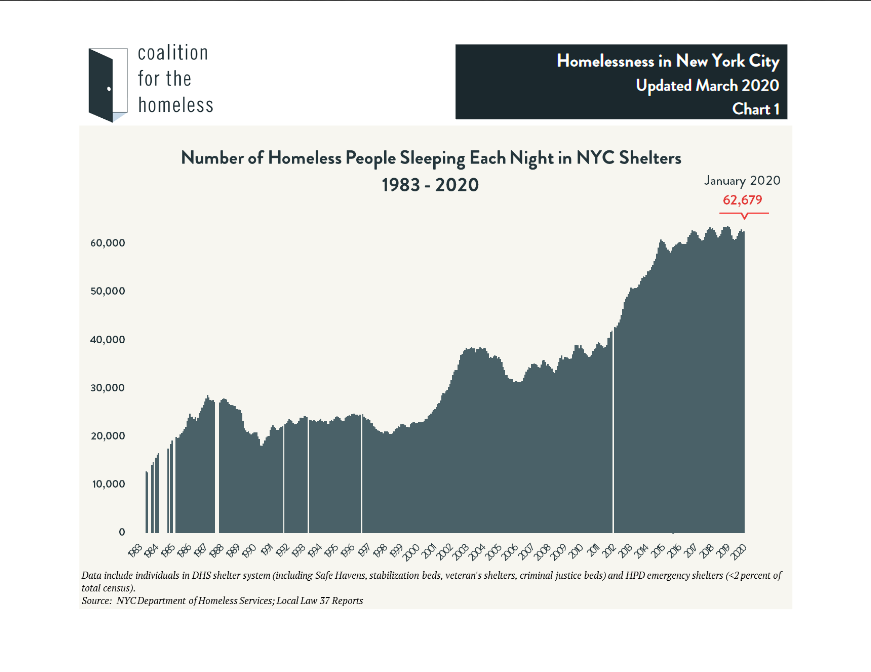

Since the 1980s, the Coalition for the Homeless has recorded a dramatic increase in people using the city’s municipal shelter system (as seen in the graph below). By January 2020, there were already 62,679 people sleeping in the shelters each night. Now, with authorities removing homeless people from trains, the numbers congregating in shelters have soared.

The subway closures are of course primarily an attempt to tackle the spread of the virus. But for some they are also an act of intimidation that sweeps the homeless problem under the rug without addressing the issues behind it. According to the policy director at the Coalition for the Homeless, Giselle Routhier, it encourages a “more punitive approach” that will increase the vulnerability of the homeless population and possibly expose them to the criminal justice system.

Police officers forcibly remove people from the trains each night and then direct them to the municipal shelters. Already risky environments prior to the outbreak, overcrowding in these shelters now means multiple people are sleeping in proximity to one another, while also sharing facilities. What should be a refuge for the homeless in fact turns out to be a haven for the virus. As of May 6th, more than 700 people in shelters had tested positive for COVID-19, and 65 had died.

These inadequate conditions mean many homeless people have refused assistance and chosen to sleep on the streets or night buses. Not only does this transfer the problem elsewhere, but it also exposes homeless people on the streets to further health risks such as drug dependency and street violence. Additionally, with a serious shortage of outreach workers and protective gear, basic hygiene supplies have become limited. This exacerbates the stigma already experienced by this population since they become a ‘health hazard’ to those around them during the pandemic.

For young people and families with children who are homeless, the insecurity, isolation and uncertainty generated by COVID-19 may be particularly harmful. In addition, with recent findings that people of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic background are more likely to die from COVID-19, the homeless population that also intersects with this category is at greater risk of more severe illness. Ethnic minorities who are homeless are also prone to an even further increase in stigma, violence and discrimination on the streets, especially with the narrow-minded assumption that the virus belongs to a certain race (e.g., the “Chinese” virus).

So how can the city’s government better protect the homeless and acknowledge them as part of society? Current policy seems only to heighten the vulnerability of homeless people to COVID-19 and other social issues. Displacing these individuals from one inadequate setting to another merely exacerbates the problems they face, and service providers do not fall under the formal health-care system, meaning there is a lack of funding and attention. Acknowledging and drawing attention to these problems should therefore be the first step.

What is also lacking is an intersectional framework that humanises this population and their diverse experiences. Indeed, intersectional approaches have gained traction in global health recently to better analyse and address the interplay between different vulnerabilities and advantages. In this outbreak, it is possible for the multiple identities in the homeless population to be disregarded (especially those with special circumstances such as disabilities or drug dependencies), which results in their needs not being addressed with the urgency that those with housing may receive. With an intersectional framework in place, a coalition could then begin to fight for proper housing and medical attention.

Policymakers should also invest in understanding the vulnerabilities that intersect in homeless people, and their marginalisation and the challenges they face. It is important that they have the same opportunity to protect themselves during the pandemic as essential workers or anyone else for whom staying at home is not an option. The state government should immediately introduce outdoor hand washing stations in public areas and provide access to public restrooms, as well as material that informs users of how to stay safe. To assist shelters, more should be done to create extra beds so that social distancing is possible. For instance, the conversion of recreation centres and unoccupied hotels into temporary accommodation could provide more space for those in need. Testing kits and the provision of basic information on how to recognise COVID-19 should also be circulated to homeless shelters and outreach workers, along with adequate hygiene supplies.

New York’s homeless population must not be marginalised and pushed into the shadows of society. The COVID-19 pandemic should act as an admonition for New York’s government and policymakers. To improve the situation, they must start recognising this group in society, with all its intersecting identities, and guarantee its members’ rights to safety and adequate shelter.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Image credit:

Thumbnail image: “New York” by morten f is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Banner image: “Hungry” by Jeremy Brooks is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Very educational article on the topic! So well worded? let’s not forget about the homeless people during these uncertain times!

Amazing article in fact. I truly believe Covid-19 has exposed the disparity among the marginalised.

Such a good article! Very well written and informative.