The mainstream approach to reducing the harm from the COVID-19 disease is to mandate or encourage an array of social distancing behaviours. But there is a tension in this approach. Imran Kahn, the Prime Minister of Pakistan, expressed this tension as, “In the subcontinent, with a high rate of poverty, we are faced with the stark choice of having to balance between a lockdown necessary to slow down/prevent the spread of COVID19 & ensuring people don’t die of hunger & our economy doesn’t collapse. So we are walking a tightrope.” In two papers, we unpack that tension, and we show how to walk the tightrope.

The life-saving tension between health and economy

Policies for increasing social distancing generate behaviour changes that have the undesirable effects of reducing GDP, personal incomes, and increasing unemployment leading to calls for opening up the economy and thereby reducing social distancing. Reducing the degree of social distancing makes more sense in developing economies which lack the private and public safety nets to compensate for lost income. Many of the poorest who marginally survive in normal non-pandemic times, may perish in a severe declining developing economy when forced to increase social distancing. — The causes of death would include famine, suicide, and drug abuse.— If opening-up the economy is implemented to reduce these fatal outcomes, we suggest that social distancing be maintained at the level that minimises deaths.

The optimal amount of social distancing minimises deaths. Whether in the Global North or Global South, relaxing social distancing should proceed only if it results in fewer excess deaths, deaths directly caused by COVID-19 plus those deaths indirectly caused by the change in circumstances related to COVID-19. For example, if the number of COVID-19 hospitalisations crowds out pregnant women who would need to go to the hospital for a birth delivery with complications, and the mother and baby die, they are counted as a maternal death and a neonatal death. But they should also be considered excess deaths due to COVID-19, even though neither the mother nor baby was diagnosed with COVID-19.

Owing to the variation across places in how deaths are recorded, excess deaths are difficult to measure. However, they can be inferred by comparing total deaths from all causes above what the number of all deaths would be using trend data from prior years. This would include both deaths from the virus and deaths from decreasing economic activity. Monitoring excess deaths in this way helps plan how we would open up an economy, which is usually done in phases. Economic policy should not proceed to the next phase unless excess deaths have declined.

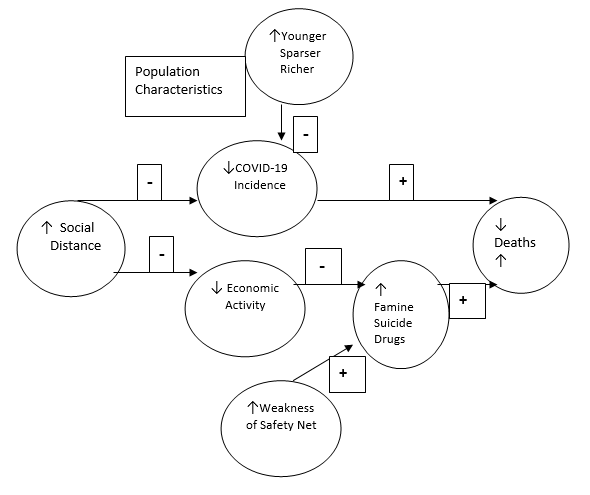

A causal flow chart model illustrates the relationship between social distancing (on the left) and deaths (on the right). The chart traces two opposing forces of social distancing that affect excess deaths: a negative relationship to excess deaths, by reducing the ability of COVID-19 to transmit from person to person, which is the top causal linkage; and a positive relationship to excess deaths, by reducing economic activity of the very poor, which is the causal linkage displayed below.

How do we navigate the tension?

In another paper, we set up the calculus optimisation mathematics for determining how to walk the tightrope to which Imran Khan alluded. We think the death minimisation point for developing countries will occur at a point less than maximum social distancing. It is tricky to accurately measure excess deaths, devise an index of social distancing, and take account of time lags. However, the model can be operationalised by making incremental changes.

From an original position, reduce the degree of social distancing by one index point or increase opening up the economy by one phase level. With a lag of about two weeks, have excess deaths gone down or remained constant? If so, consider decreasing the degree of social distancing and thereby open up the economy even more. If, on the other hand, excess deaths have gone up, the death-increasing effect of less social distancing has been greater than the death reducing effect of a more open economy. Then go back to your original position and consider an opposite move to further increase the degree of social distancing. This should be fine-tuned differently for different places.

