In the short time since George Floyd died during his arrest in Minneapolis, Minnesota, protests against police brutality have spread across the US and the rest of the world. Johann Koehler addresses why protests are back in the spotlight, what they say about US policing, and how they intersect with the response to COVID-19.

Why are we witnessing a resurgence in #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) protests now? Is something distinctive happening?

The past week’s #BLM protests have been remarkable: in the past ten days, people have gathered in all fifty US states and also in solidarity across the world. This level of organization is a rare thing, and its scope eclipses even the initial #BLM protests in the summer of 2014. Clearly something distinctive is happening.

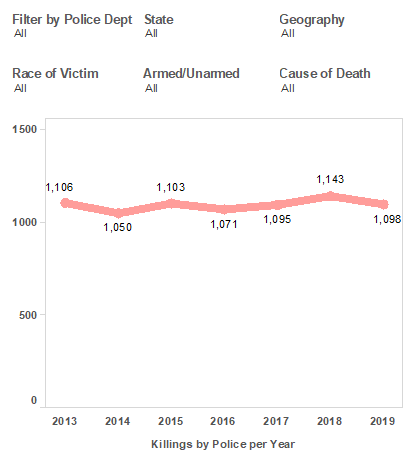

But, so as not to mis-state that distinctiveness, we should differentiate two closely related yet separate developments. The public outrage to which these protests give voice varies much more than the underlying police brutality to which they object. Official data systems that monitor how frequently police kill in the US remain scandalously inadequate, and crowd-sourced databases have proven far superior. Triangulating those crowd-sourced datasets teaches a sobering lesson: cops kill citizens at a fairly stable rate, in the order of almost three people a day (Figure 1). Almost one of those three daily victims is Black—a victimization rate that far outpaces what we observe among comparable groups.

Figure 1 – Killings by US police per year

Source: Mapping Police Violence

Given that police killing has been so constant while public outrage has waxed and waned so erratically, perhaps the question isn’t why is police killing squarely on the agenda now? Maybe the question is instead why hasn’t police killing been on the agenda all along?

What does the response to protests tell us about American policing?

American policing is a fragmented thing. Tens of thousands of police departments strewn across the country’s 50 states defy efforts to identify any one police response to the protests. Footage therefore abounds of strikingly different police responses across America. Where some officials hope to defang the public bite by redirecting sentiment from protest into parade or from dirge to dance; others impulsively rush to arrest whomever they can; others fire tear gas upon citizens irrespective of threat or vulnerability or protection or youth or frailty; there is also a growing recognition that police officers in some jurisdictions have targeted media personnel. Framing the police response as a measured one has therefore become decreasingly tenable.

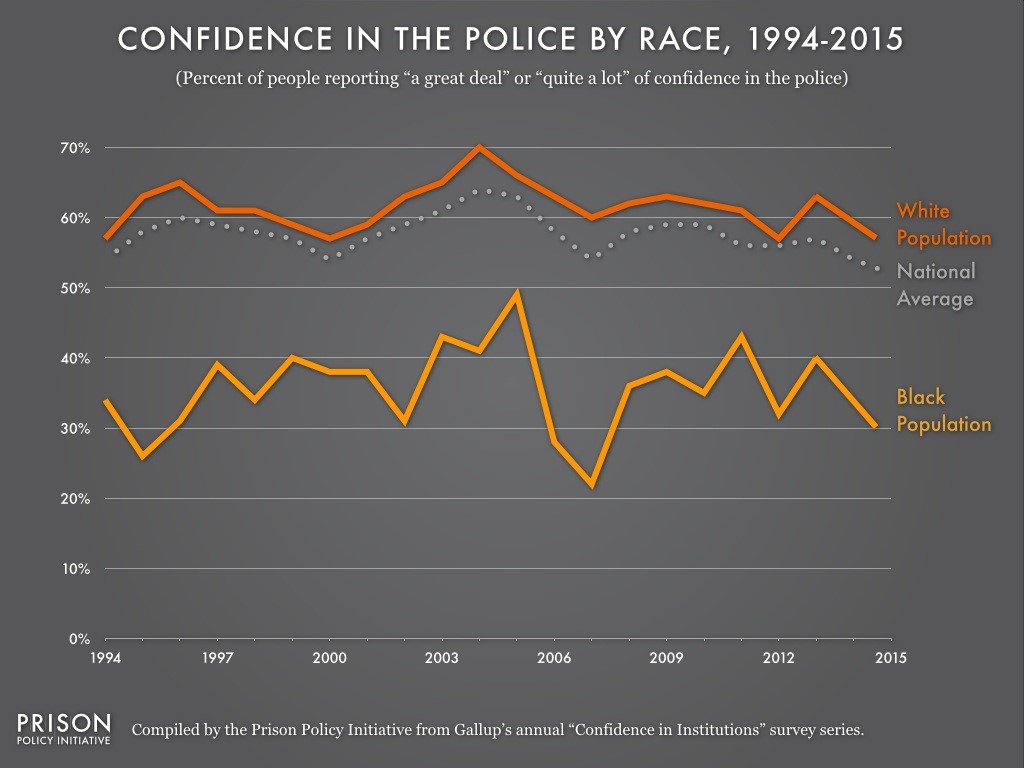

Consequently, there’s been an unshakeable impression that, if indeed anything can be said of ‘American policing’ as a whole, it’s that the institution is losing its grip. As Figure 2 illustrates, Black support for the police in the US has fallen short of the halfway mark for over two and a half decades. Military leaders left and right now denounce President Trump’s bellicose resort to the police as ears for his segregationist dog whistles. And longstanding complaints about the distended resources that American police consume fuel swelling support for drastic cuts to police departments.

Figure 2

Source: Prison Policy Initiative

At last count, the US is home to well over 15,000 law enforcement agencies. American police departments are diffuse, local, small, and unconnected. Wide variation in how those departments respond to protest should therefore come as little surprise. But by the same token, that variation should also sharpen our appreciation of the obstacles that impede #BLM’s ambitions for large-scale reform.

How does the pandemic complicate the protests?

Policing public order is a challenge . Right now, the social and political backdrop is anything but. Hastily-drafted distancing measures that predate the past week’s protests authorised the police in some jurisdictions to enforce curfews to mitigate COVID-19’s spread. Putatively warring hashtags awkwardly pit #FlattenTheCurve against #BlackLivesMatter.

But police brutality is a pressing public health threat, too. Like COVID-19, the costs of police killing distribute unevenly and exact more harms than just the bodies it leaves behind. Measuring which threat is worse or more pressing is hardly straightforward. Deciding how to regulate them is more challenging still.

Even though public health may underpin some police efforts to disperse (even peaceful) protest, public trust for the legitimacy of such dispersals will not be forthcoming. The previous month showed us a neat counterfactual: white, conservative protestors received little police pushback when they brandished attitudes, assault rifles, and rocket launchers while agitating against government over-reach. Compared to the police’s permissiveness in the previous month, even good-faith intervention to quell disquiet or mitigate viral contagion will appear as a bad-faith suppression of legitimate grievance and First Amendment expression.

This blog post was originally posted on the USAPP blog, here.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.