The position of the relationship between social distancing and excess deaths is likely different (has shifted) for different places. Across the U.S., for example, places are heterogeneous in demographics, geography, health status, and policy. As of June 17, 2020, according to tracktherecovery.org, daily reported Covid-19 deaths in the U.S. as a whole have been falling since April 15. Yet, according to data from National Public Radio, for the two weeks previous to June 18, twenty-three states show an increase in the percent change in new daily COVID-19 cases. This rate of change is similar to the pattern found in the three-day moving average of cases found on the Johns Hopkins website. Cases are an imperfect measure of the severity of the COVID-19 disease and deaths, but there is likely to be a positive relationship. Those twenty-three states need to promote or mandate more social distancing while the other twenty-seven states can continue to cautiously open up their economies.

Even if the economy opens up more, social distancing practices should keep excess deaths in view as much as possible. By this we mean policies should encourage wearing masks, shopping outside if possible, not going to crowded places, maintaining physical distance from other people, working from home if possible, and washing your hands often. If one must go to work, it is important for employers to provide good quality personal protective equipment and reduce face to face crowding. Of course, this may push costs higher and thereby prices higher, but we consider this worthwhile to save lives. Dealing with COVID-19 has resulted in a decision-making disconnect between comfortable politicians and executives making the policy decisions and those most vulnerable to the disease: Blacks, Hispanics, the elderly, the poor, people with pre-existing chronic health conditions, and those living in congregate facilities.

For developed countries, we suggest that walking the tightrope with COVID-19 on one side and the economy on the other is inappropriate. For example, in OECD member countries, the majority of the populations have access to private and public safety nets, so a major economic disturbance of a few months or a year is not likely result in additional deaths. It is not clear that suicides will increase during the COVID-19 crisis in developed countries but the May 4, 2020 Washington Post reports that calls to a Federal emergency hotline for emotional distress have increased 1000% in April 2020 compared to the same time last year. Full compensation, to the most vulnerable, should be enacted to reimburse them for the harms that accompany social distancing. The federal government should overcome bureaucratic inefficiency and bottlenecks, and increase the amount of transfer payments and services going to the most vulnerable poor. The most vulnerable poor should be guaranteed a safe job, subsidised housing and counselling, or a basic minimum income during and after COVID-19. In developed countries, social distancing should occur to the extent that doing so minimises excess deaths.

It seems reasonable to consider that when social distancing is increasing and income is declining in developing countries, famine, hunger, suicide, substance abuse, domestic abuse, and working in unsafe places will increase and access to health care will decrease. We think these effects are sizeable for developing economies but small or negligible for developed economies. Developed countries have public safety net systems such as unemployment benefits, food subsidies, housing subsidies, and stimulus checks; and private safety net systems such as savings, assets to sell, gifts and loans from family and friends, food banks, religious charities, and credit card loans. However, it is unclear whether some of these safety nets are real or just apparent. An article in the May 15 New York Times reports difficulties in applying for unemployment benefits. That reportage recounts an inability to submit applications and payment delays. Their investigation reveals that more than half of those applying for unemployment benefits were unsuccessful.

Insecurity and psychological pain can occur from discouraging people from going to work and socialising in person. However, few people in advanced economies will starve to death from this, at least in the short term. In the developing world, safety nets are weaker and access to food is scarcer. The World Food Program, an arm of the United Nations, estimates that the number of people in low and middle income countries facing acute food insecurity will rise to 265 million in 2020, up from 130 million in 2019, as a result of the economic impact of COVID-19. This translates into a likely 1.26 million extra people dying in 2020, in middle- and low-income countries, from the economic impact of COVID-19. The reasons for food insecurity in 2019 were the usual causes of hunger: conflict, climate change, and economic crisis. COVID-19 adds to this humanitarian problem the extra loss of income from more unemployment, more illness, more trade barriers, heath care access being crowded out, and a dramatic interruption of the supply chain that provides nourishment to food-insecure people. These poorest of poor in our world, who earn $1.90 a day or less and have little or no savings or other assets to fall back on, are approximately 700 million people in the world.

Our model suggests that it is sensible to set social distancing policy on the basis of mortality both from the virus and from economic decline. The amount of social distancing for a place should be determined by choosing the degree of social distancing that minimises excess deaths.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.